Regia / Director: Mario Monicelli, 1963

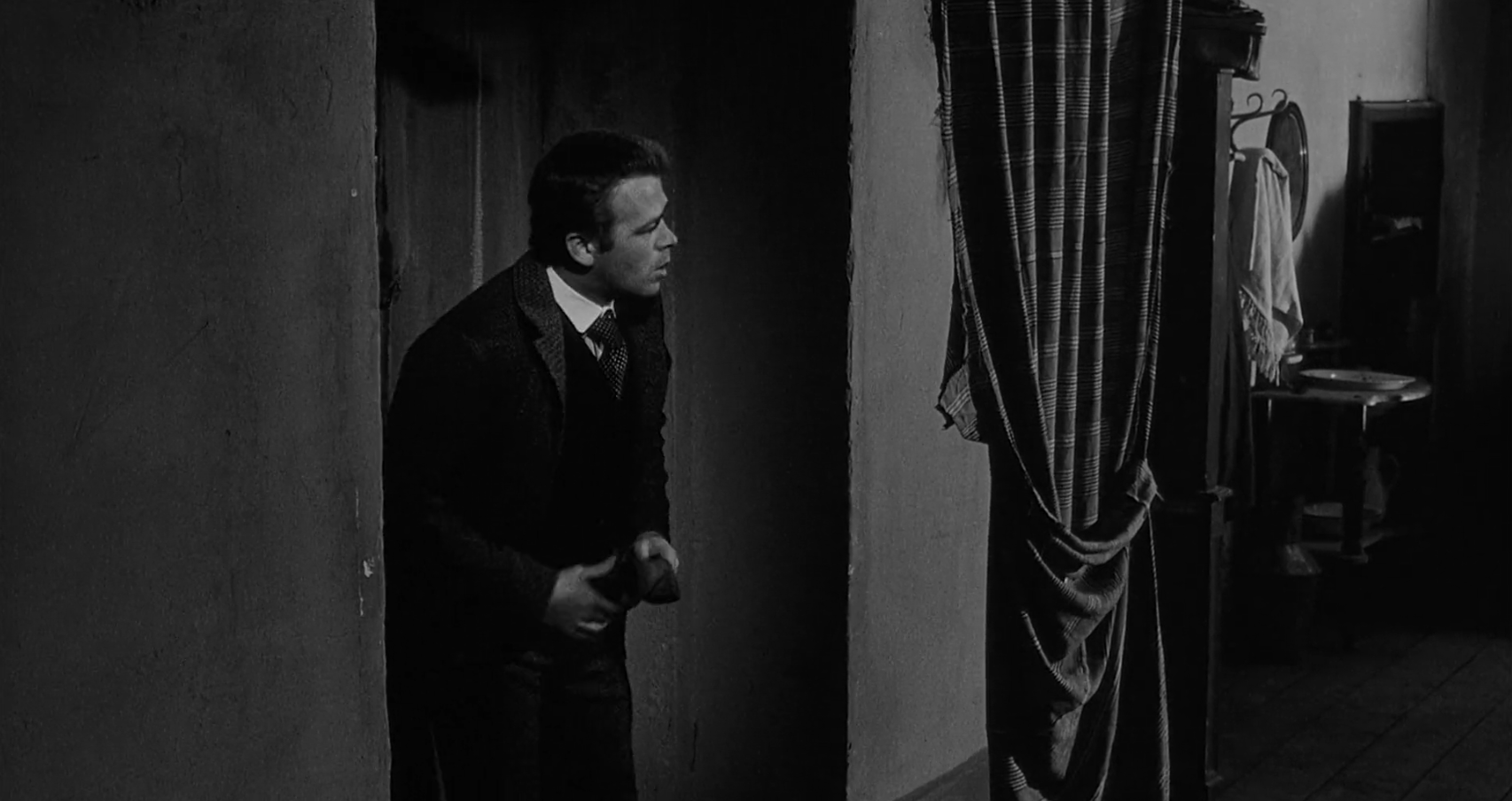

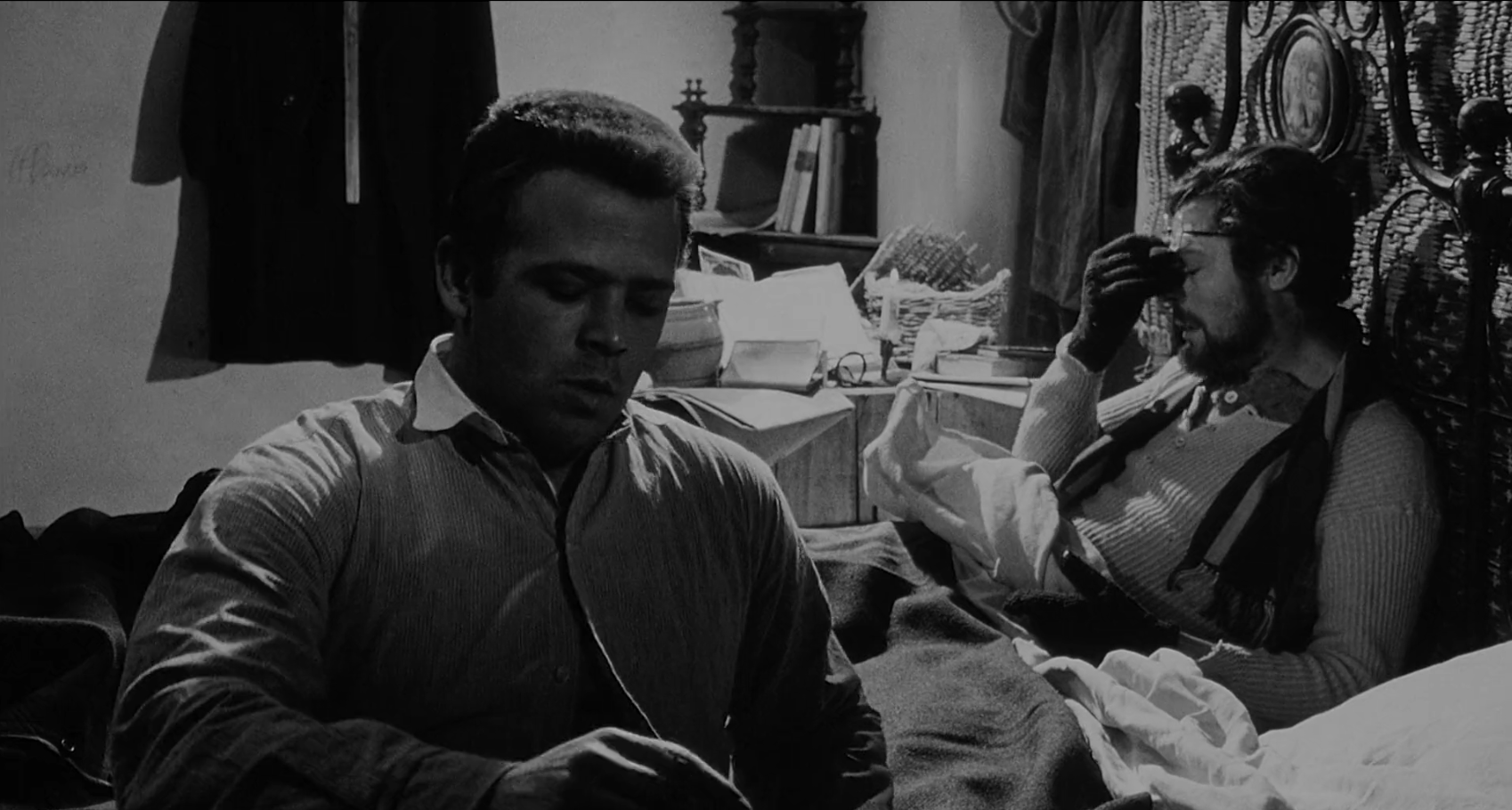

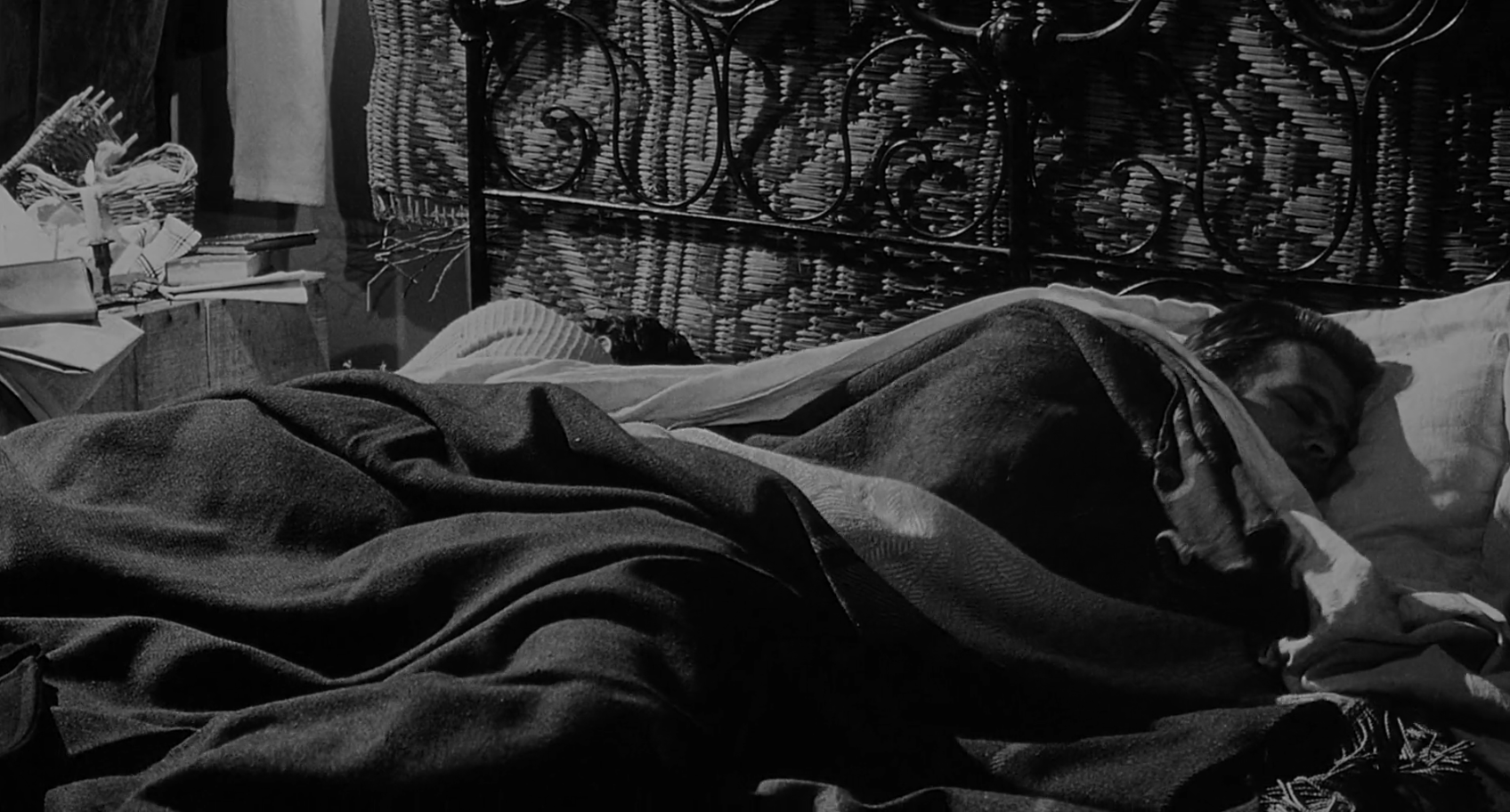

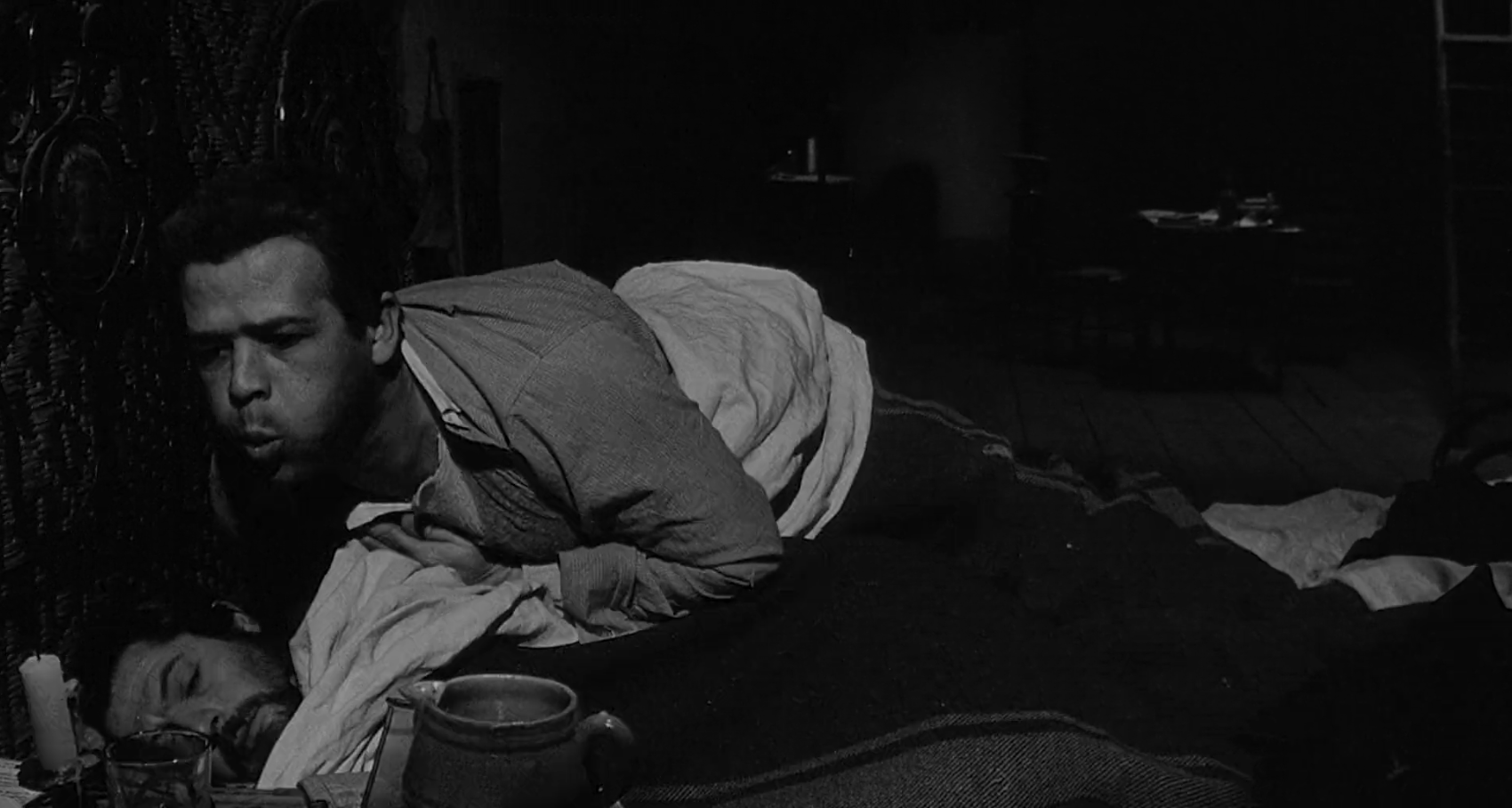

Il professore sta leggendo a letto quando Raoul entra e comincia a discutere con lui, minacciando di picchiarlo.

The Professor is reading in bed when Raoul comes in and starts arguing with him, threatening to beat him up.

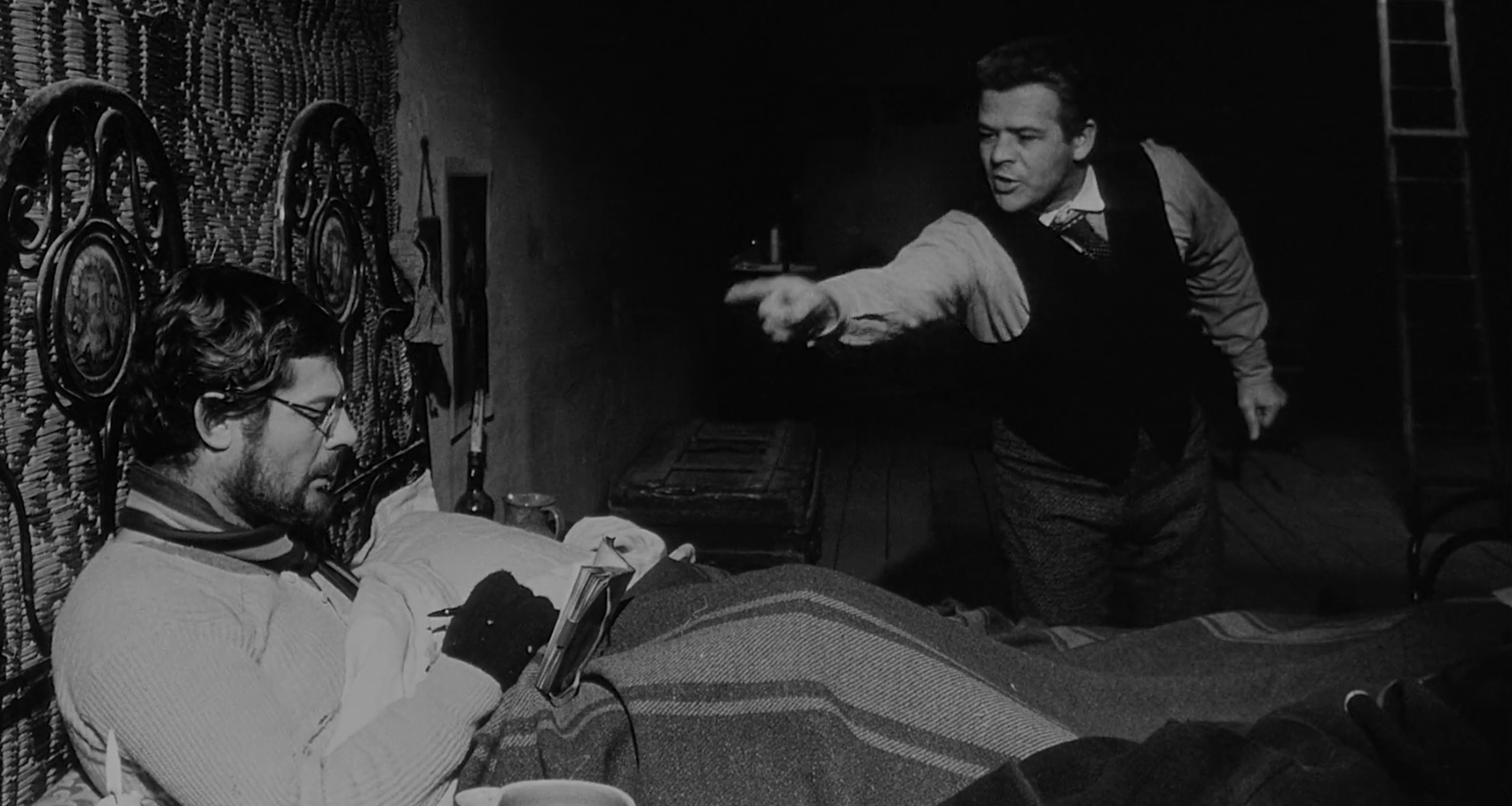

Alla fine il professore chiede: "Perché, invece delle mani, non prova a usare il cervello, le idee, se ne ha?"

"Infatti lei si è messo in mezzo solo per far vincere le sue idee balorde, mica per aiutarci!"

At last, the Professor asks, “Instead of using your hands, why don’t you try using your brain, ideas, if you have any?”

“In fact, you got involved just for your foolish ideas to win, not to help us!”

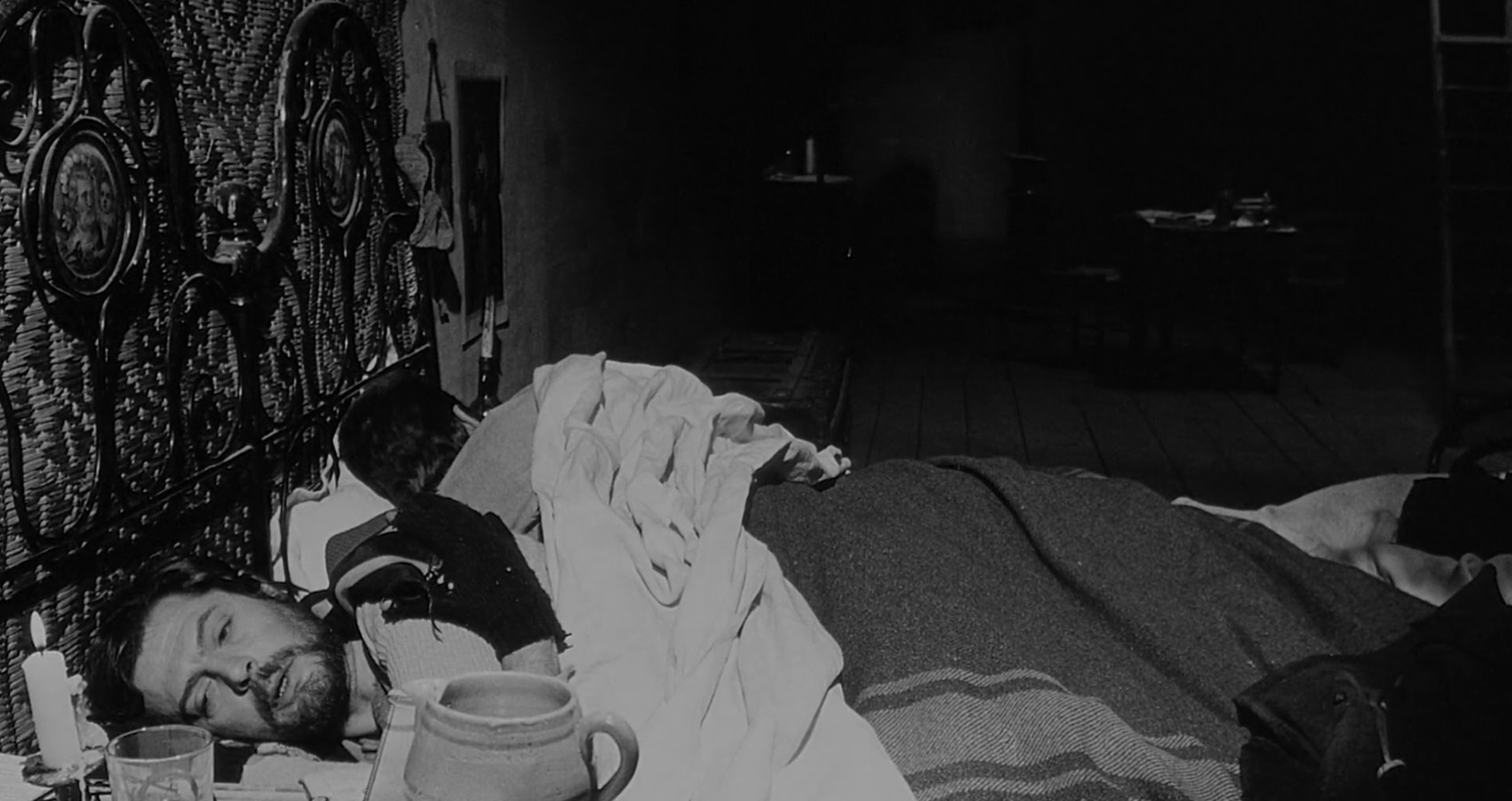

Spogliandosi, Raoul dice: "Perché tanto siamo bestie senza idee. Cosa importa a lei di noi?"

"Lei dice delle cose sciocche e ingiuste".

Undressing, Raoul says, “Because anyway we’re dumb animals with no ideas. Why should you care about us?”

“The things you’re saying are foolish and unfair.”

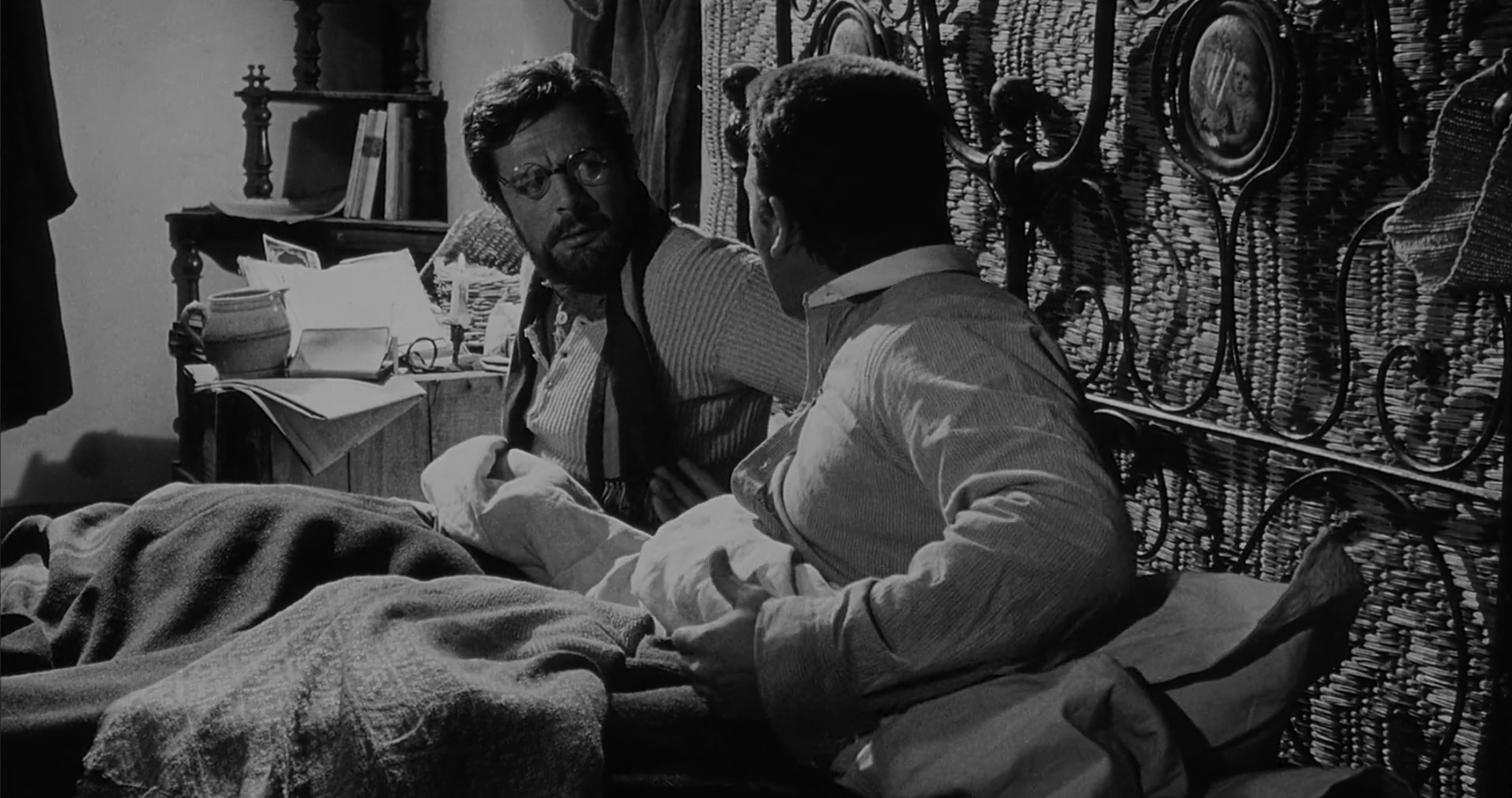

"Allora dica la verità: lei ci crede che ce la faremo?"

"Intanto siamo in pochi. E anche siamo divisi e anche sfiduciati, diciamolo pure. E loro sono forti, ben protetti, sicuri di sé".

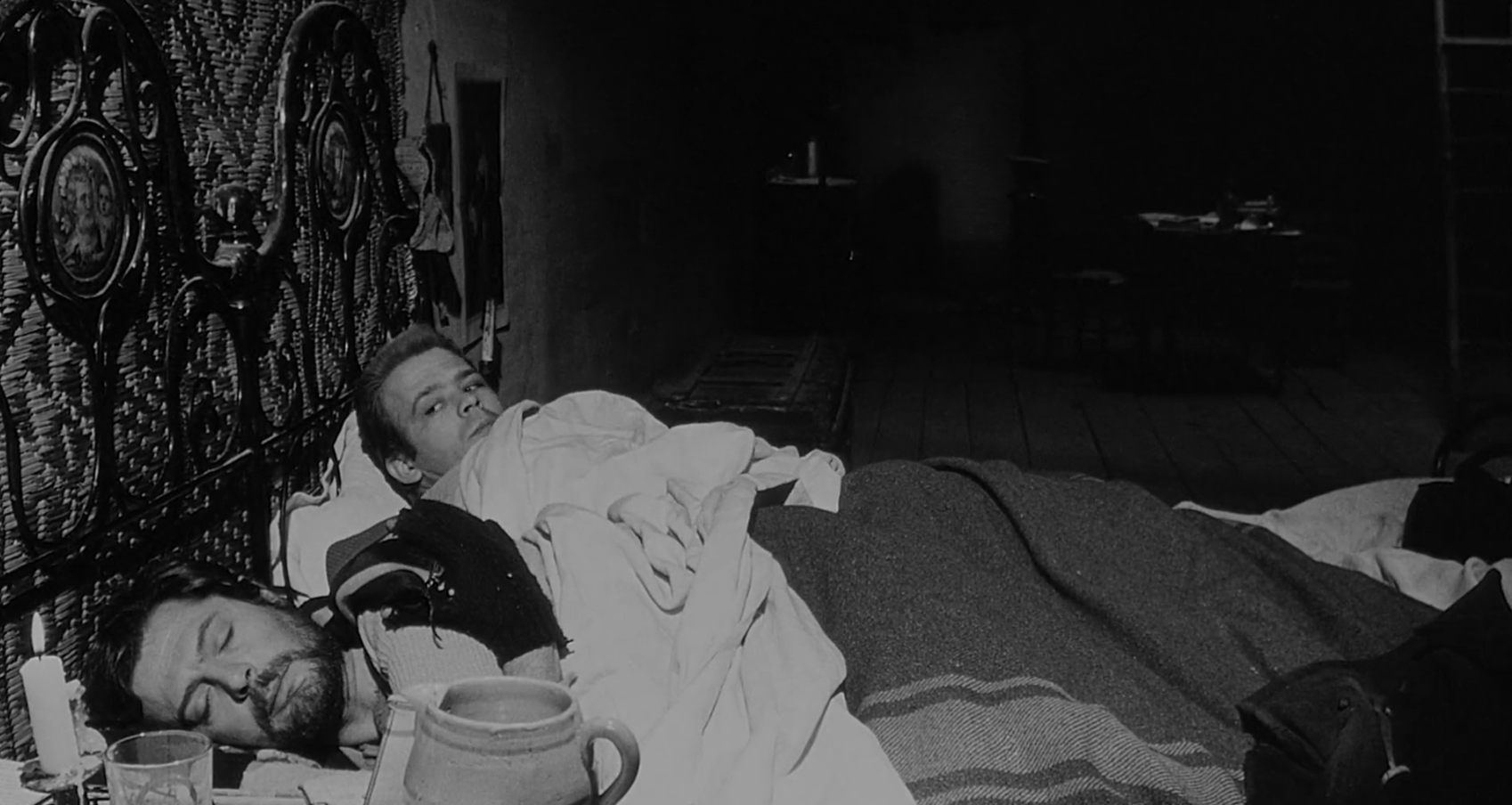

“Then tell me the truth: do you believe we can really pull this off?”

“First of all, there are few of us. And also, we’re divided and discouraged, let’s just say so. They’re powerful, well-connected, sure of themselves.”

"Qundi..." Il professore si pizzica il naso. "Non lo so. È difficile, anzi quasi impossibile".

"Allora sei matto. Sei un mascalzone", risponde Raoul. I due uomini sono seduti uno accanto all'altro. "Ci vuoi mandare tutti in malora!"

“So…” The Professor pinches the bridge of his nose. “I don’t know. It’s hard, even almost impossible.”

“Then you’re crazy. You're a scoundrel,” Raoul replies. The two men are sitting side by side. “You want to destroy us all!”

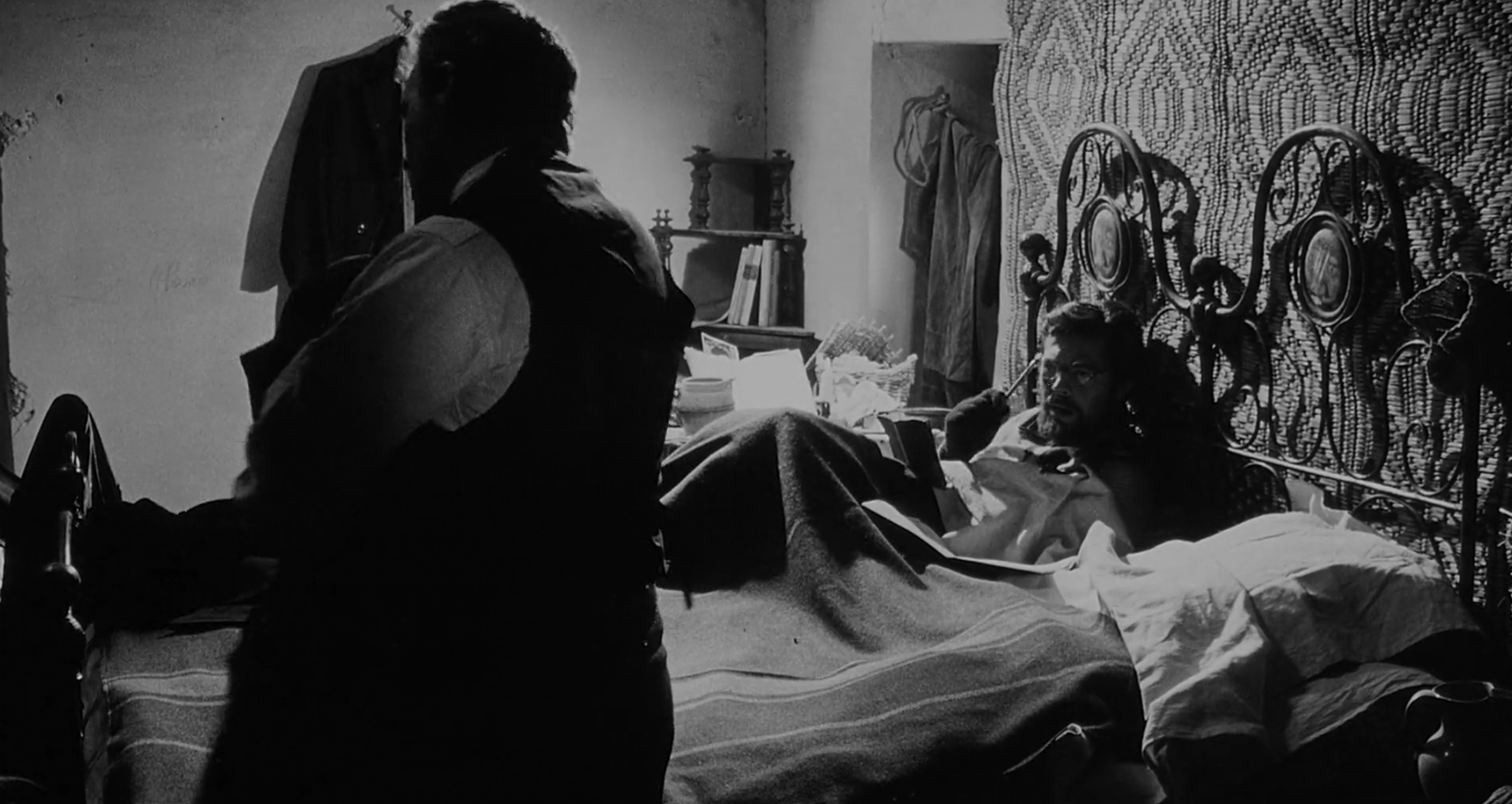

Guardandolo seriamente negli occhi, il professore dice: "Ma volete vincere al primo tentativo? Quando si è mai visto?! Sarebbe troppo comodo".

Gazing earnestly into his eyes, the Professor says, “But do you expect to win on the first attempt? When has that ever been seen?! That would be too easy.”

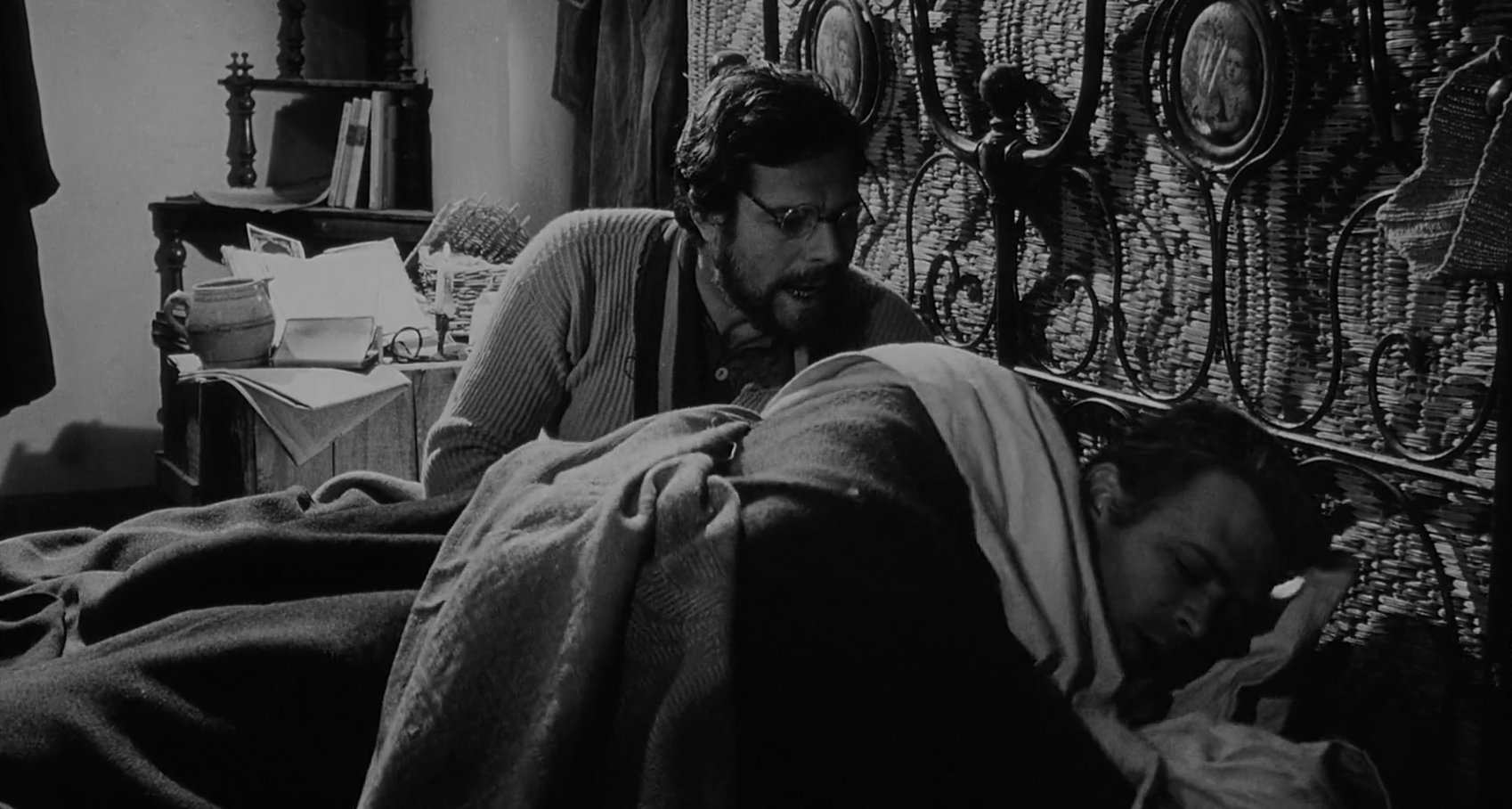

Raoul si volta, tirandosi addosso le coperte.

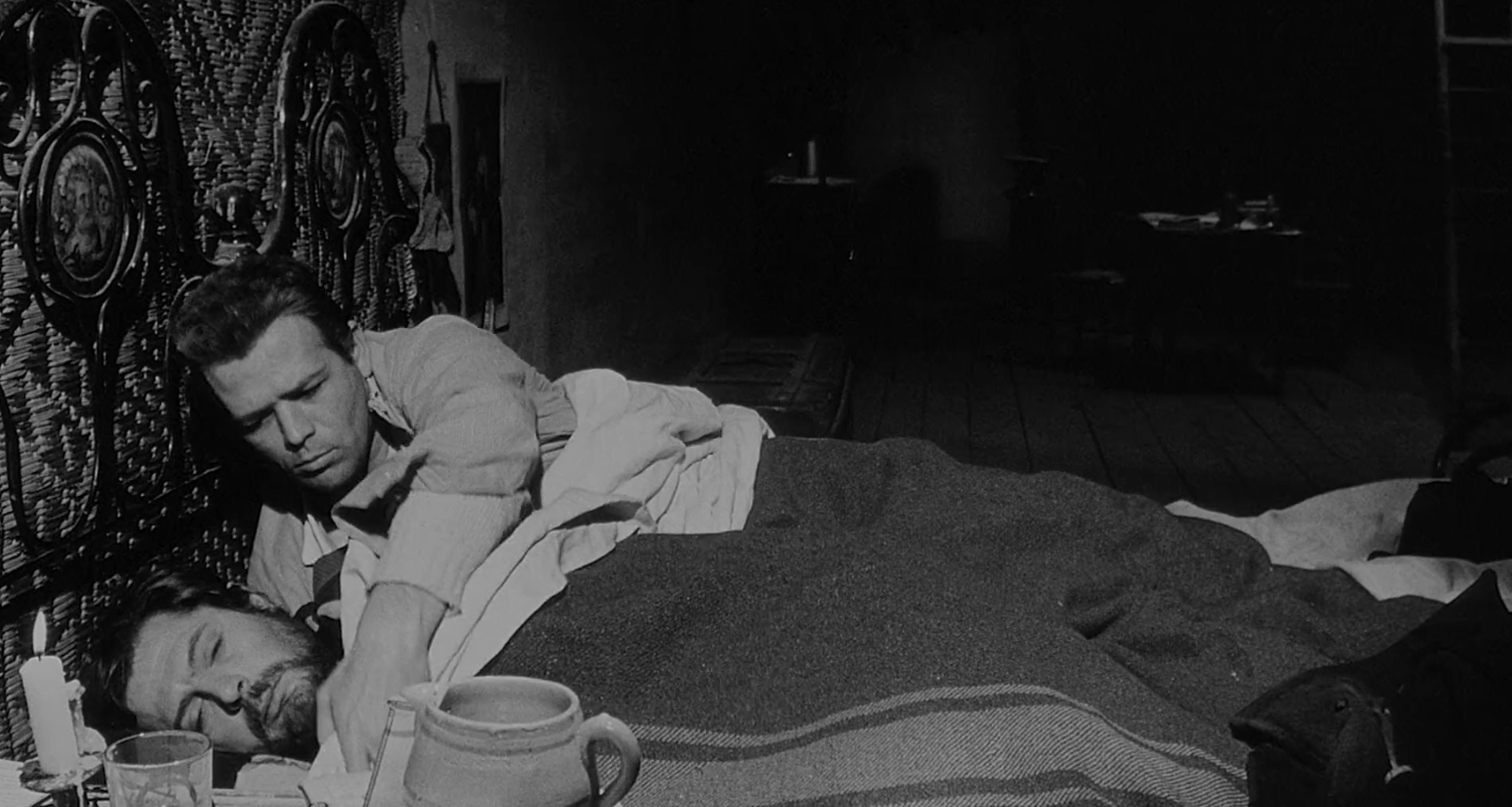

"Dovete tener duro, dovete fargliela pagare cara" – dice il professore, chinandosi su di lui – "Dovete fargli capire che la prossima volta sarà ancora più dura. E questa sarebbe già una grande vittoria. La coperta!" Ruba la coperta a Raoul e si sdraia.

Raoul turns away, pulling the covers over himself.

“You have to hold out, you have to make them pay dearly,” says the Professor, leaning over him. “You have to make them understand that the next time it will be even harder. And that in itself would be a great victory. The covers!” He steals the blanket from Raoul and lies down.

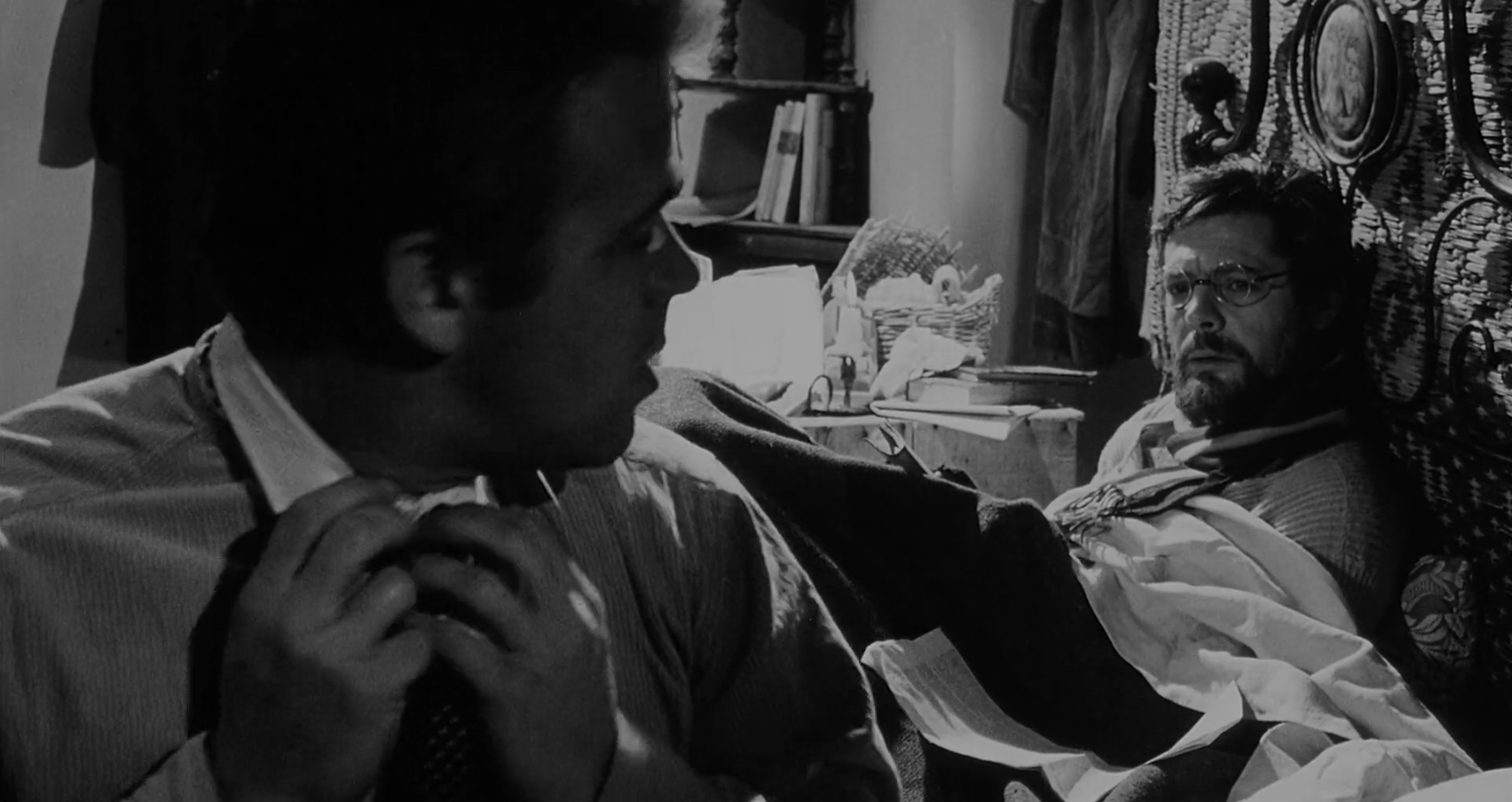

Raul si volta verso di lui. "Però a correre tutti i rischi siamo noi! Cosa te ne importa?" Tira di nuovo le coperte a sé.

Raul turns to him. “But it’s us running all the risks! What do you care?” He yanks the covers back.

"Tu non sei uno di noi" – dice assonnato – "Così come sei arrivato, te ne vai".

"Hai ragione. Non sono come voi io. Non ho una casa, né una famiglia, né amici".

Sentiamo una melodia dolce e malinconica.

“You’re not one of us,” he says sleepily. “The way you arrived, you’ll go away.”

“You’re right. I’m not like you all. I have no home, no family, no friends.”

We hear a sweet, melancholy melody.

"Non ho nessuno che mi cerca, tranne la polizia".

Raoul alza la testa. "Allora perché lo fai?"

Mezzo addormentato, il professore parla con gli occhi chiusi. "Perché lo faccio? Perché ho la testa piena di idee balorde".

“No one’s interested in me, except the police.”

Raoul raises his head. “So why are you doing this?”

Half asleep, the Professor talks with his eyes closed. “Why am I doing this? Because my head is full of foolish ideas.”

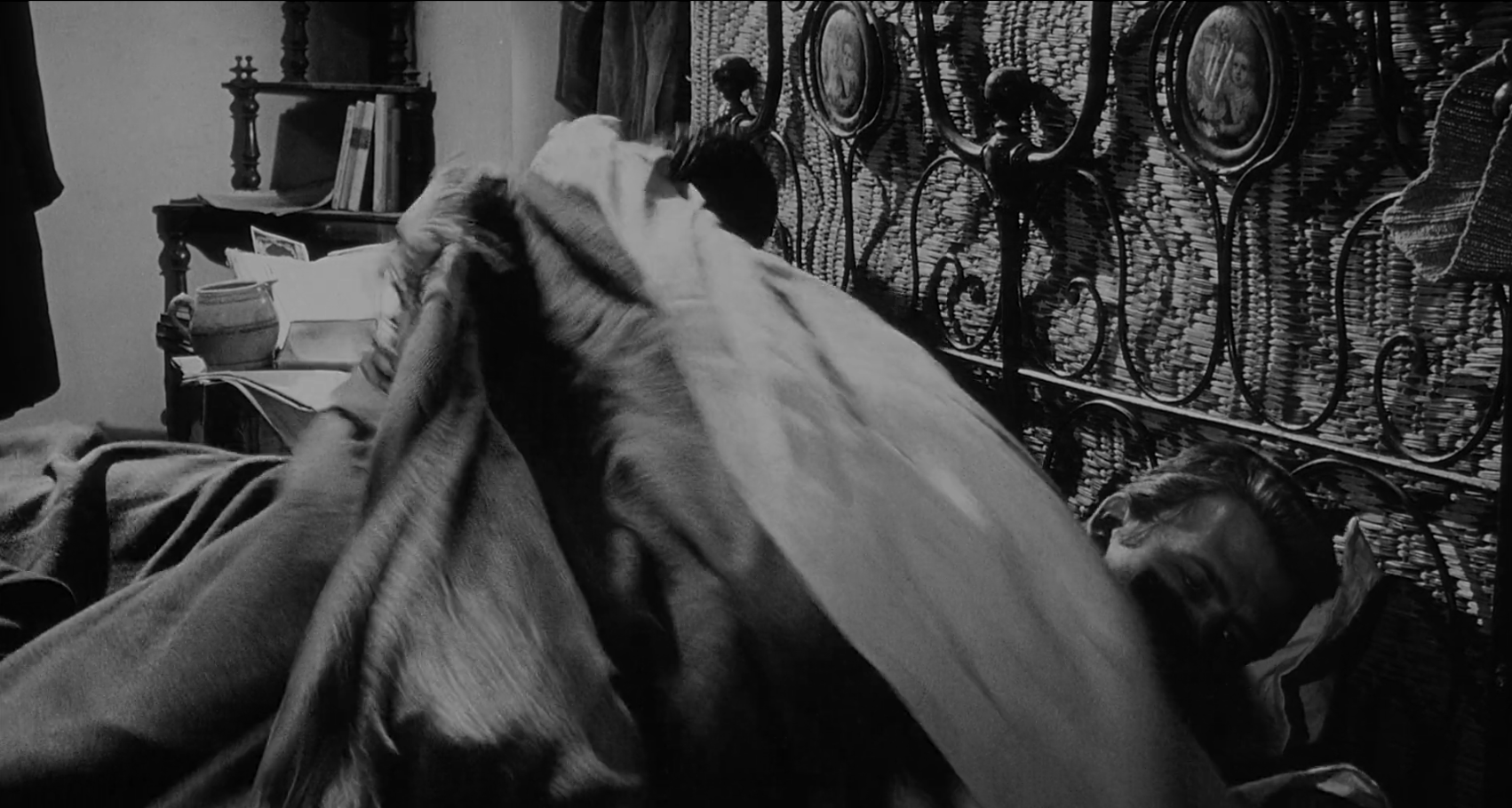

Raoul tira su le coperte sul professore, si allunga sopra di lui e spegne la candela.

Raoul pulls the covers up over the Professor, leans over him, and blows out the candle.

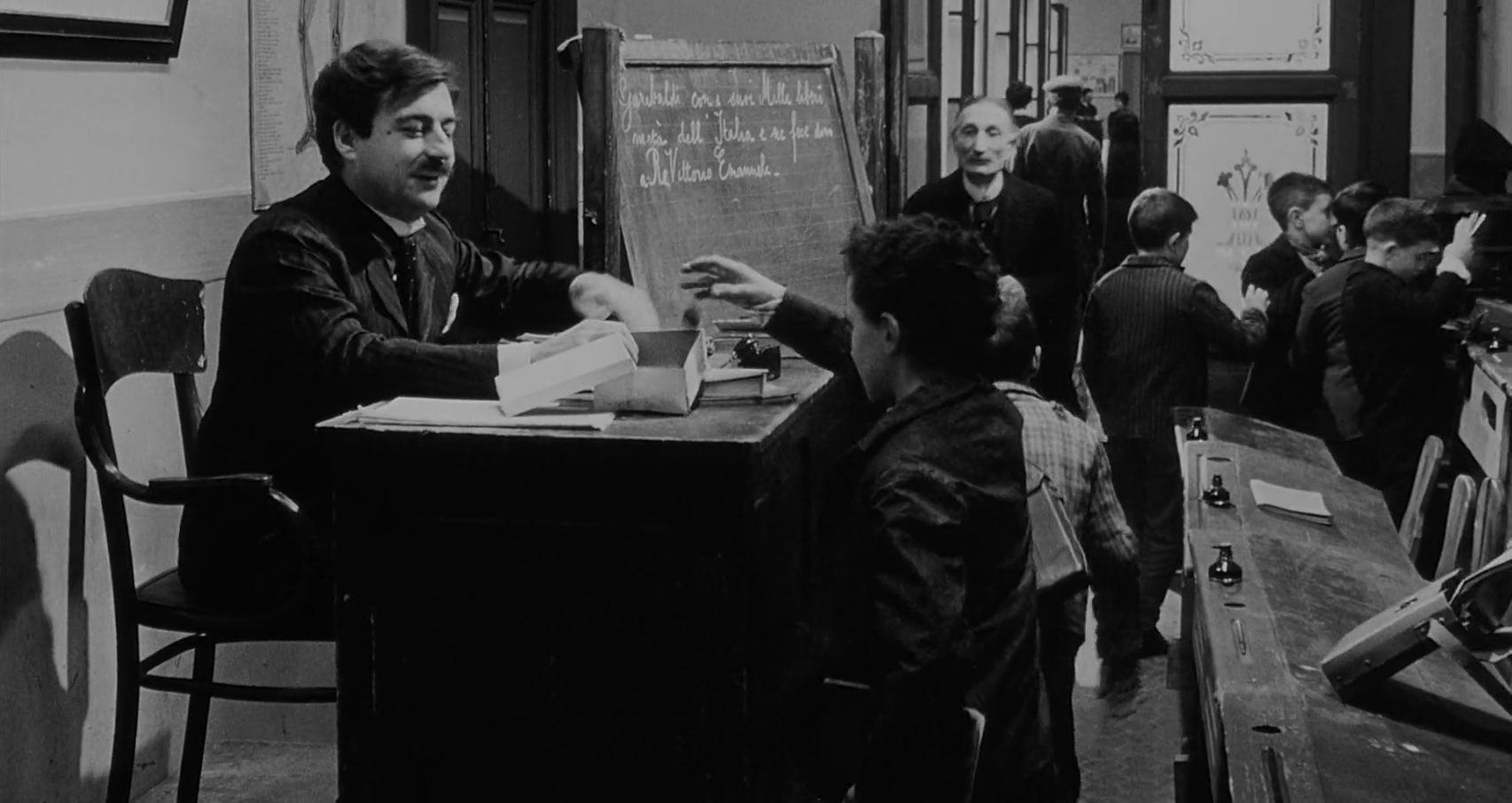

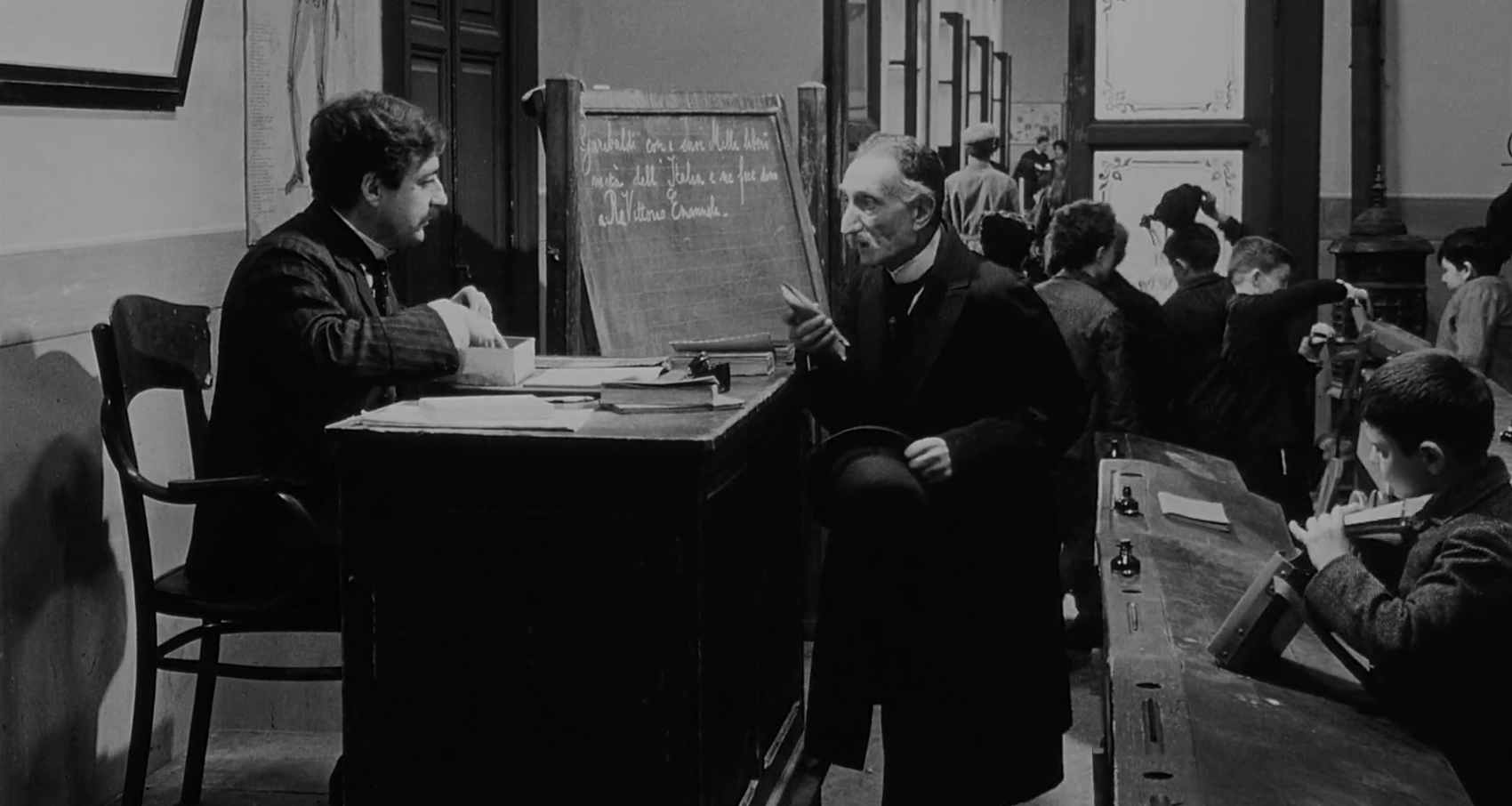

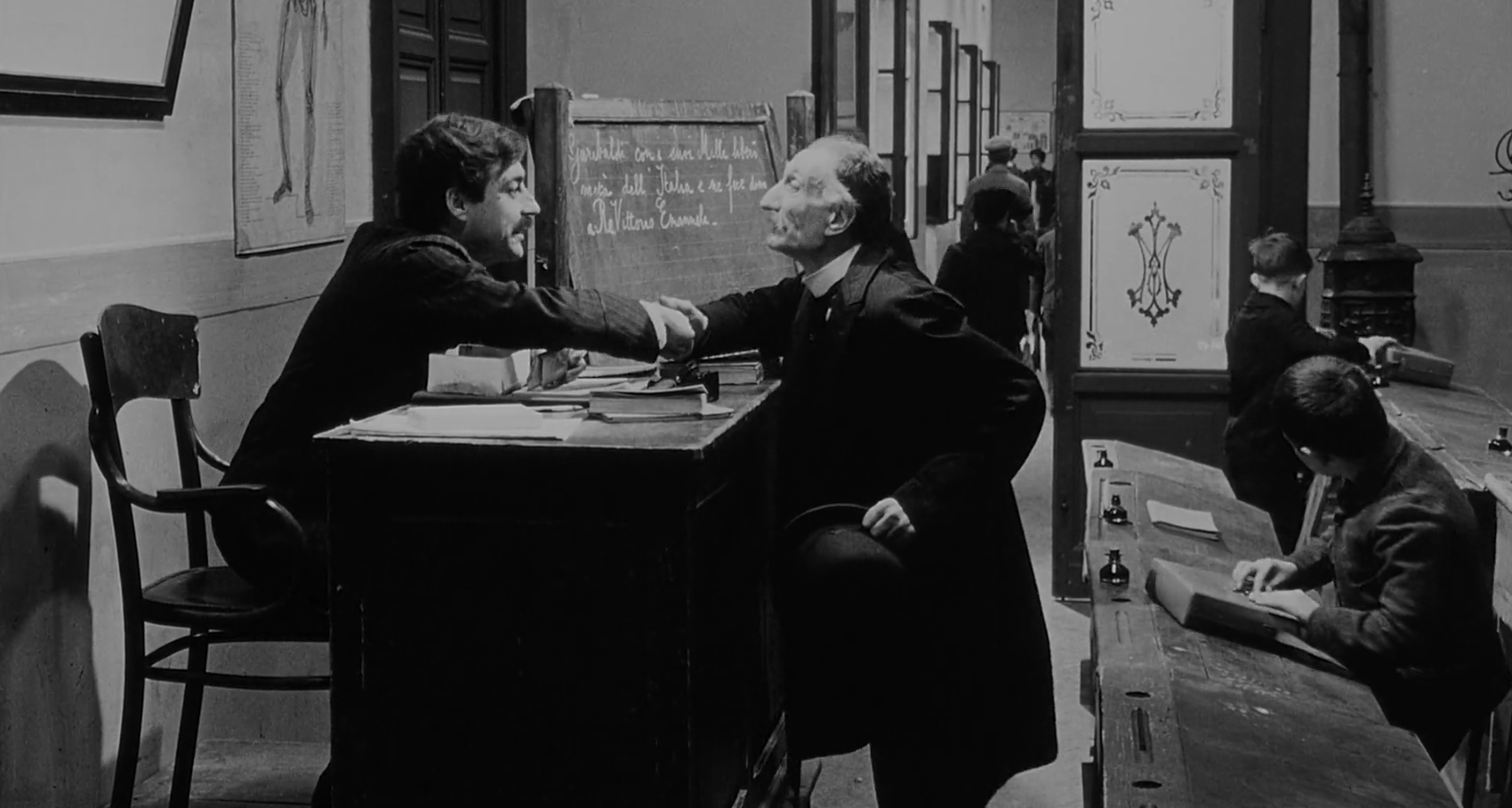

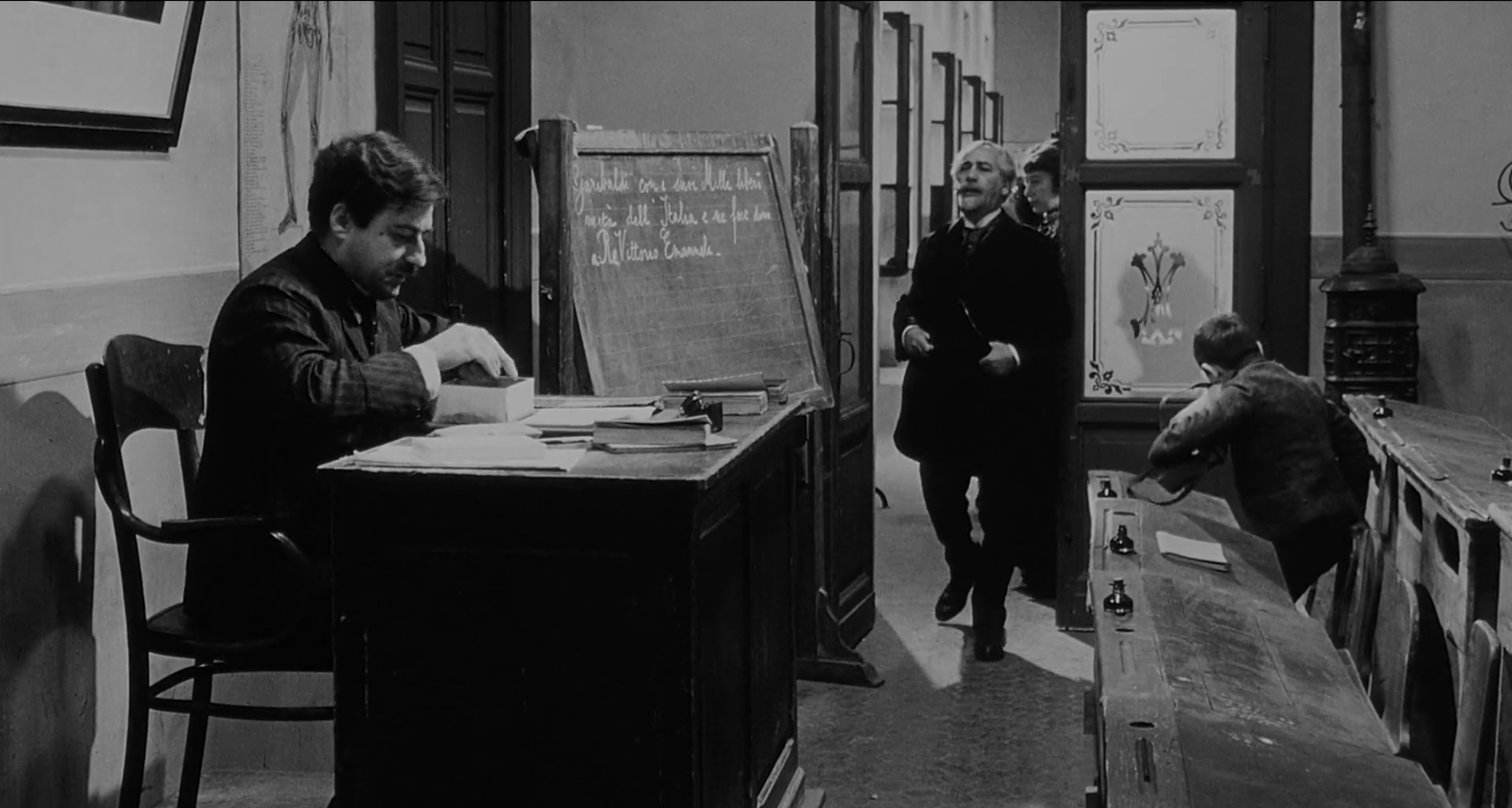

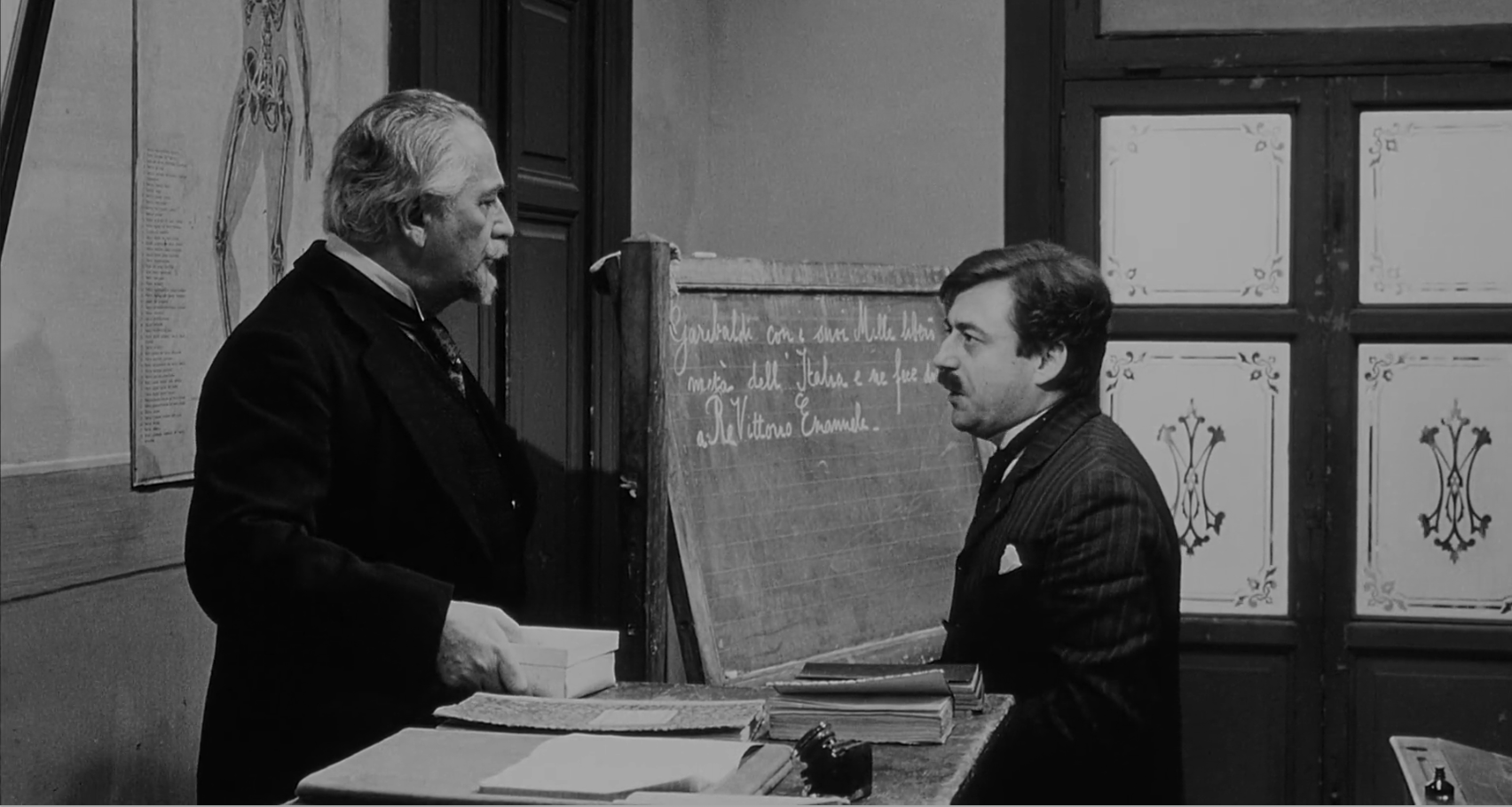

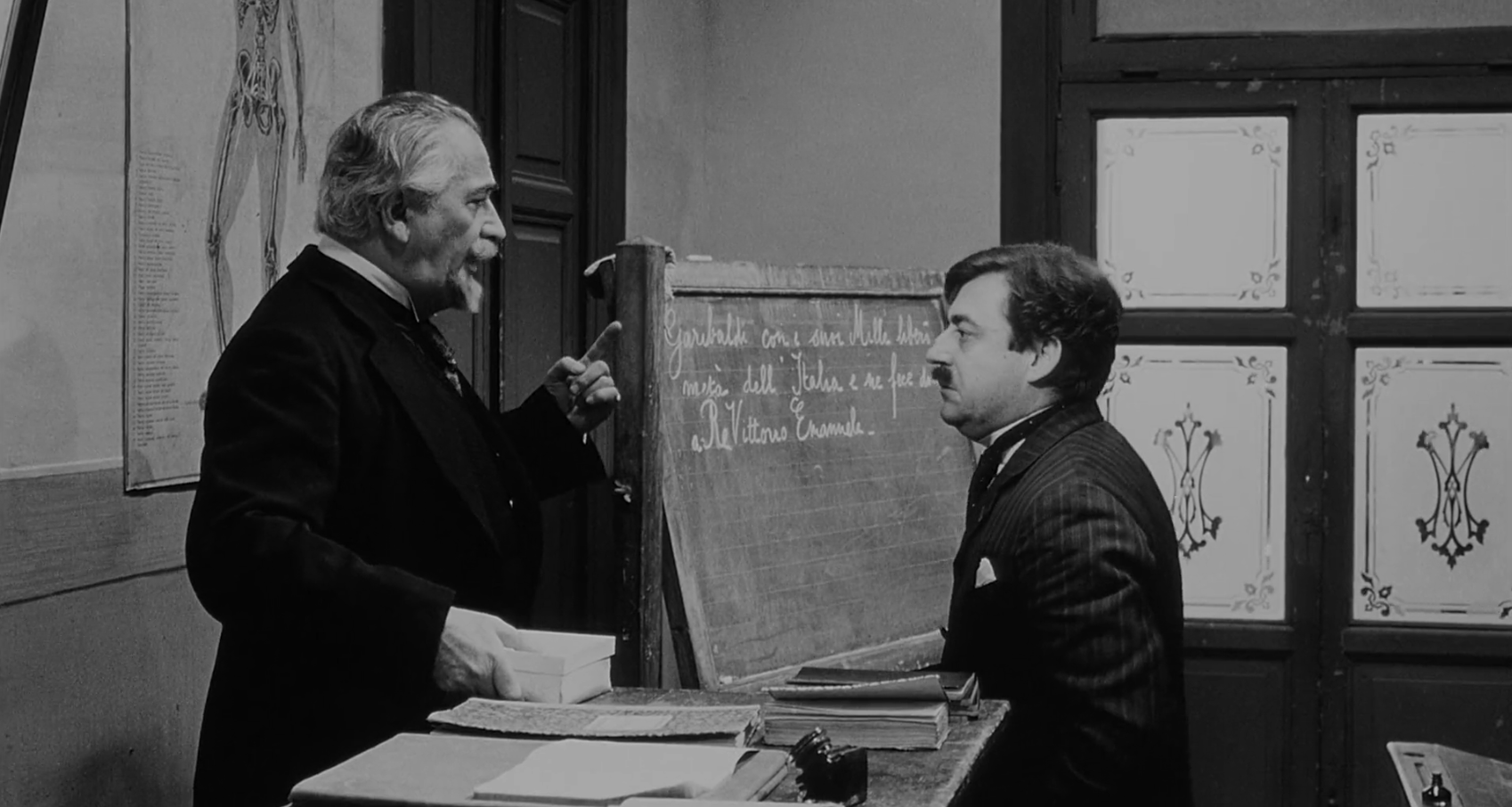

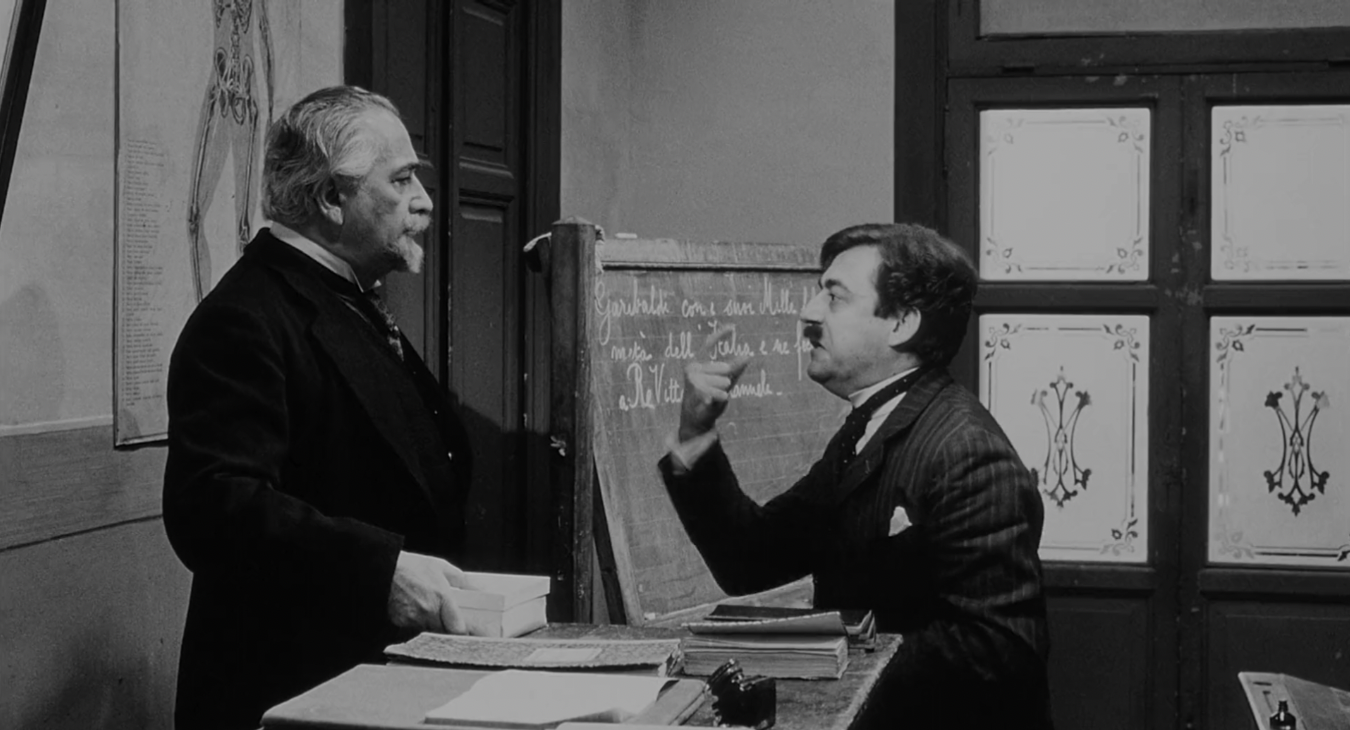

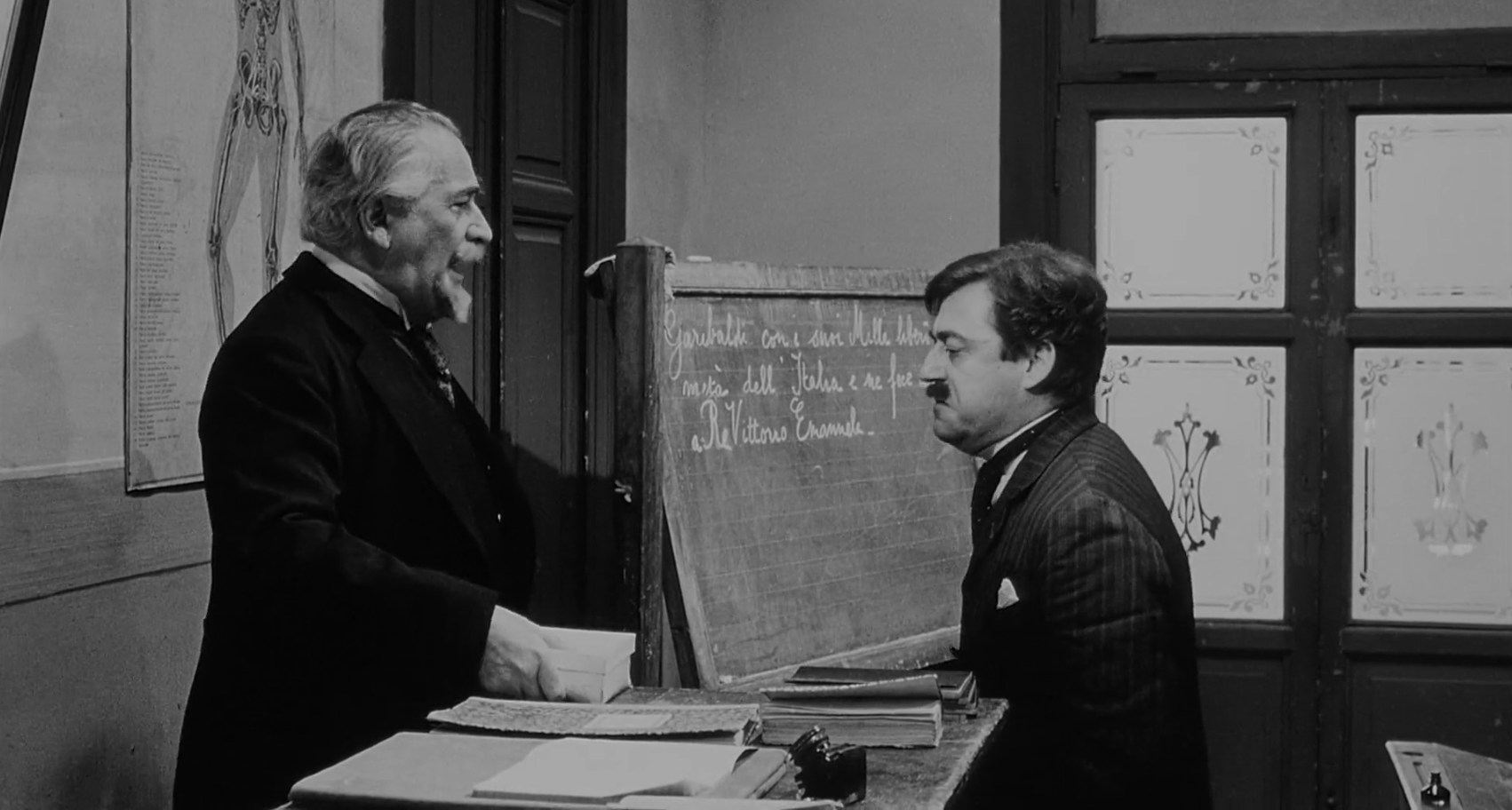

A scuola. L'insegnante è seduto alla sua cattedra. Quando i bambini escono dalla classe, lasciano cadere delle monete in una scatola di cartone.

At school. The teacher sits at his desk. As the children leave the classroom, they drop coins into a cardboard box.

Un altro insegnante si avvicina, consegnando alcune buste. "Tieni: dalle classi prima, seconda e terza".

"Grazie". Gli uomini si stringono la mano.

Another teacher approaches, delivering some envelopes. “Here: from first, second and third grades.”

“Thank you.” The men shake hands.

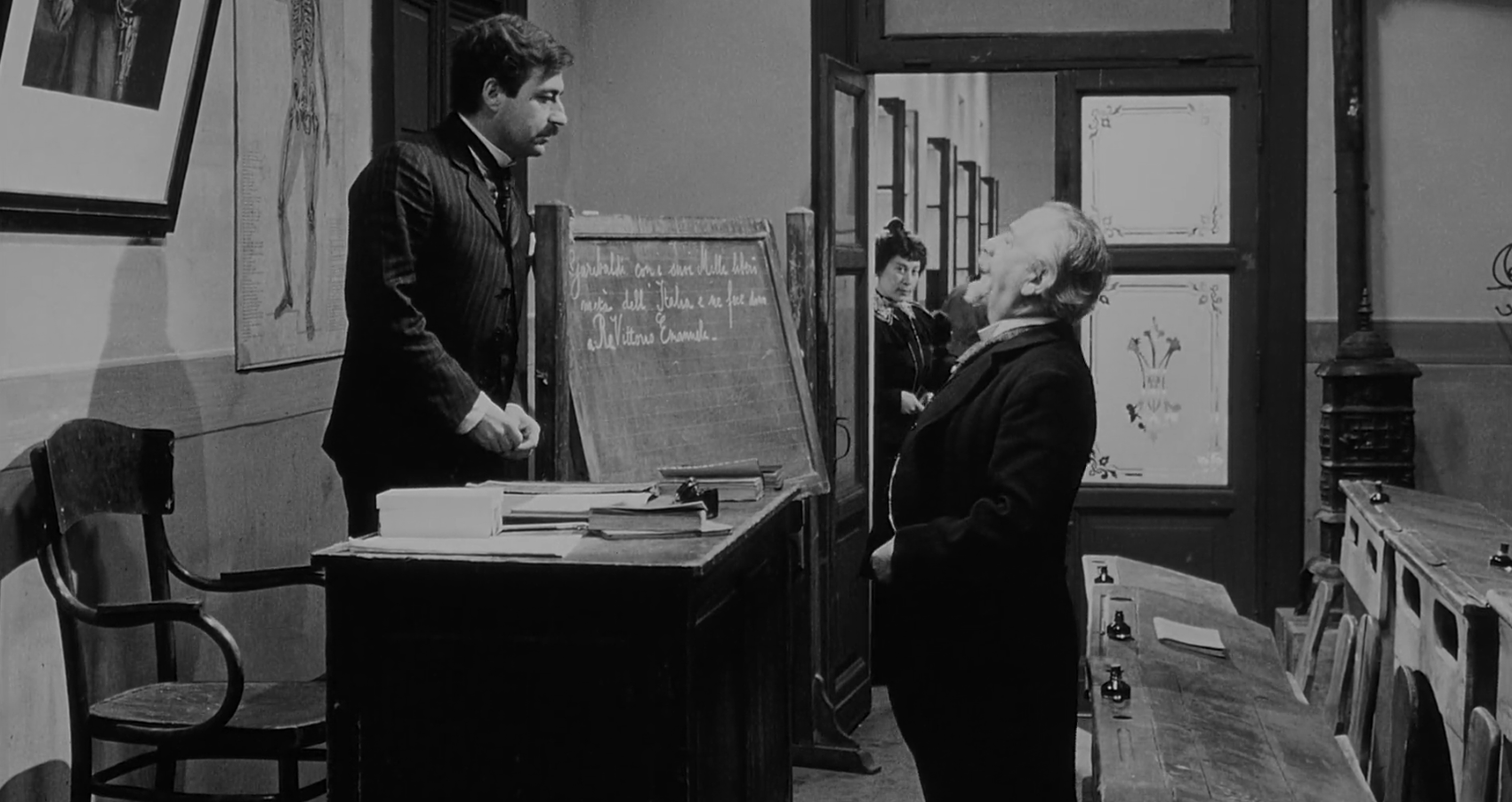

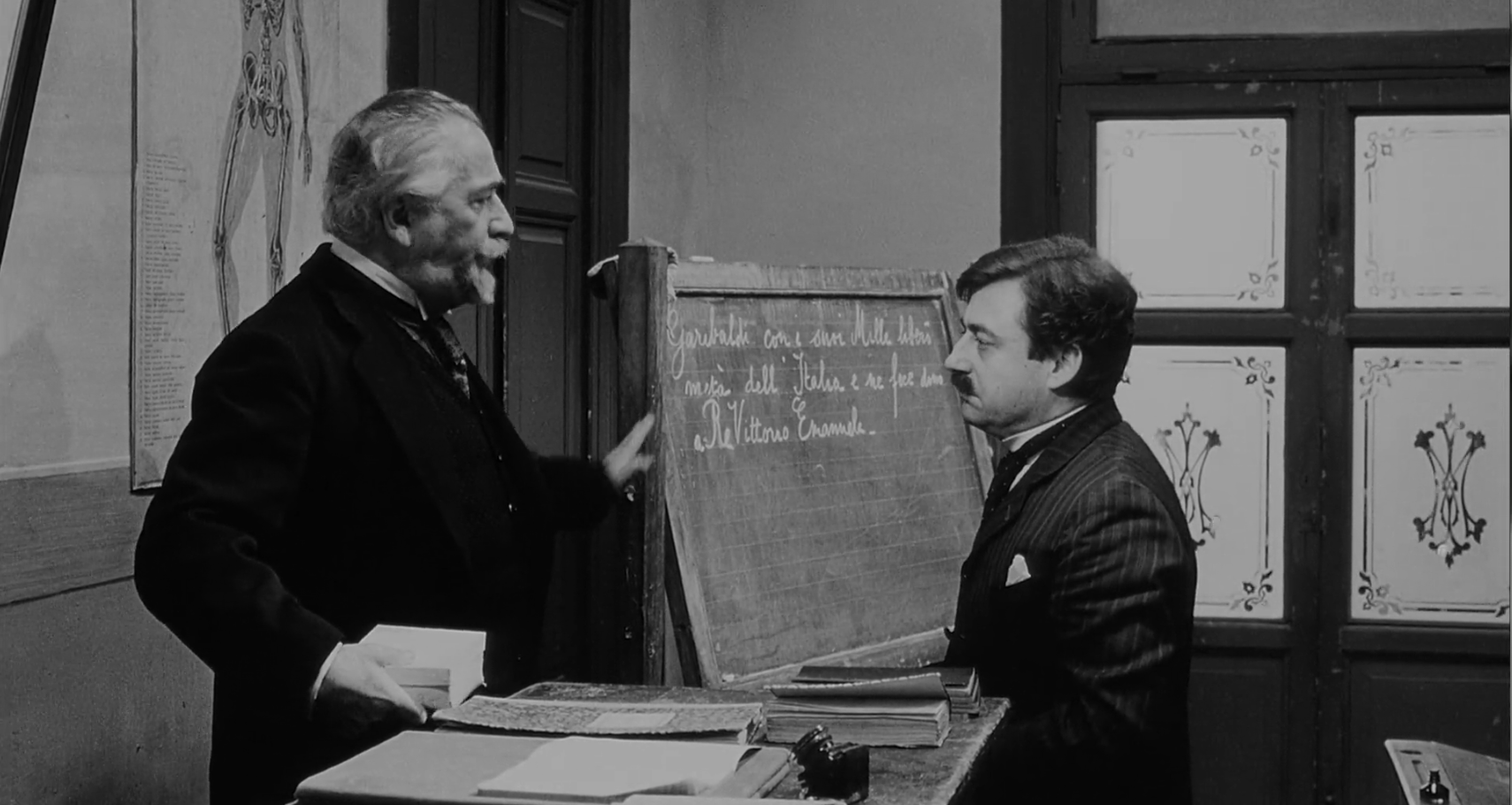

Entra il direttore della scuola. "Senta Di Meo, ieri le ho detto che c’è stata una lamentela del Provveditorato. Si può essere umani senza essere socialisti".

"Cosa c'entra?"

The school principal enters. “Listen, Mr. Di Meo, I told you yesterday that there was a complaint from the Board of Education. One can be human without being a socialist.”

“What’s the problem?”

"Ora vengo a sapere che lei, in dispregio al mio esplicito ordine, ha promosso un'altra di quelle sue collette". Mentre l'insegnante va a chiudere la porta, il direttore prende la scatola dalla sua cattedra.

"Ma cosa fa?!"

"Li sequestro e li farò restituire ai ragazzi".

“Now, I’ve come to learn that you, in defiance of my explicit order, you’ve organized another one of your collections.” As the teacher goes to close the door, the principal takes the box from his desk.

“But what are you doing?!”

“I’m confiscating it and returning it to the children.”

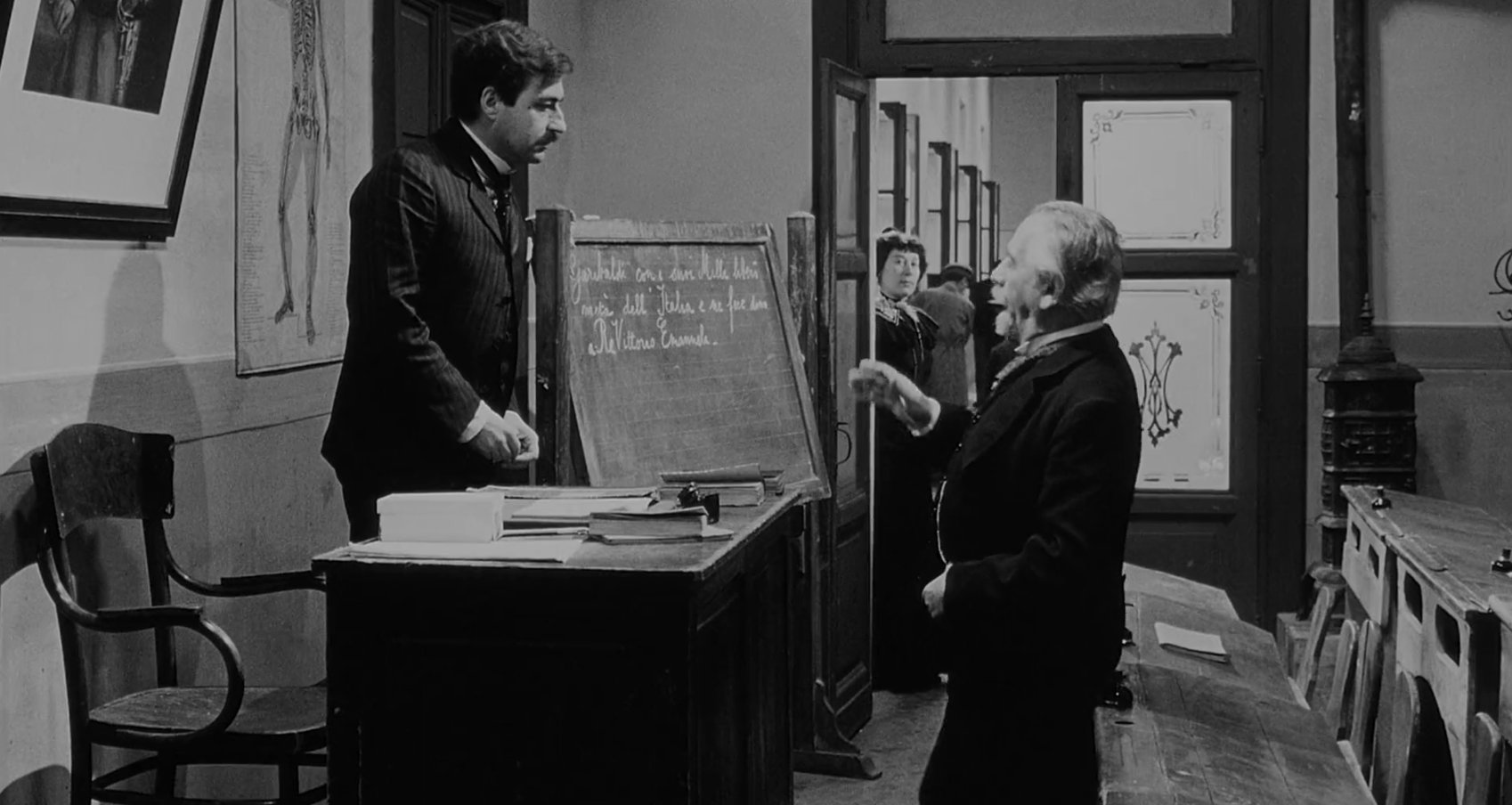

Alzando la voce, il direttore continua: "Insegni agli alunni i concetti che li aiuteranno a essere buoni cittadini, punto e basta! Questo è quanto! Lei non ha il permesso di svolgere attività sovversive!"

"È solo un atto di solidarietà per un povero operaio morto! Un gesto civile ed educativo, soprattutto per dei bambini".

Voice rising, the principal continues, “Teach your pupils the concepts that will help them be good citizens, period! That’s it! You don’t have permission to engage in subversive activities!”

“It’s only an act of solidarity for a poor dead worker! A civil and educational gesture, above all for the children!”

Con rabbia, l'insegnante chiede: "E invece noi insegniamo che è giusto che al mondo ci siano servi e tiranni".

"Basta! Scriverò al Provveditorato!"

Angrily, the teacher says, "And instead, we teach that it is okay for there to be servants and tyrants in the world."

“That’s enough! I’m going to write to the Board of Education!”

La giornata a scuola è finita! I bambini escono di corsa in una strada brulicante di attività: un venditore che tira il suo carretto, un uomo che tiene in equilibrio un vassoio di pane sulla testa, due soldati che passeggiano.

The school day is over! The children come running out into a street bustling with activity: a vendor pulling his cart, a man balancing a tray of bread on his head, two strolling soldiers.

Omero aspetta fuori dalla scuola con il suo fratellino. Quando l'insegnante esce, Omero gli chiede: "Mi scusi, signor maestro. Volevo sapere come va mio fratello Pierino con lo studio".

"Non è che sia stupido, ma studia poco. Insomma, non va tanto bene. Di’ a alla mamma di stargli un po’ dietro".

Omero waits outside the school with his little brother. When the teacher emerges, Omero asks him, “Excuse me, sir. I wanted to know how my brother Pierino is doing with his studies”.

“It’s not that he’s stupid, but he doesn’t study much. So he’s not doing so well. Tell your mother to keep after him a little.”

Omero aspetta che abbiano girato un angolo e poi spinge suo fratello con forza contro un muro, colpendolo. Lo sgrida: "Tu devi studiare! Studiare!"

"Non mi piace, io non voglio andare a scuola! Voglio andare in fabbrica come te!"

Omero waits until they’ve turned a corner, and then pushes his brother hard against a wall, hitting him. He yells at him, “You have to study! Study!”

“I don’t like it, I don’t want to go to school! I want to go to the factory like you!”

"Devi prendere il diploma, capisci?"

Il bambino cade a terra. I suoi libri finiscono sul ciottolato.

“You have to graduate, understand?”

The little boy falls down. His books end up on the cobblestones.

Pierino si rialza. Vediamo i buchi nella sua giacca stracciata.

Omero lo avverte: "Piuttosto di lasciarti fare come me, io ti ammazzo!"

Pierino stands back up. We see the holes in his raggedy jacket.

Omero warns him, “Before I let you do what I do, I’ll kill you!”

Raccoglie i libri, rimette delicatamente il cappello del bambino sulla sua testa e asciuga le sue lacrime con un panno.

He picks up the books, gently puts the boy’s hat back on his head and dries his tears with a cloth.

I fratelli camminano mano nella mano verso casa.

The brothers walk hand in hand toward home.

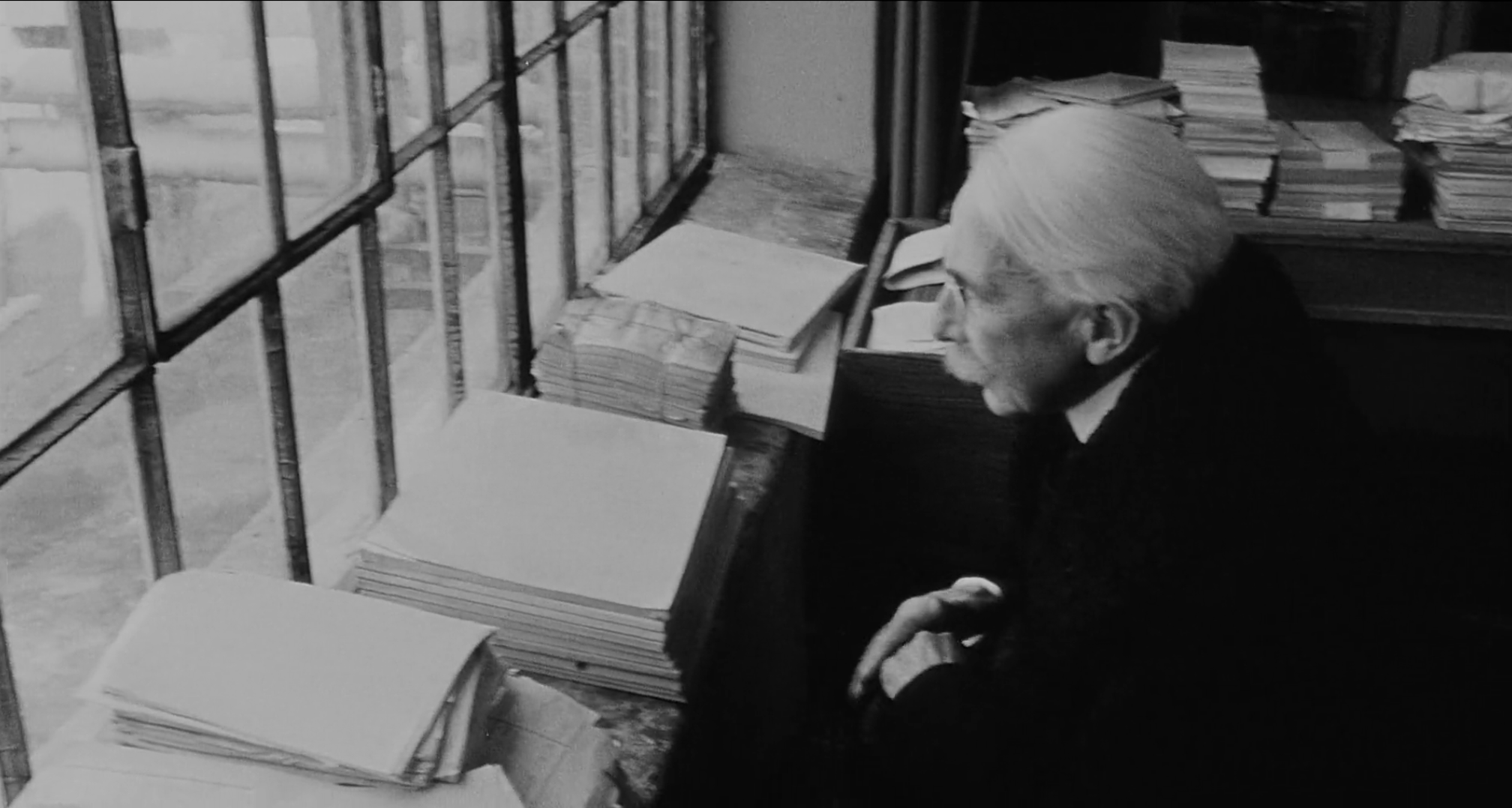

Una bella vista invernale dell’esterno della fabbrica dall'ufficio di Baudet: l'immagine è divisa in piccole forme geometriche da un albero spoglio, i binari della ferrovia, un cavallo e una carrozza, le linee di un tetto.

A beautiful winter view of the outside of the factory from Baudet’s office: the image is divided into small geometric shapes by a bare tree, the railroad tracks, a horse and carriage, the lines of a roof.

Alla finestra, il proprietario si lamenta: "Vagabondi! Fannulloni!"

At the window, the owner complains, “Bums! Lazy good for nothings!”

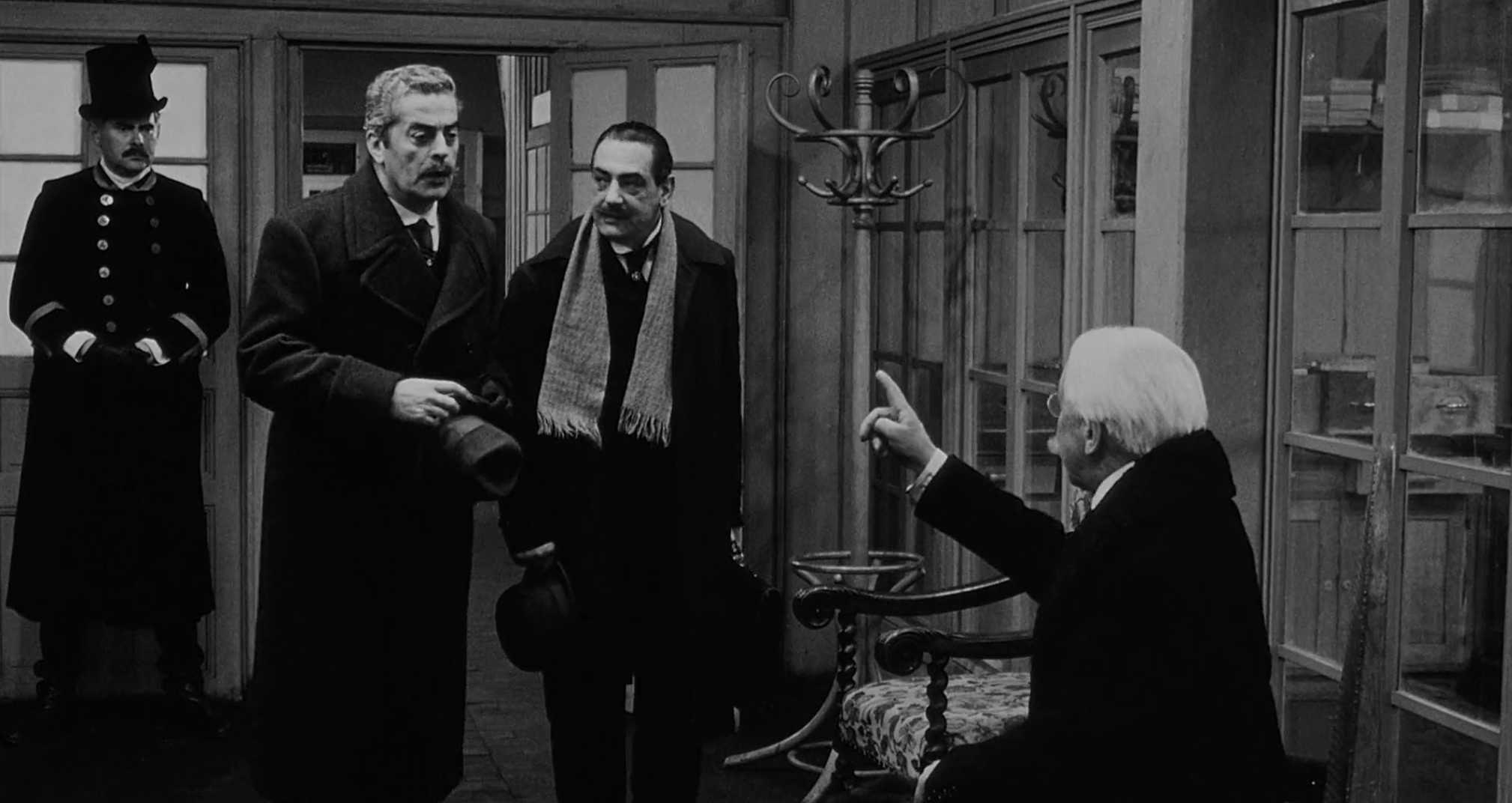

Quando Baudet e il nipote arrivano, il proprietario li sgrida per il ritardo. Cercano di spiegare, ma lui li interrompe.

When Baudet and the nephew arrive, the owner yells at them for being late. They try to explain, but he cuts them off.

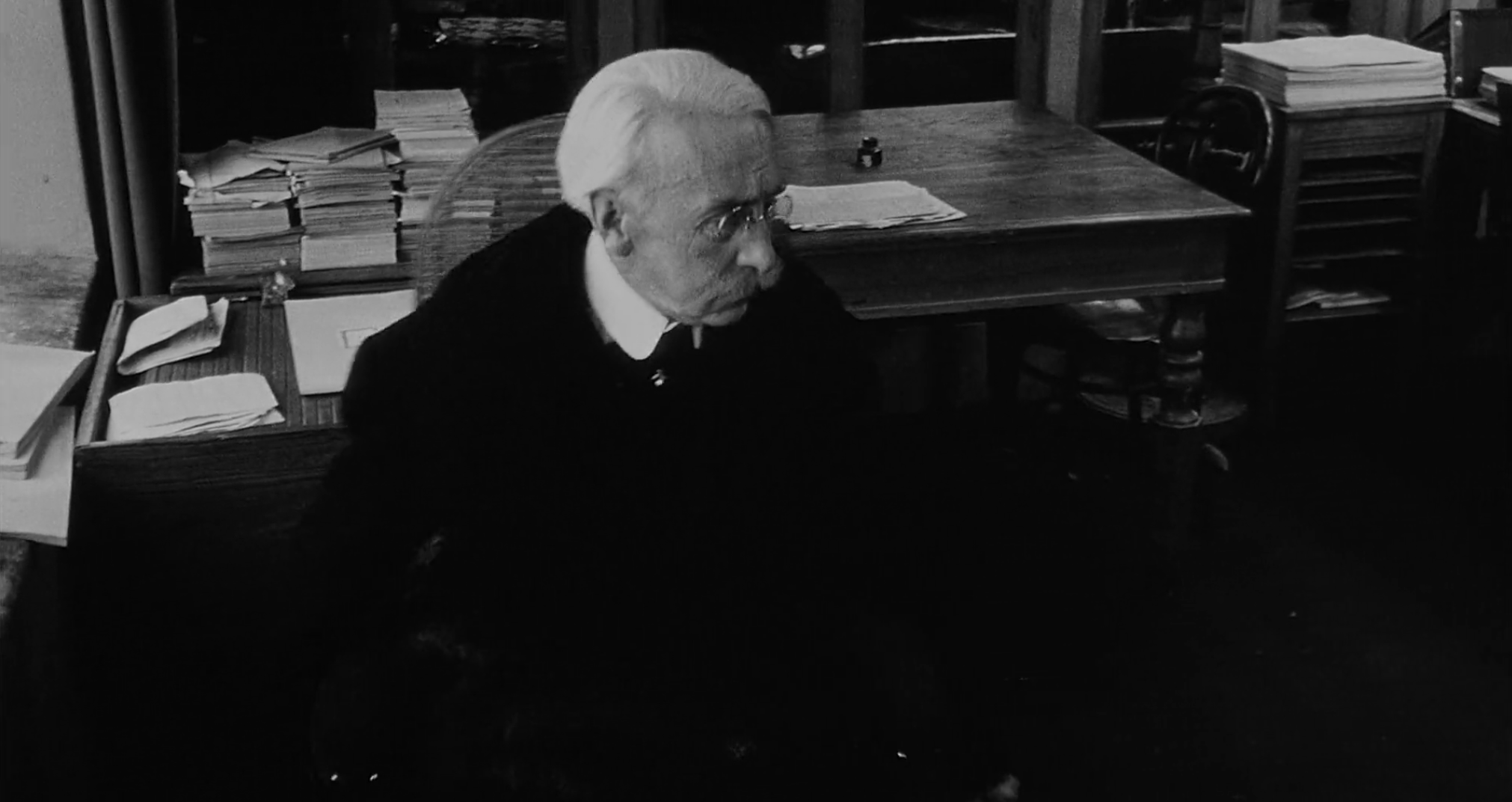

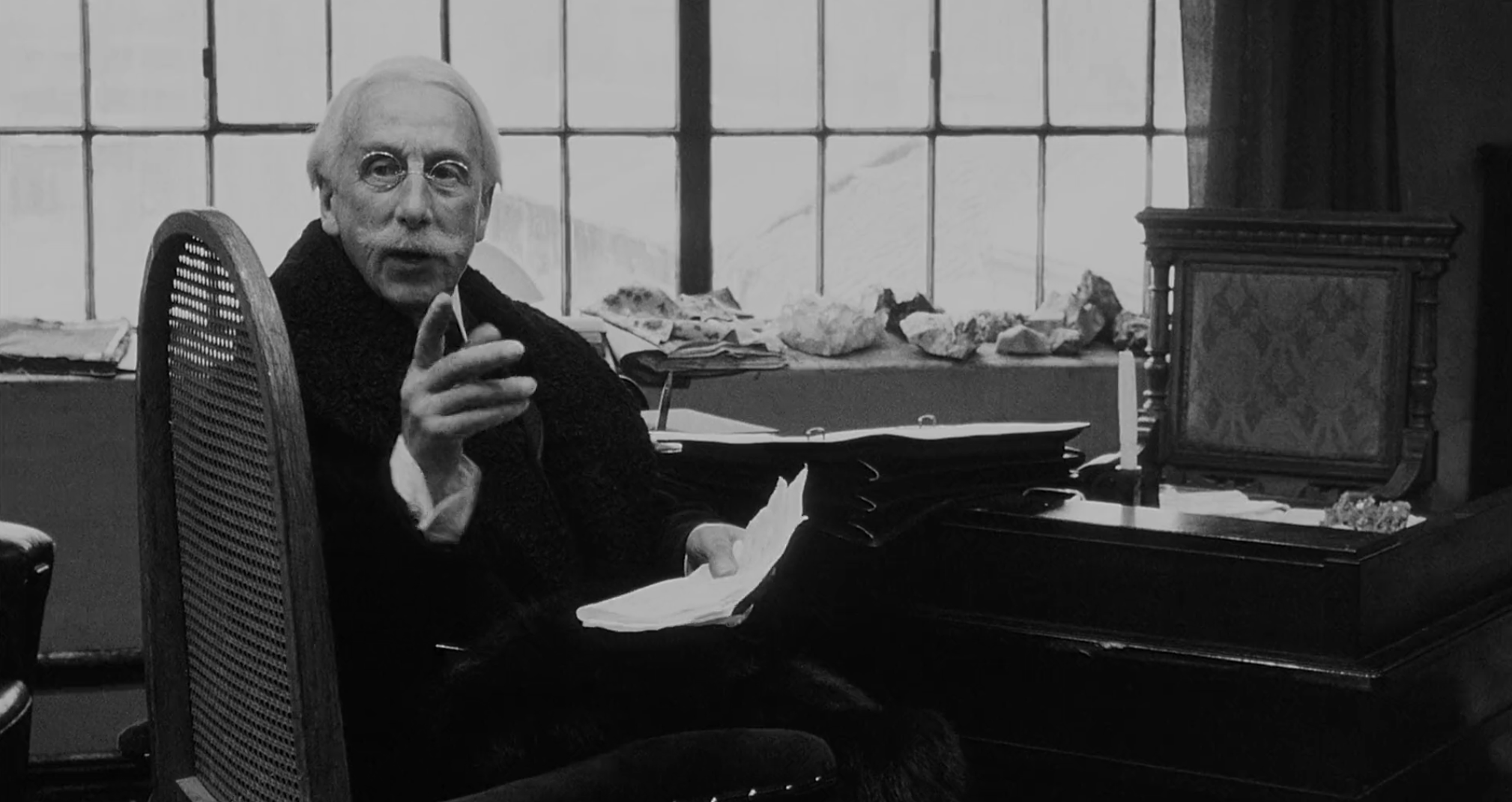

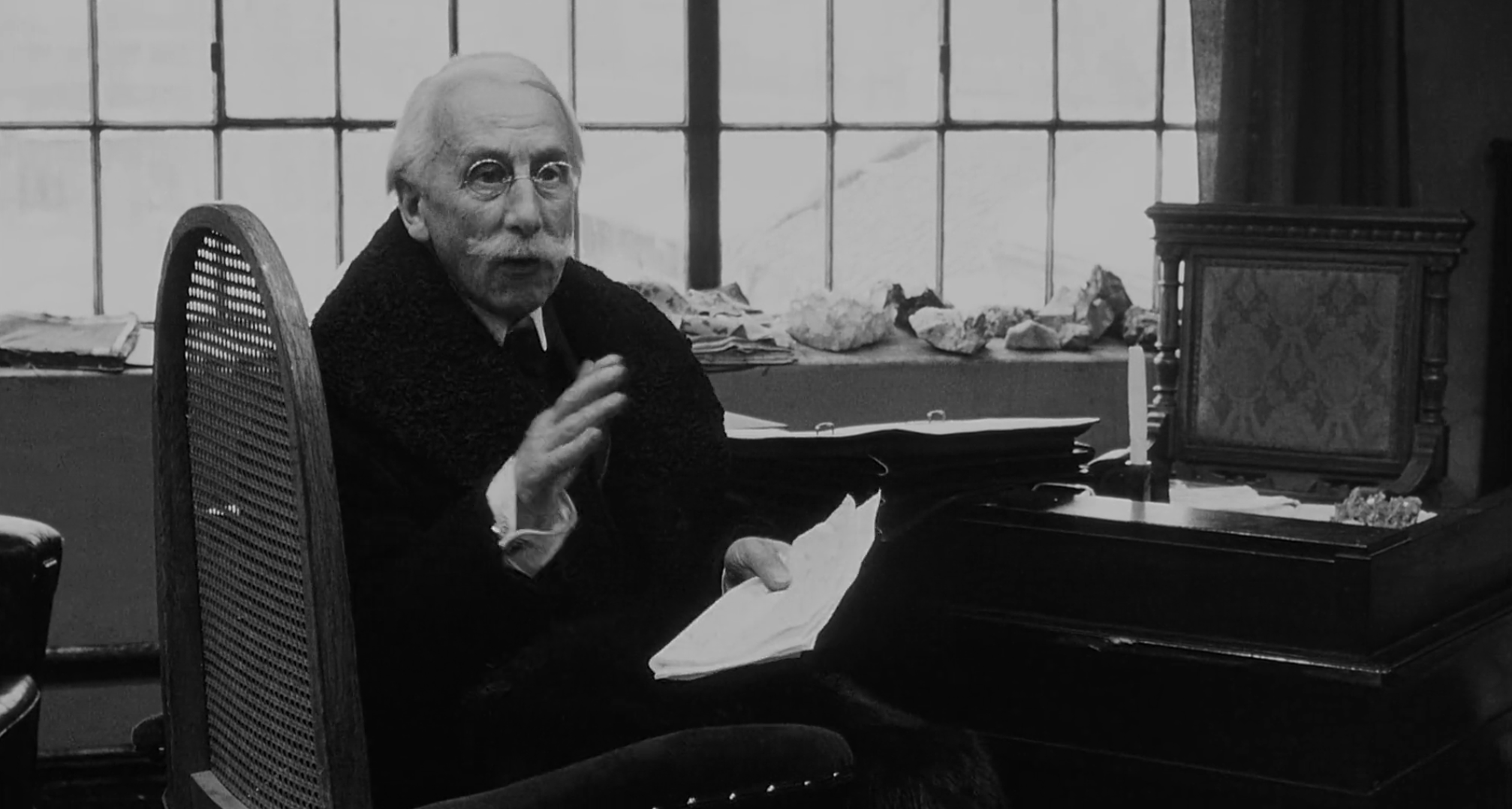

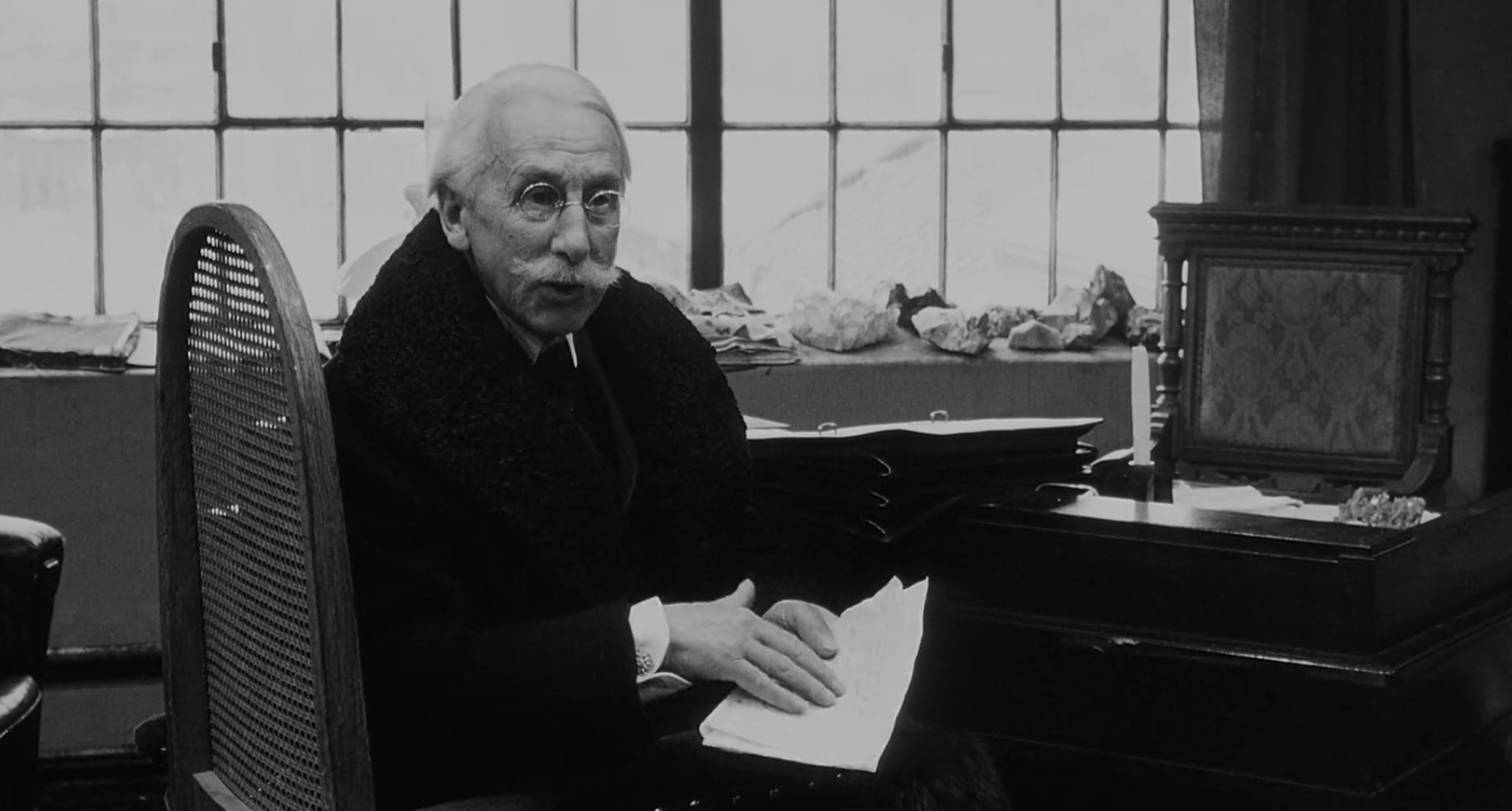

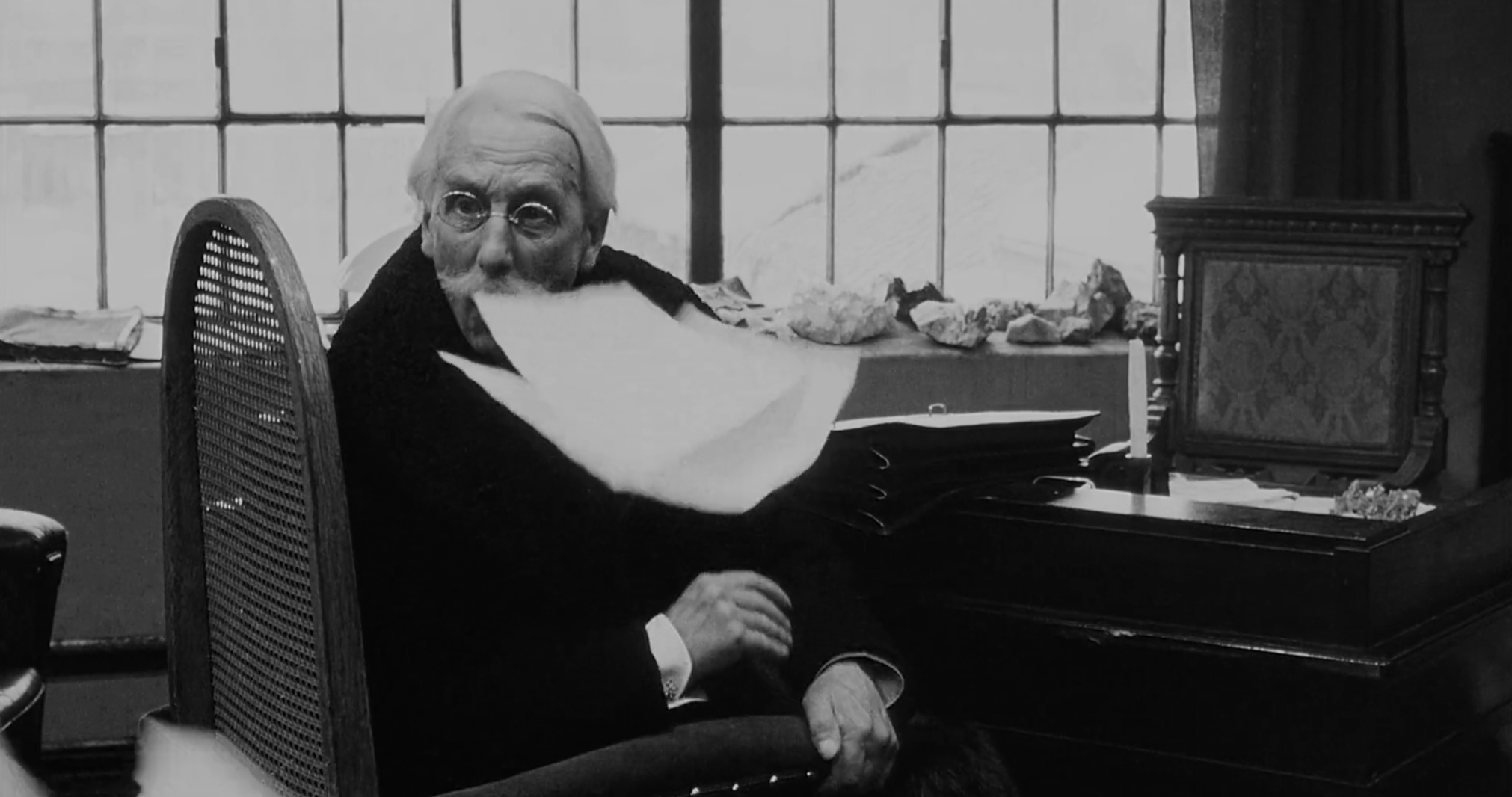

Avvicinandosi alla scrivania sulla sedia a rotelle, prende una pila di fogli. "Leggete questi conti! In mezza giornata ho fatto il lavoro che voi non avete fatto in un mese!"

Going to the desk in his wheelchair, he picks up a stack of papers. “Read these accounts! In half a day, I did more work than you have done in a month!”

"In quattro settimane non abbiamo guadagnato un centesimo. I nostri clienti stanno ordinando la loro merce altrove. È arrivato il momento dell’azione! Niente più scuse!"

“In four weeks, we haven’t made a cent. Our customers are ordering their goods elsewhere. The time has come for action! No more excuses!”

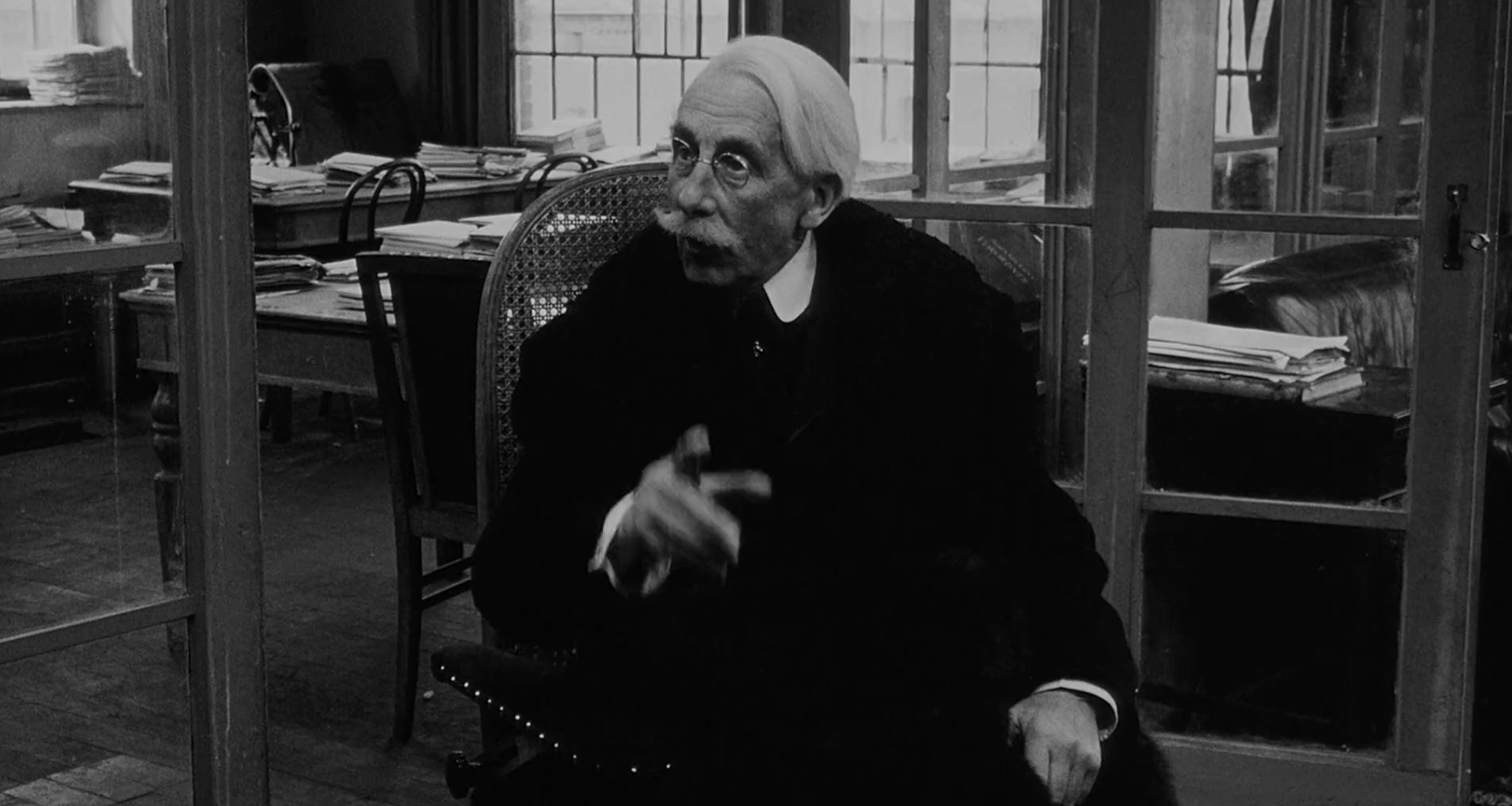

Getta i fogli in aria con disgusto. Mentre i suoi subordinati si inginocchiano per raccoglierli, Baudet spiega: "Abbiamo fatto dei passi in diverse direzioni. L’unione tessile ha persino votato per...".

He tosses the papers into the air in disgust. As his subordinates kneel down to pick them up, Baudet explains, “We’ve taken steps in several directions. The textile union even voted to –”

"Me ne frego!" lo interrompe il proprietario. Gli uomini sono di nuovo in piedi, con le carte in mano. "Quella gente non molla finché c’è quell’agitatore che li dirige”.

Si rivolge a Baudet. "Lei! Glielo dico io come può meritarsi lo stipendio: vada alla polizia. Perché non si rispettano le leggi di pubblica sicurezza? Quel professore ha dei precedenti. Che cosa si aspetta ad arrestarlo?"

Conclude: "Altrimenti dovremo concedere agli operai tutto ciò che vogliono".

“I don’t give a shit!” the owner interrupts him. The men are standing again, papers in their hands. “These people won’t give up as long as that agitator is leading them.”

He turns to Baudet. “You! I’ll tell you how you can earn your salary: go to the police! Why are public safety laws not being respected? That professor has a record. What are they waiting for to arrest him?”

He concludes, “Otherwise we’ll have to give the workers everything they want.”

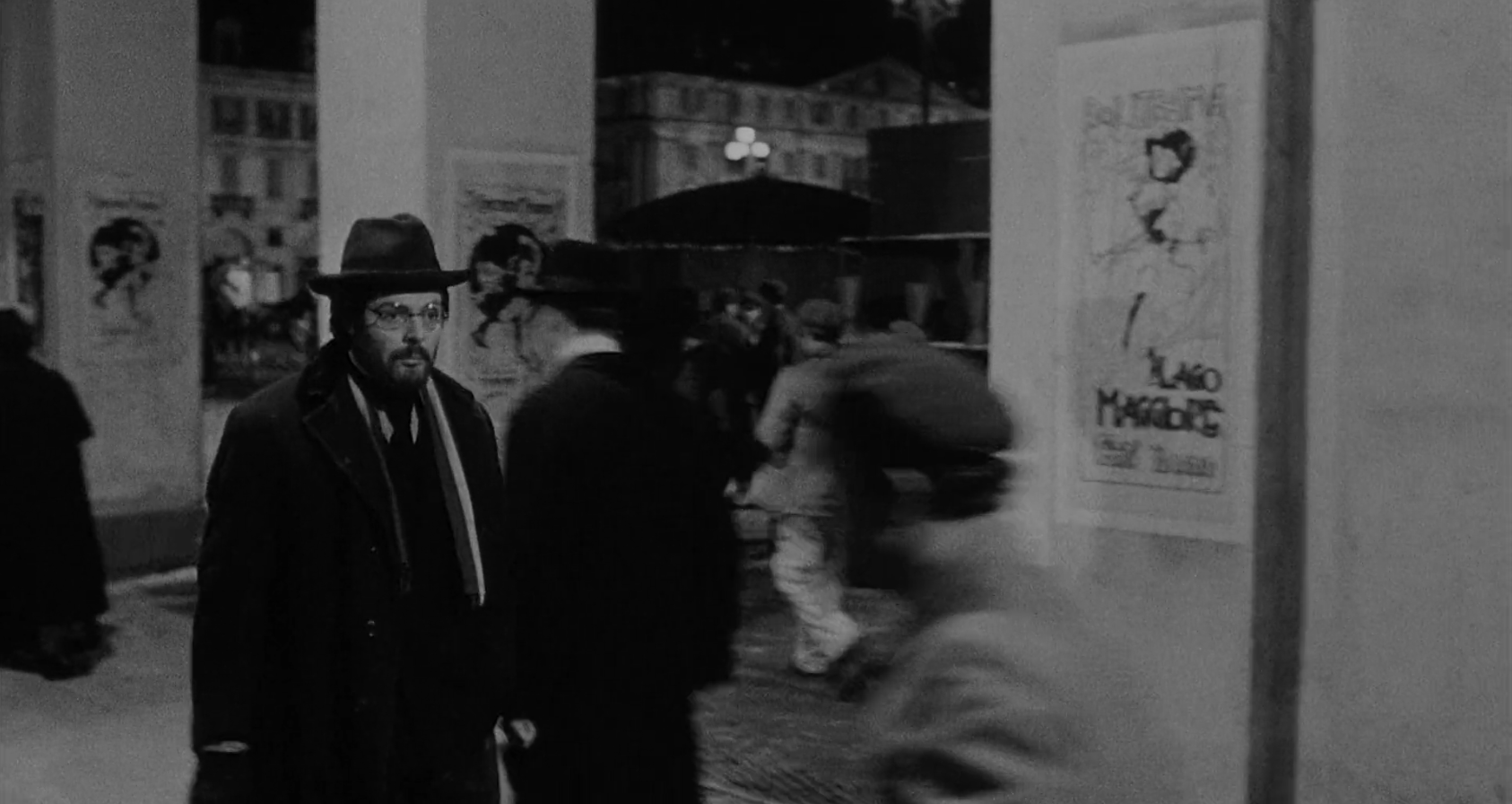

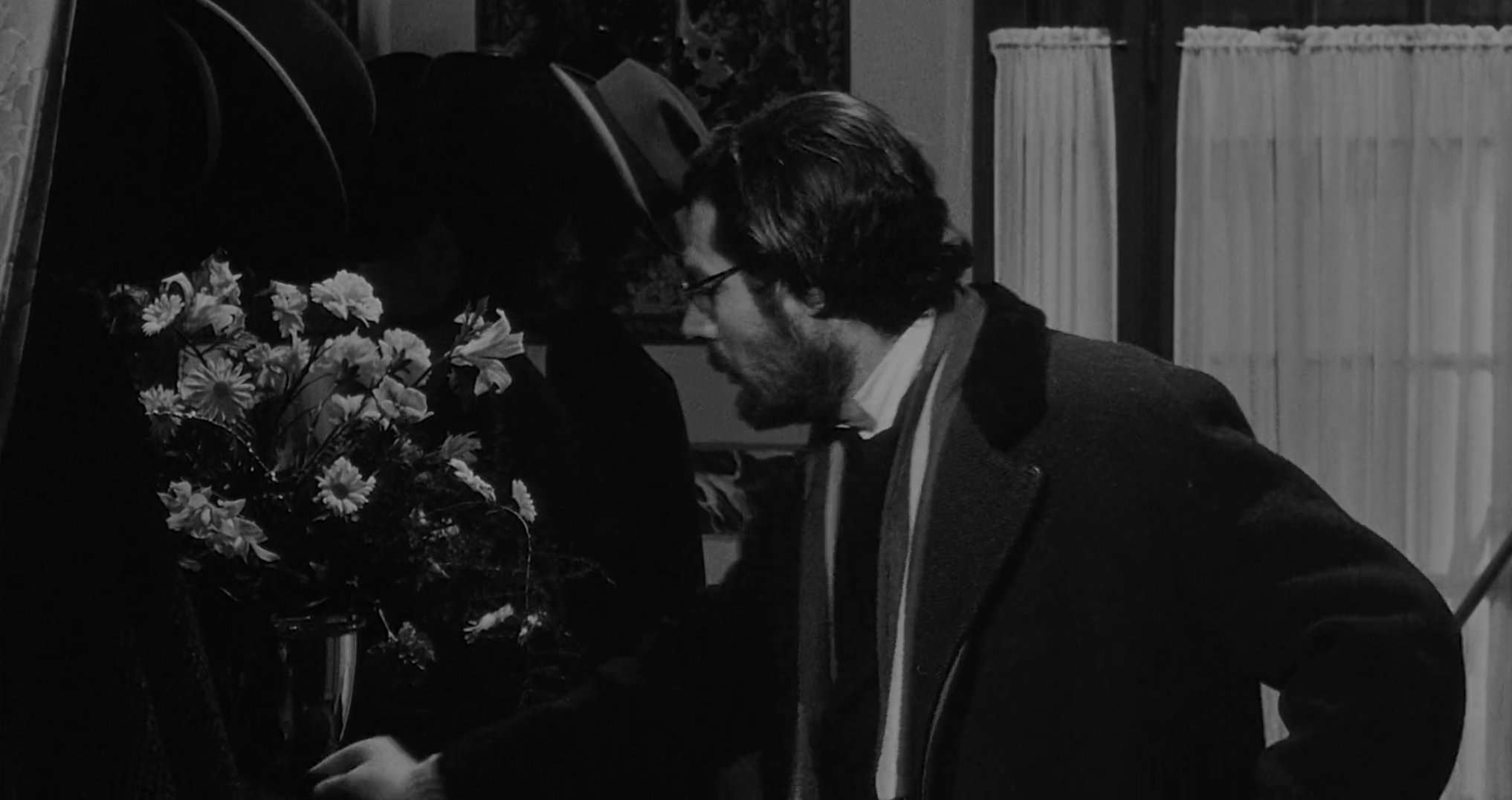

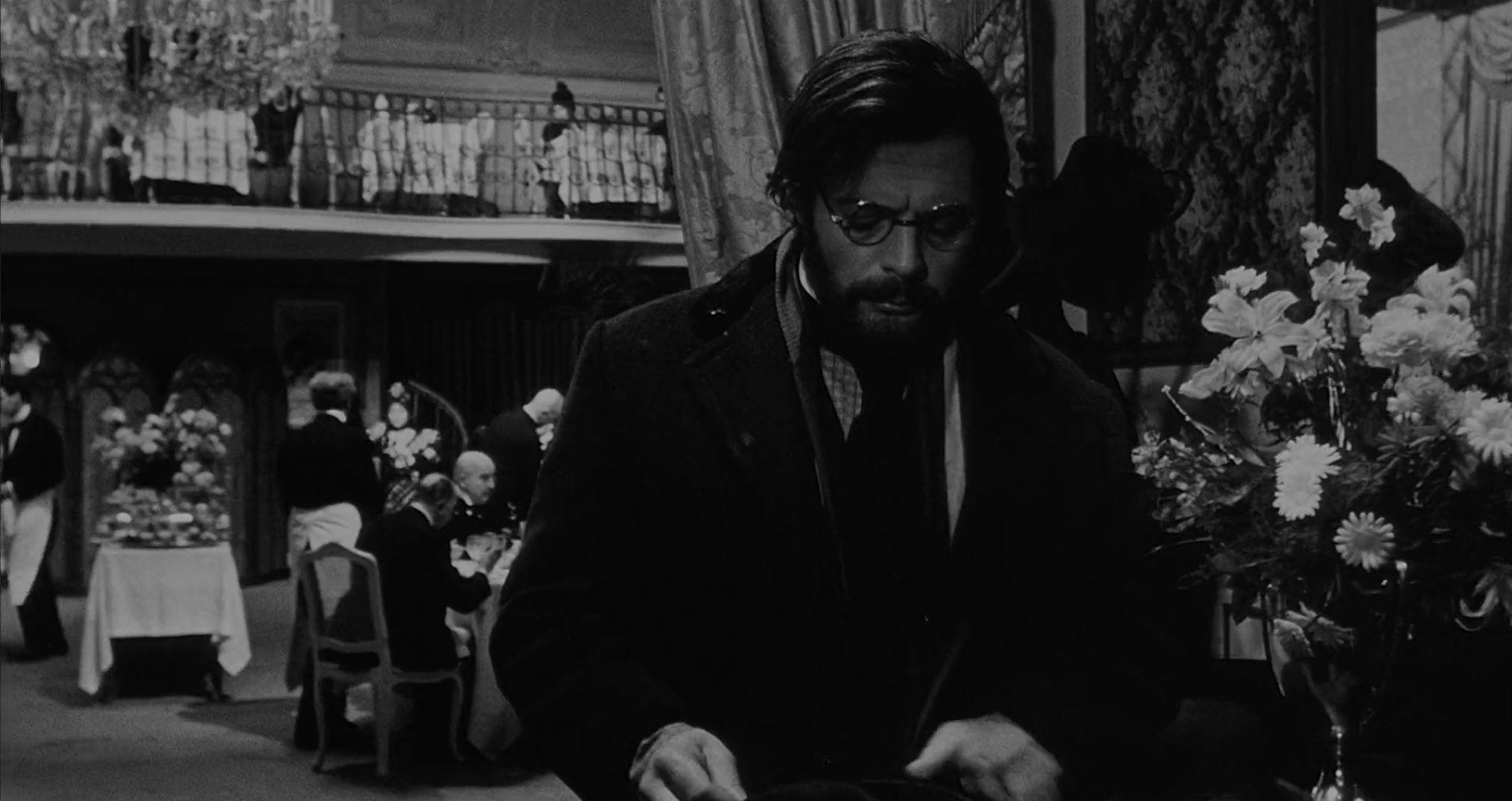

Il professore cammina in piazza. Si ferma davanti alla vetrina di un ristorante e osserva il ricco buffet.

The Professor is walking in the piazza. He stops at a restaurant window and gazes at the lavish display of food.

Entrando nel ristorante, si toglie il cappello e lo mette vicino a un vaso di fiori.

Entering the restaurant, he takes off his hat and sets it next to a vase of flowers.

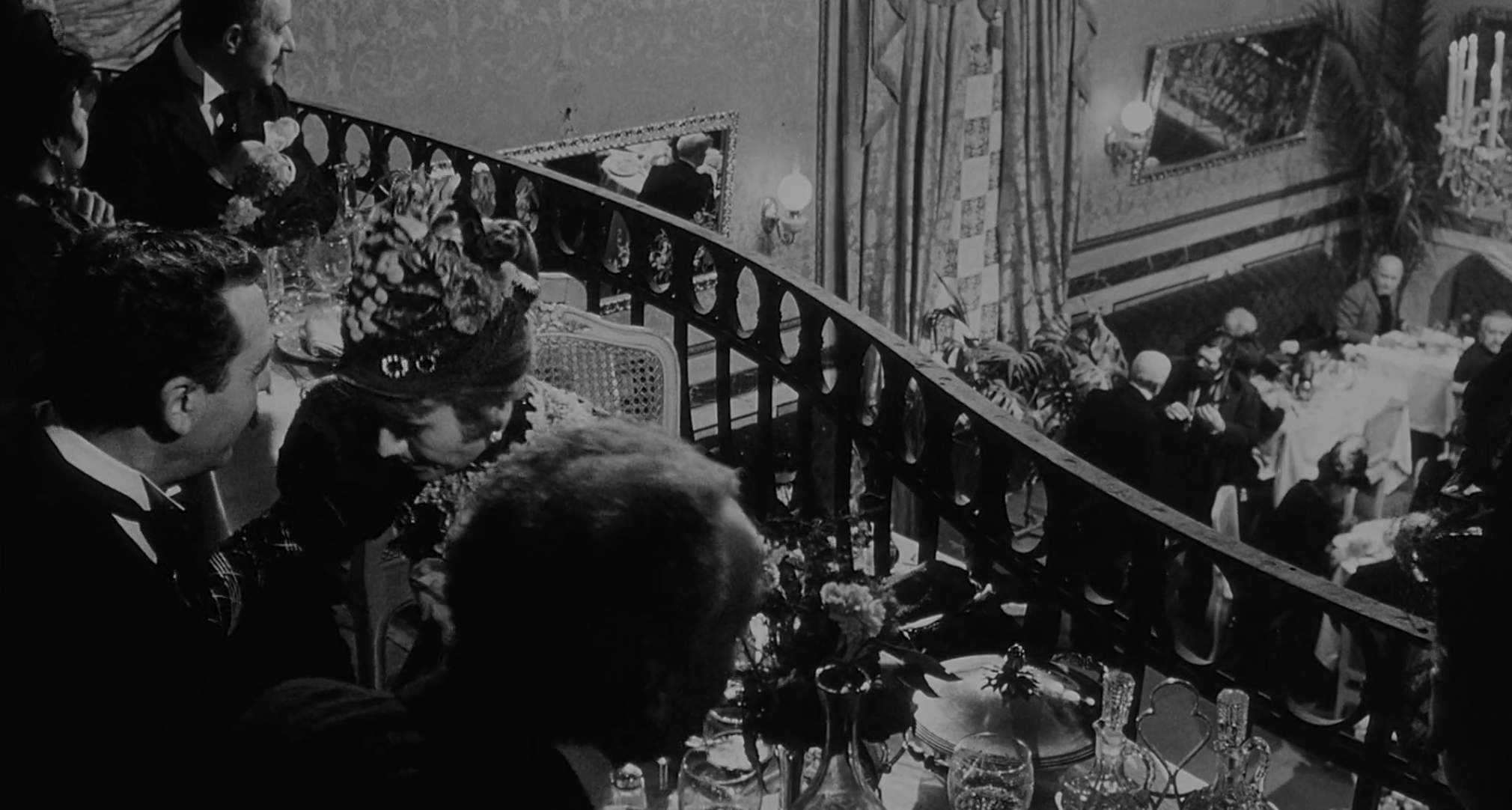

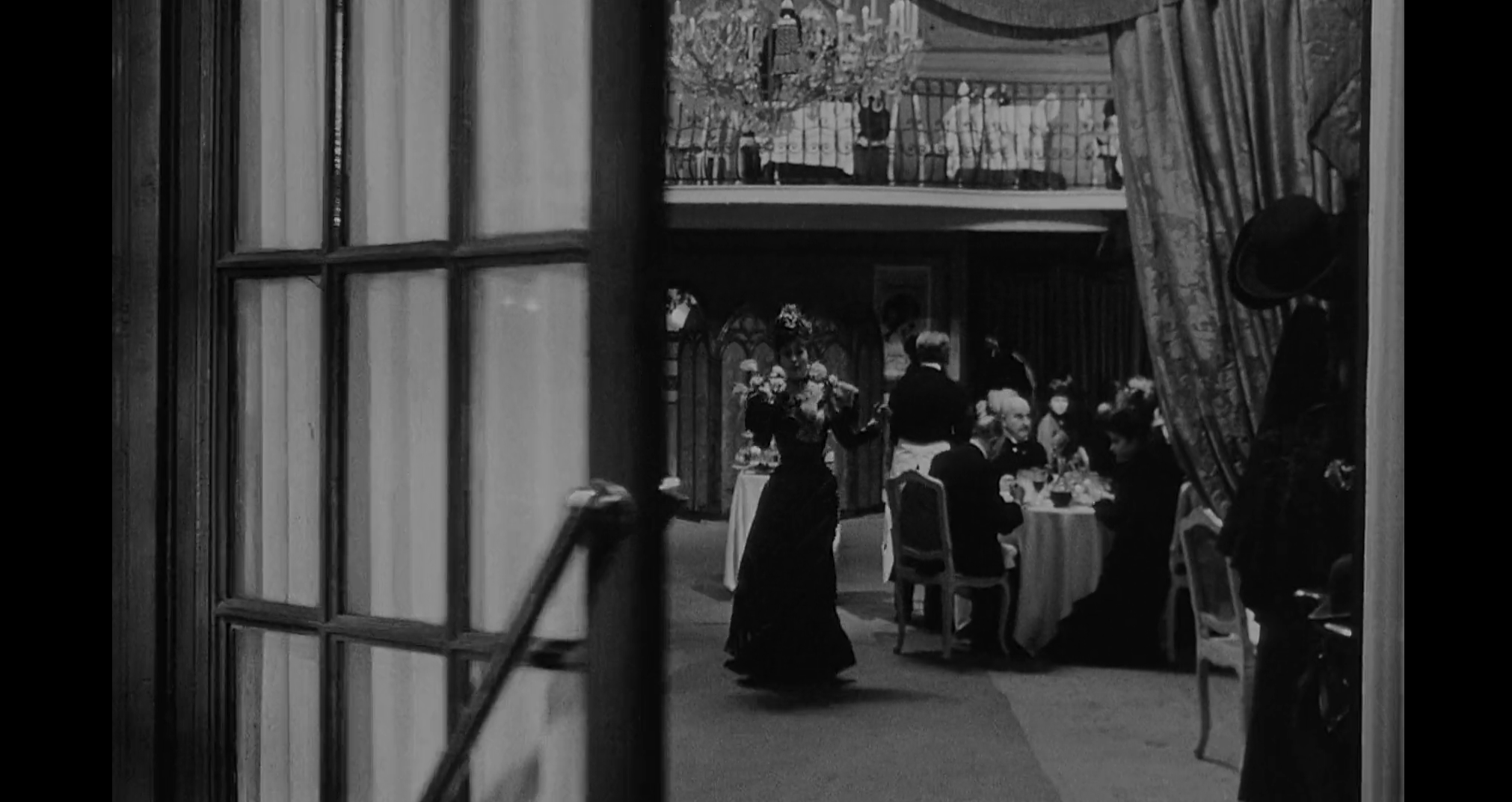

All'interno, clienti vestiti elegantemente parlano tranquillamente sotto un lampadario. Su un balcone, Niobe cena con una collega e due clienti.

Inside, elegantly dressed customers talk quietly under a chandelier. On a balcony, Niobe dines with a colleague and two customers.

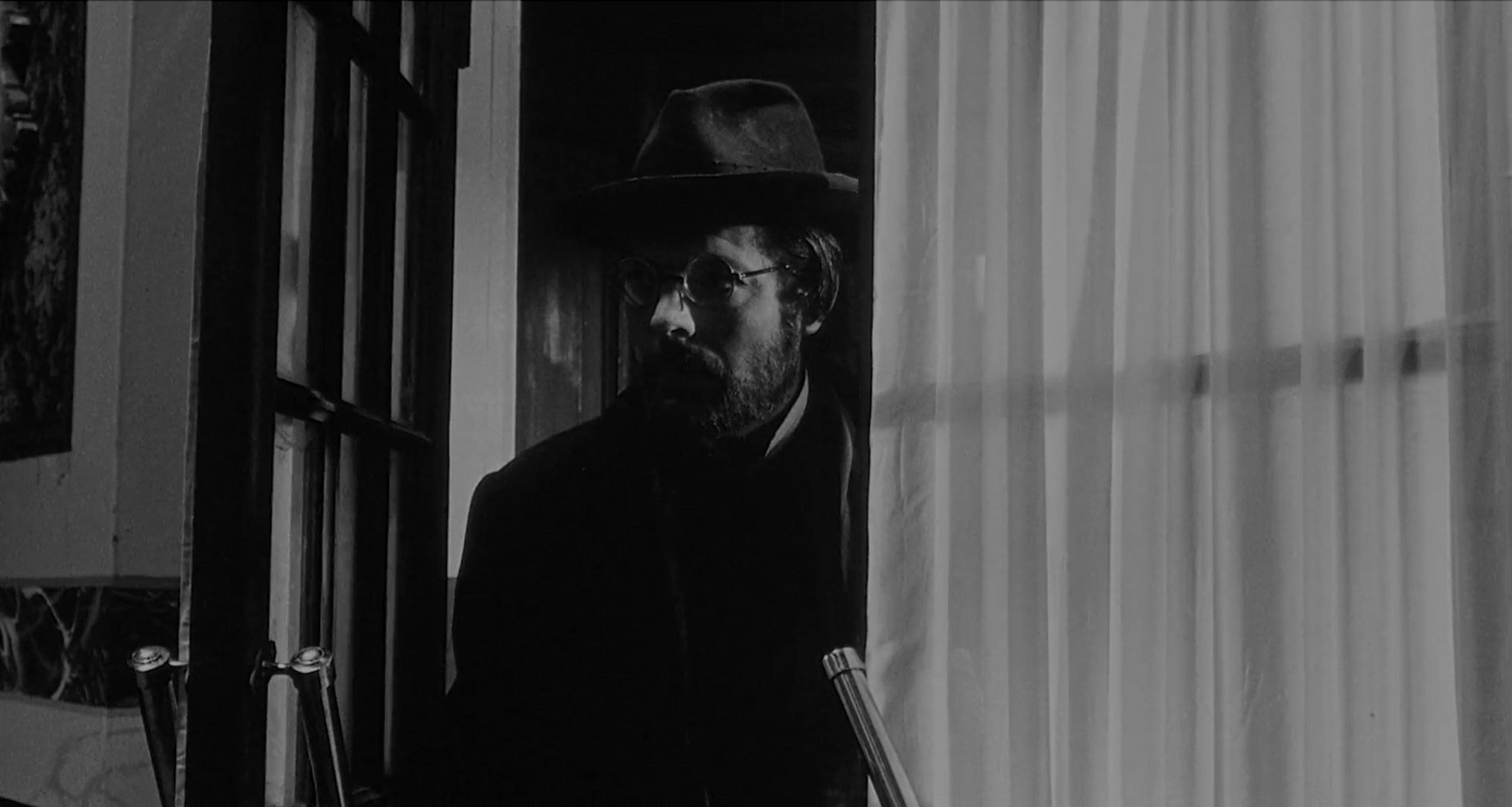

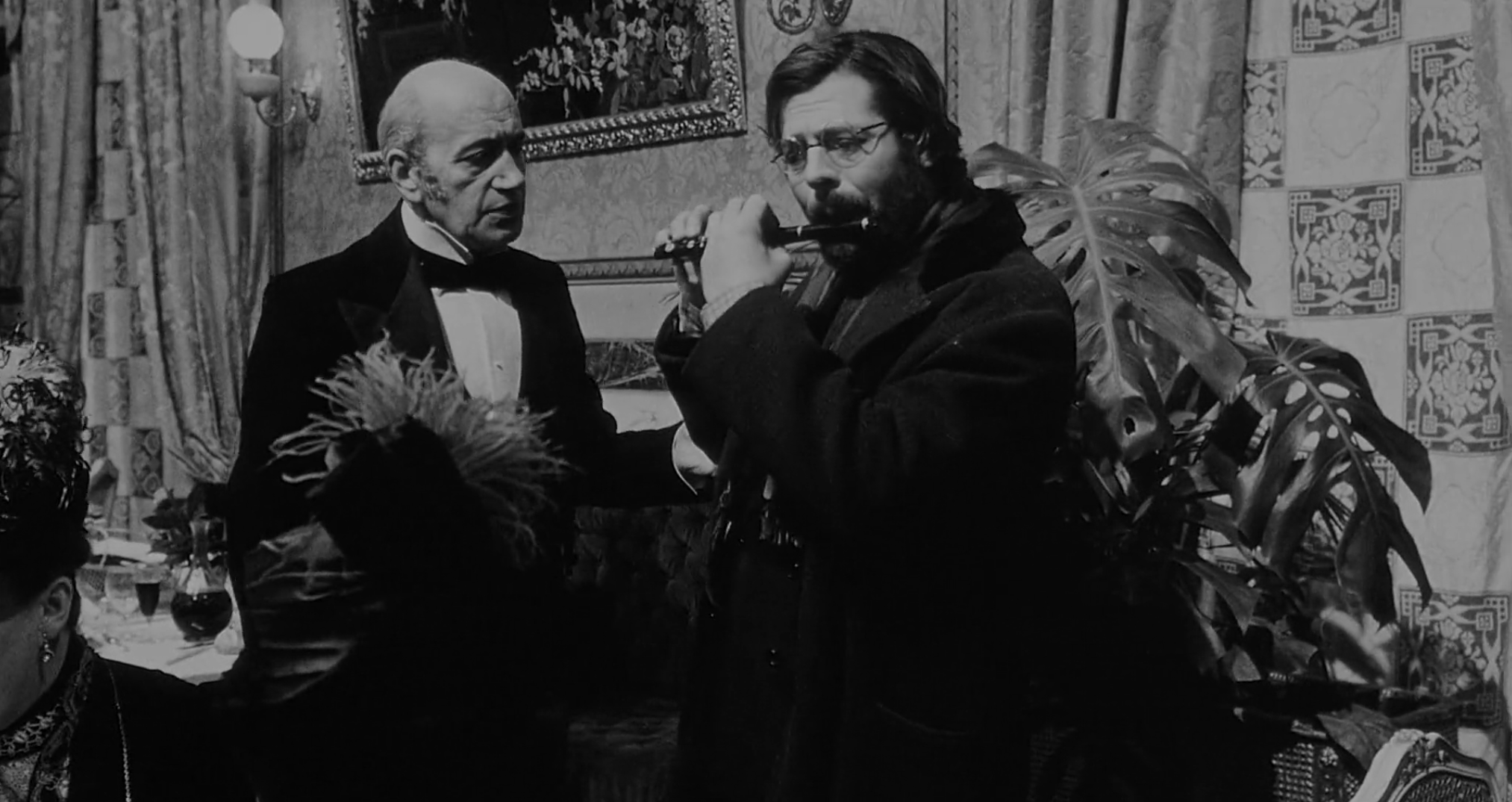

Trovando un posto a lato della stanza, il professore tira fuori il suo ottavino e suona una melodia tranquilla, uno dei temi del film.

Finding a spot at the side of the room, the Professor takes out his piccolo and plays a quiet melody, one of the film’s themes.

Sul balcone, uno degli uomini chiede: "Chi è?"

"Io lo conosco!" risponde Niobe sorpresa.

On the balcony, one of the men asks, “Who’s that?”

“I know him!” Niobe answers in surprise.

La melodia del professore infastidisce i clienti. Un cameriere si avvicina: "Non si può, sa. È proibito".

Niobe si rivolge al suo compagno. "Dammi qualcosa per quello lì!" Gli toglie un po’ di soldi dalla tasca.

The Professor’s tune is annoying the customers. A waiter approaches: “You can’t, you know. It’s prohibited.”

Niobe turns to her companion. “Give me something for him!” She takes some money right out of his pocket.

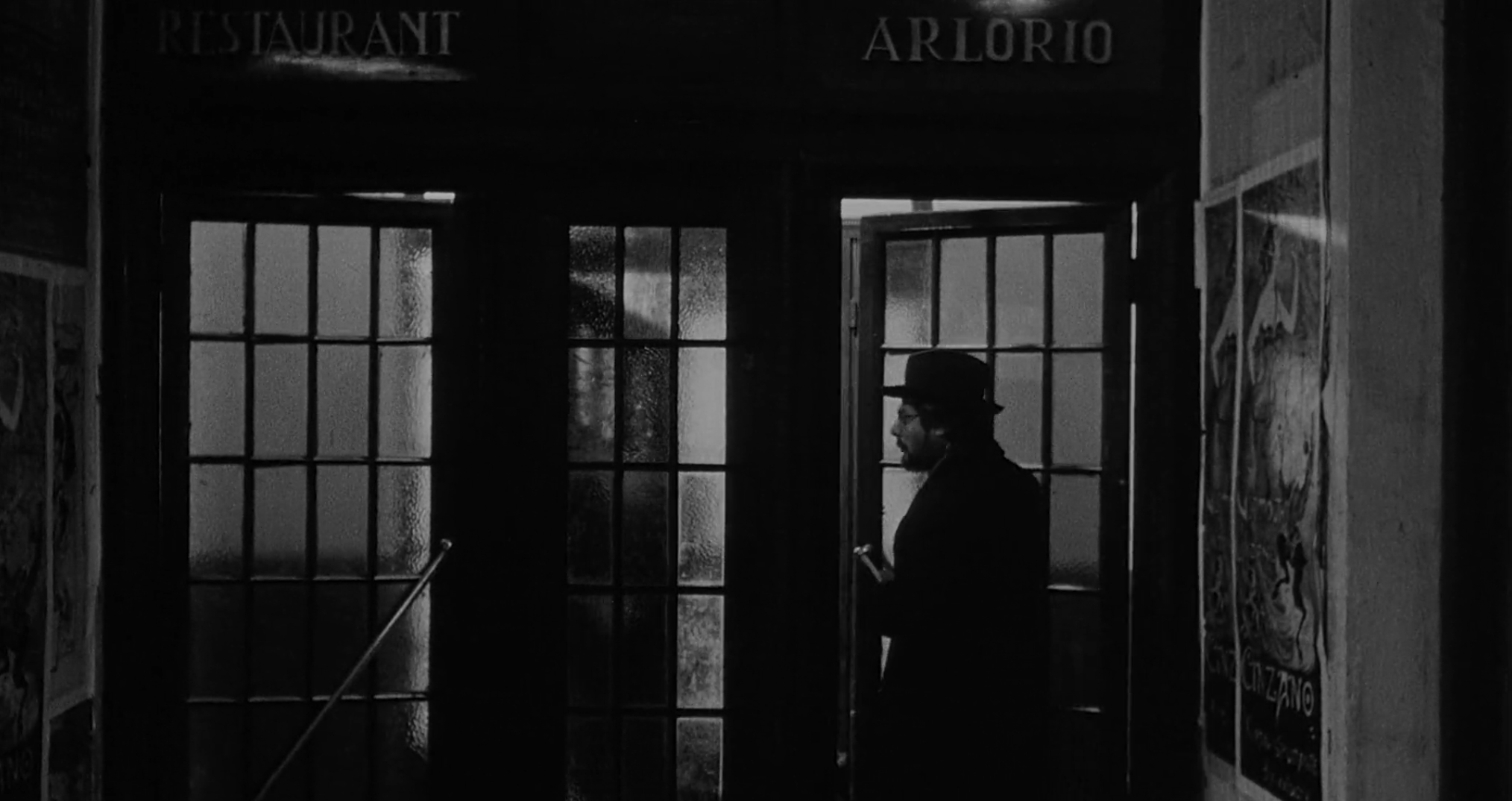

Il cameriere dice: "Se ne vada per piacere". Il professore annuisce, mette via il suo strumento ed esce, mentre i clienti lo fissano. Prende il suo cappello.

Says the waiter, “Please leave.” The Professor nods, puts away his instrument, and walks out, as the customers stare. He picks up his hat.

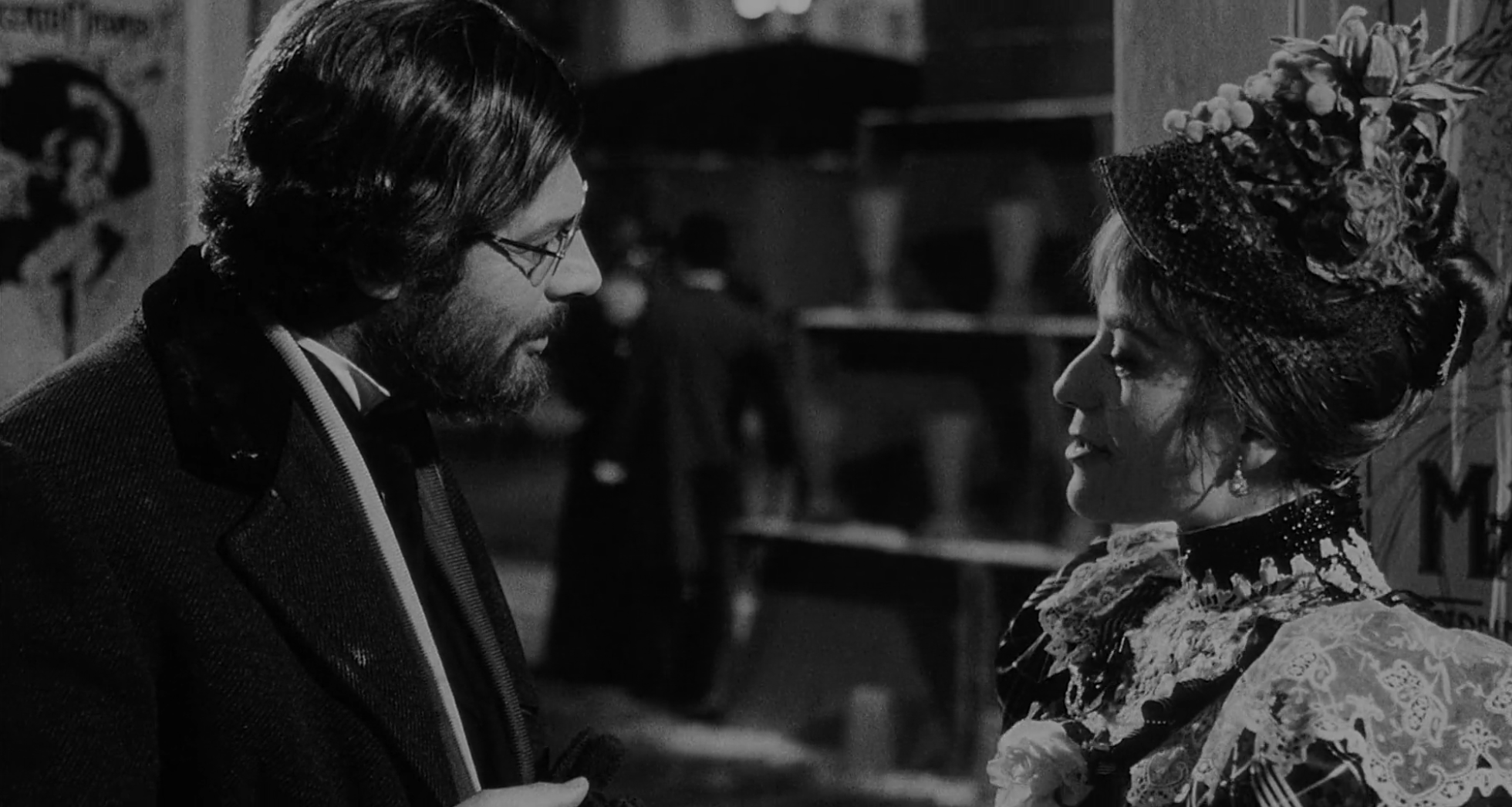

Niobe lo chiama – "Signore! Signore!" – ma lui se ne va senza sentirla. Lei lo segue fuori, agitando i soldi in aria. “Ehi, aspetti!”

Niobe calls him – “Sir! Sir!” – but he leaves without hearing her. She follows him outside, waving the money in the air. “Hey, wait!”

Raggiungendolo, lei gli mostra i soldi. "Tenga!"

"Grazie!"

"Lei è della fabbrica?"

"No, io sono professore".

Catching up, she shows him the money. “Here!”

“Thank you!”

“Are you from the factory?”

“No, I’m a professor.”

"Allora mi deve scusare per averle dato…" dice lei, imbarazzata. Ma lui spiega che stava suonando proprio nella speranza di ricevere delle donazioni. Mentre parlano, scoprono di avere qualcosa in comune: entrambi hanno cambiato professione – lui ha smesso di insegnare, lei di lavorare in filanda – e ora fanno qualcosa che non è molto apprezzato.

“Oh, then excuse me for giving you…” she says, embarrassed. But he explains that he was in fact playing in the hope of donations. As they talk, they find they have something in common: they have both changed their professions – he quit teaching, she quit working in the textile mill – and now do something that is not highly regarded.

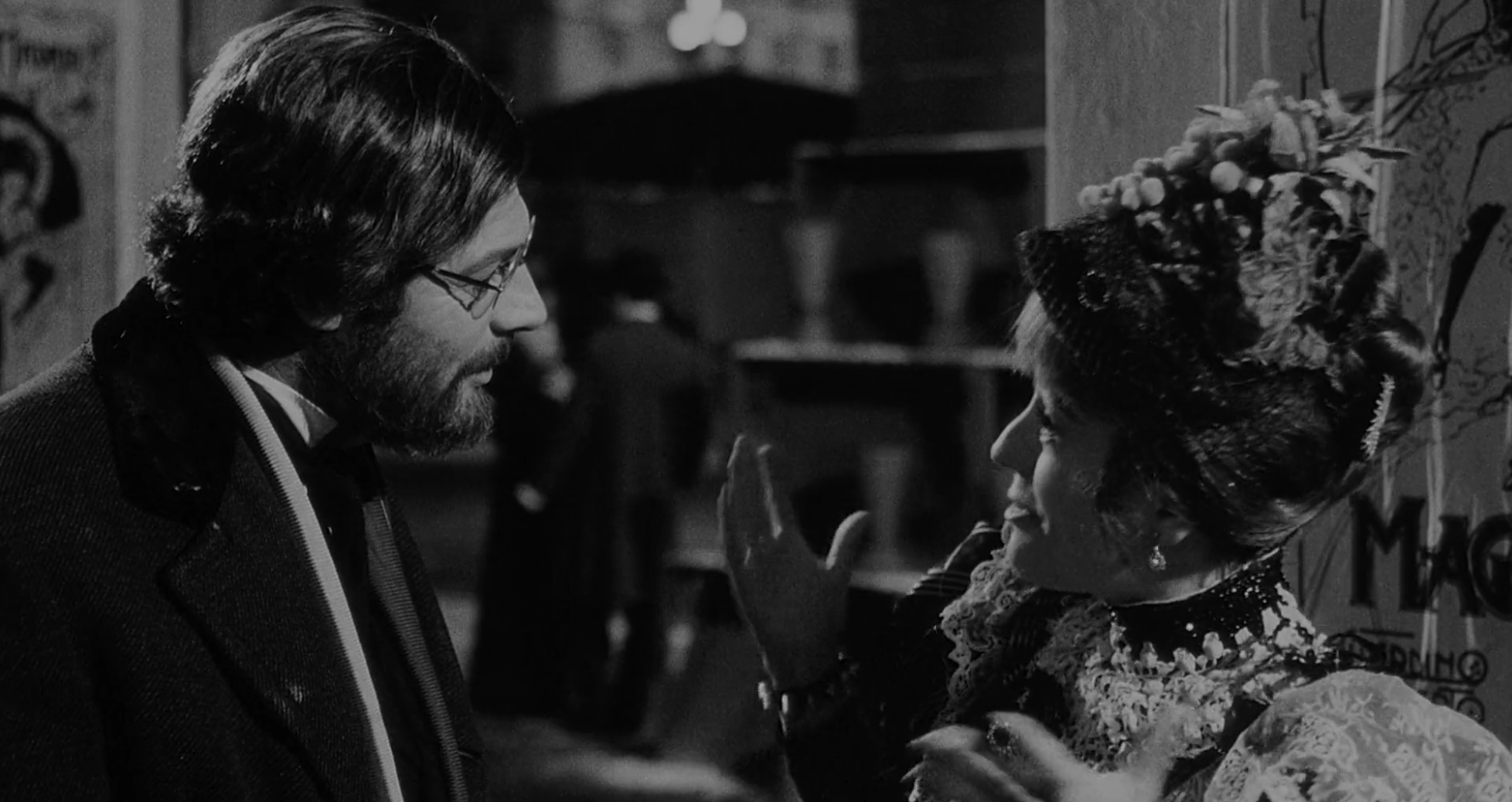

"E perché si è messo in mezzo a questi guai?" chiede lei.

"Per egoismo".

"Non capisco".

"Perché mi piace e quando una cosa piace non è un sacrificio".

“And why have you gotten involved in these troubles?” she asks.

“Out of selfishness.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Because I like it and when you like something it’s not a sacrifice.”

Continua: "E anche perché vorrei che un giorno una ragazza come lei..."

"Allora?"

"...non sarà costretta a fare come ha fatto lei".

He goes on, “And because I would like it if one day a girl like you…”

“Well?”

“...won’t be forced to do as you have done.”

Lei si acciglia e torna dentro. Il professore torna da solo a casa di Raoul, ancora affamato.

She frowns and returns inside. The Professor heads back alone to Raoul’s place, still hungry.

FINE PARTE 8

Ecco the link to Parte 9 of this cineracconto! Subscribe to receive a weekly email newsletter with links to all our new posts.