Regia / Director: Mario Monicelli, 1963

Camminando lungo il fiume, Omero arriva a una capanna dove siede una ragazza che bada a un piccolo fuoco.

Walking along the river, Omero comes to a shack where a girl sits, tending a small fire.

Lui chiede: "La famiglia Arrò vive qui?" Lei alza lo sguardo. "Sì. Perché?"

He asks, “Does the Arròfamily live here?” She looks up. “Yes. Why?”

"Sono uno della fabbrica. Abbiamo fatto una colletta. È poco perché c'è lo sciopero".

“I’m from the factory. We took up a collection. It’s not much because we’re on strike.”

Lei prende la borsa e corre in casa. "Mamma!"

"Cosa c'è?" chiede sua madre da fuori campo.

"Hanno portato dei soldi!"

She takes the bag and runs into the house. “Mama!”

“What is it?” her mother asks from off-screen.

“They brought money!”

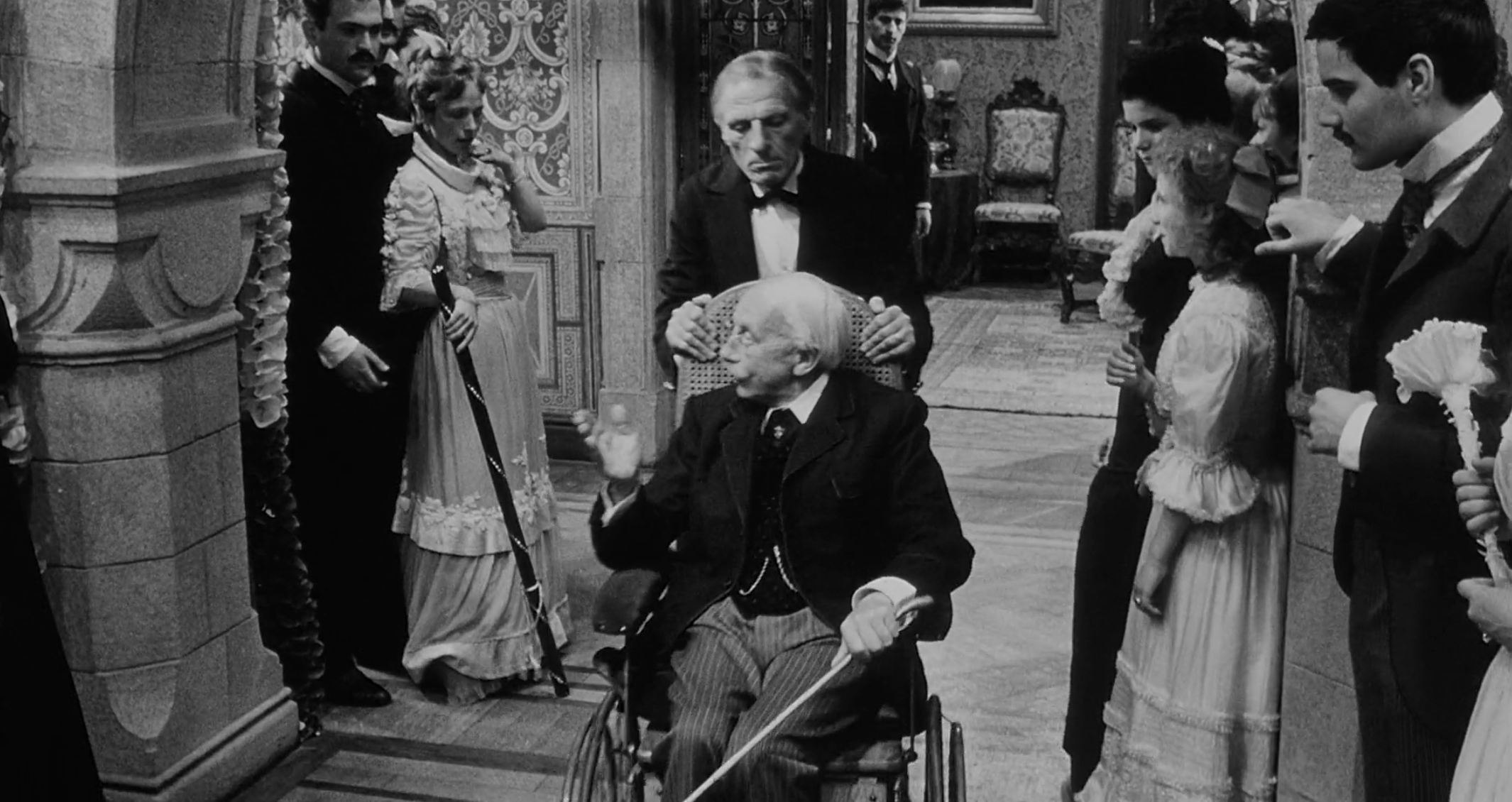

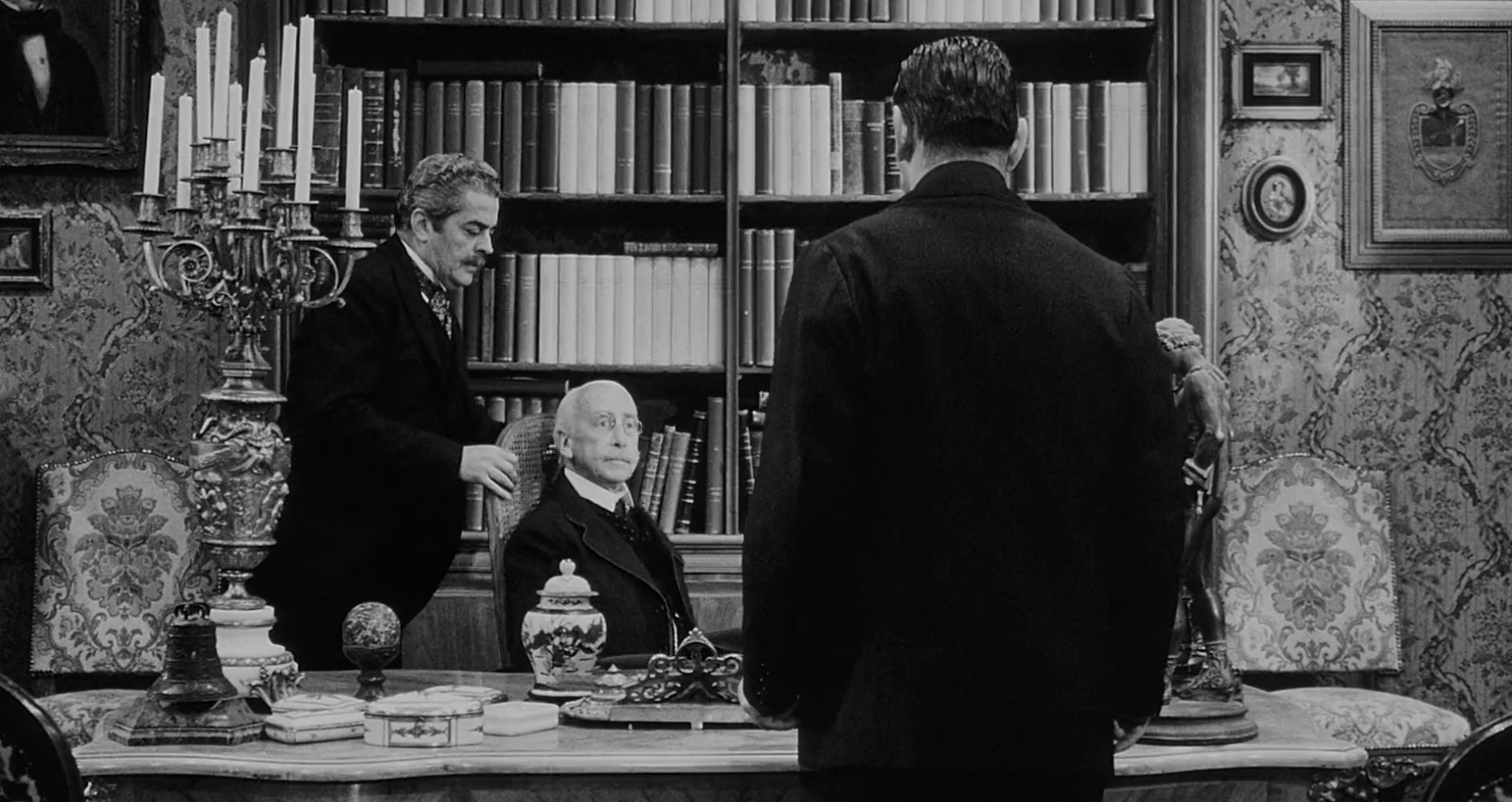

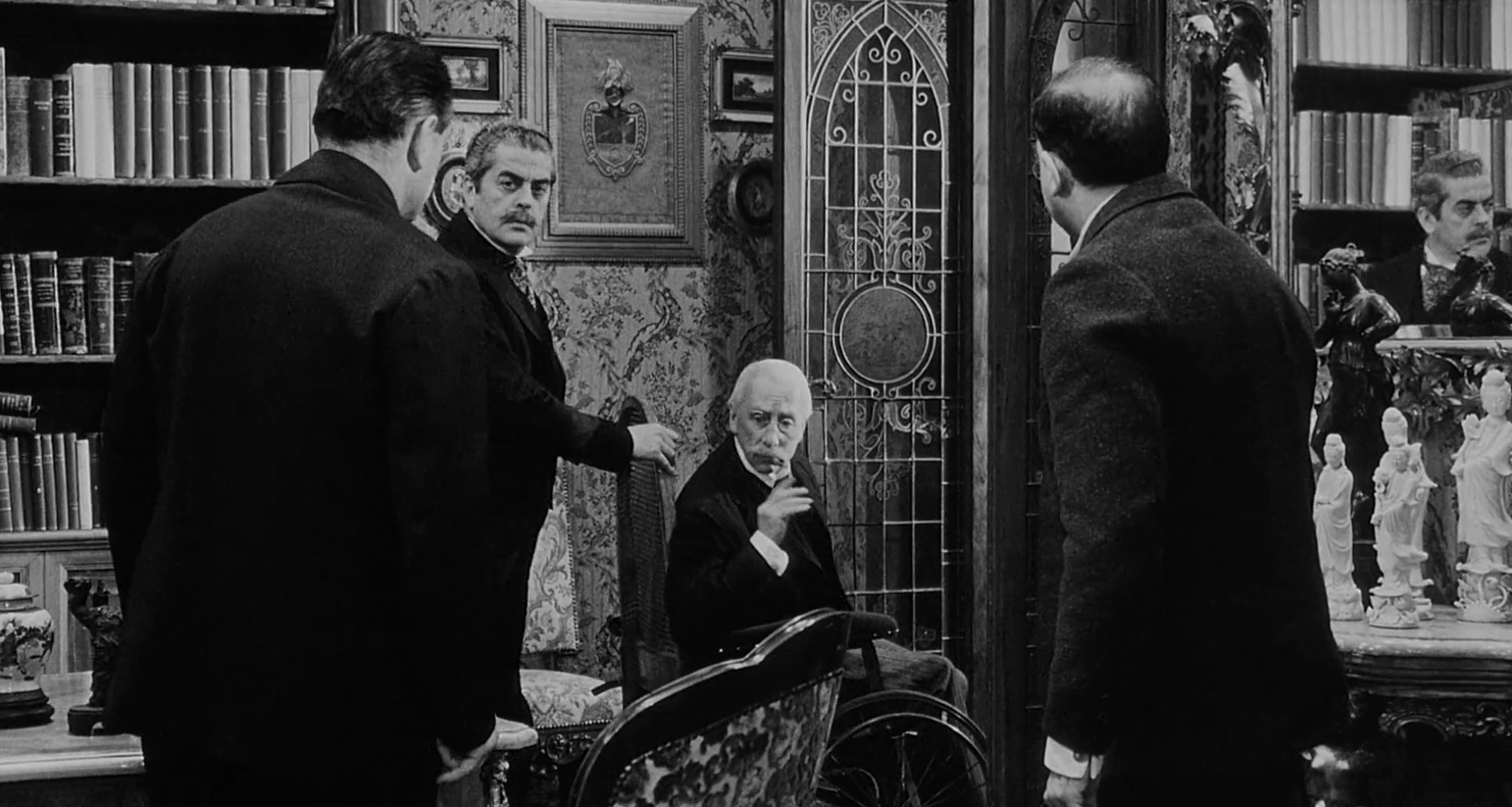

La scena si sposta su una festa dove giovani donne giocano e ridono. Una porta si apre, rivelando un uomo dai capelli bianchi su una sedia a rotelle: Luigi, il proprietario della fabbrica. Urla: "Buondì a tutti!"

The scene shifts to a party where young women are playing games and laughing. A door opens, revealing a white-haired man in a wheelchair: Luigi, the factory owner. He calls out, “Good day, everyone!”

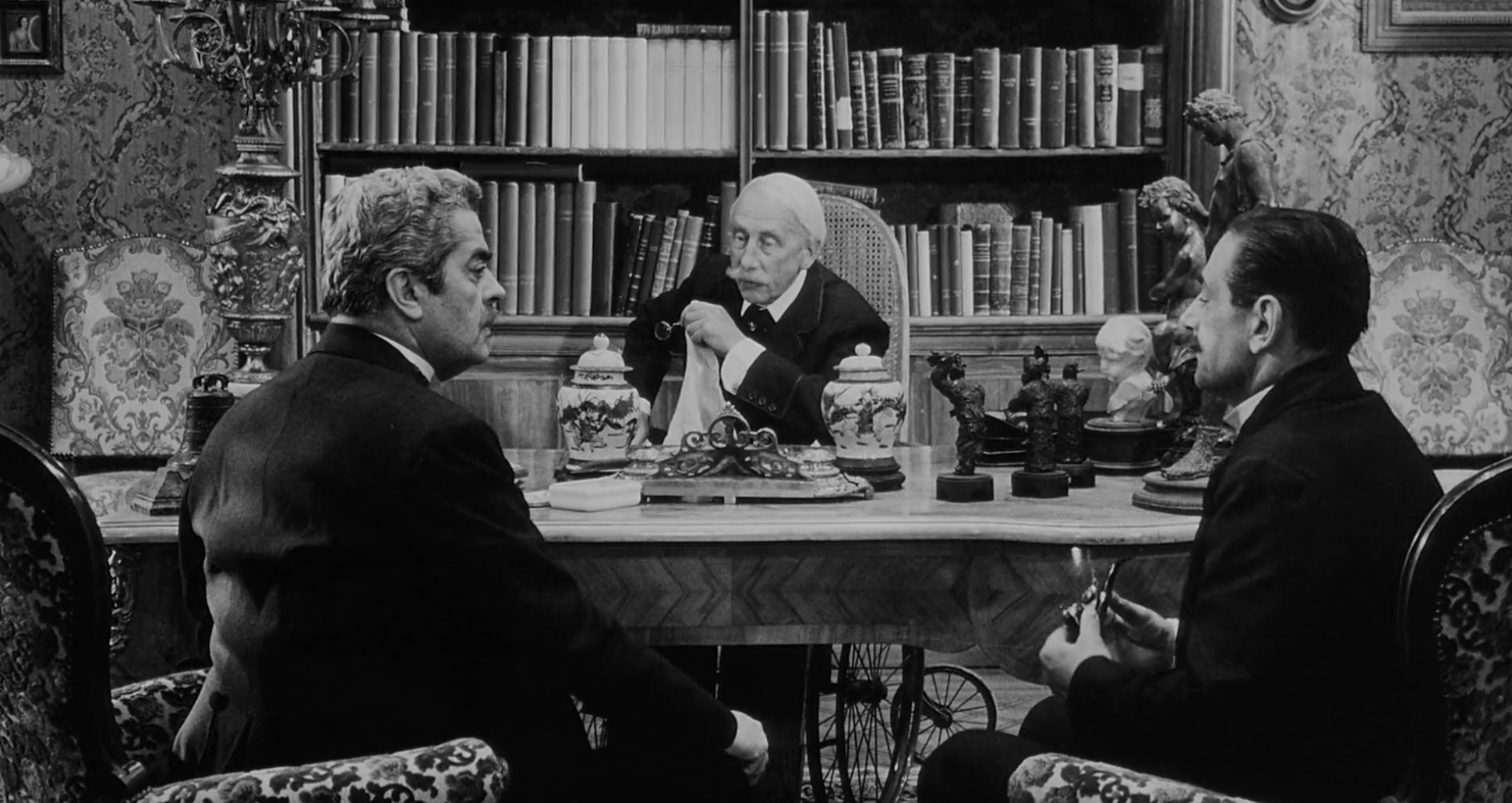

Passa direttamente in un ufficio dove lo aspettano tre dirigenti: tra loro suo nipote e Baudet.

Il nipote dice: "Stavo dicendo, zio, che possiamo ritenere che gli operai non potranno resistere a lungo. Insomma..."

He passes straight through to an office where three managers await him: among them his nephew and Baudet.

The nephew says, “We were saying, Uncle, that we can assume that the workers won’t be able to hold out much longer. So –”

Il proprietario lo interrompe. "Con la fabbrica ferma e le consegne in ritardo, stiamo perdendo soldi! Quella gente ce la fa in mille modi! C’è chi li aiuta con le collette, nelle caserme dell'esercito e anche nei nostri centri di carità!“

The owner cuts him off. “With the factory at a standstill and our deliveries behind, we’re losing money! Those people get by in a thousand ways! There are people who help them with collections, in the army barracks and even in our charities!”

"Non sono nostri. Sono opere pie!" protesta il nipote.

Il proprietario ribatte: "Sì, l’opera pia la faccio io con te da vent'anni!

“They are not ours. They are religious charities!” the nephew protests.

The owner counters, “You’ve been living off my charity for twenty years!”

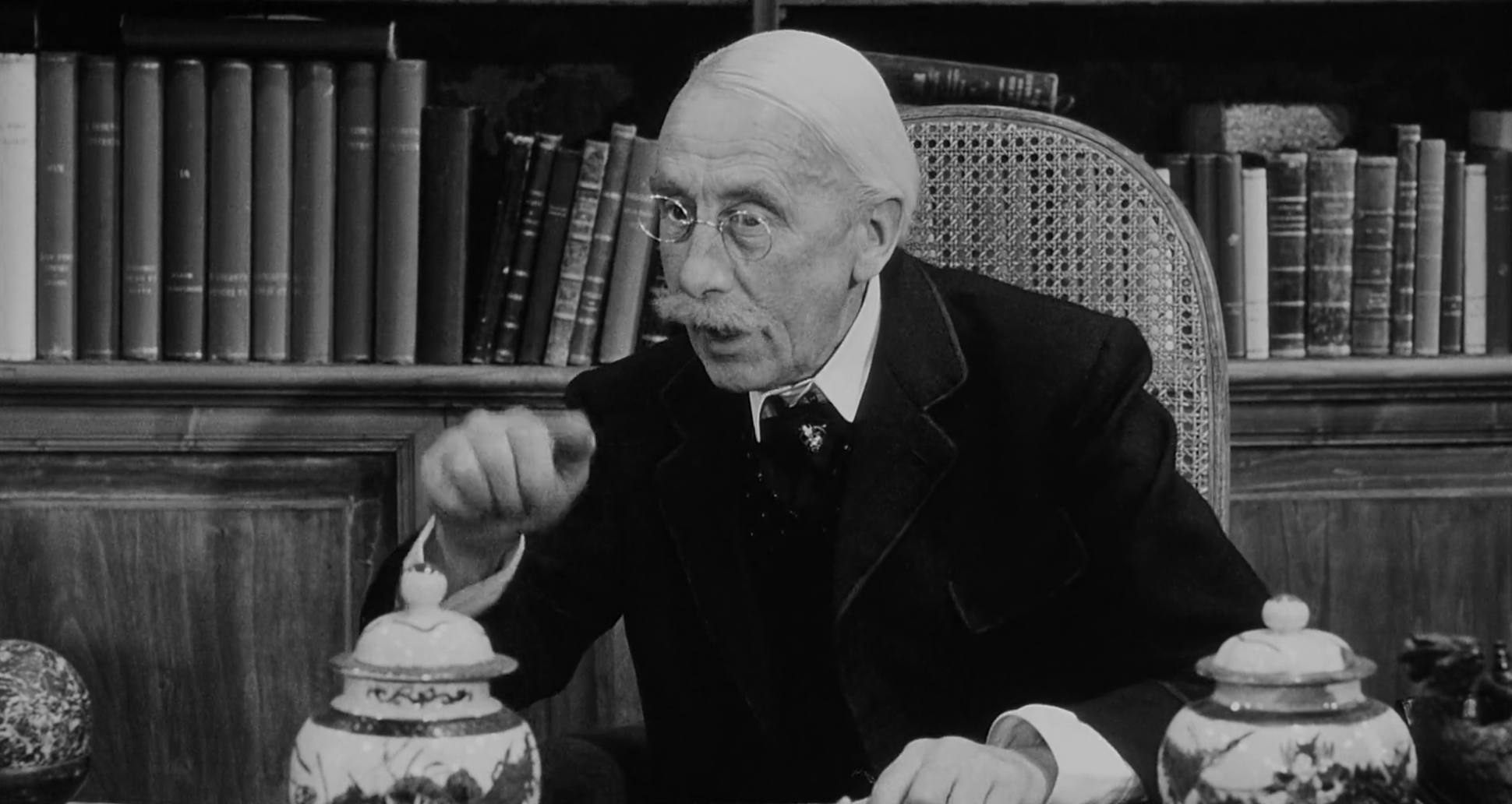

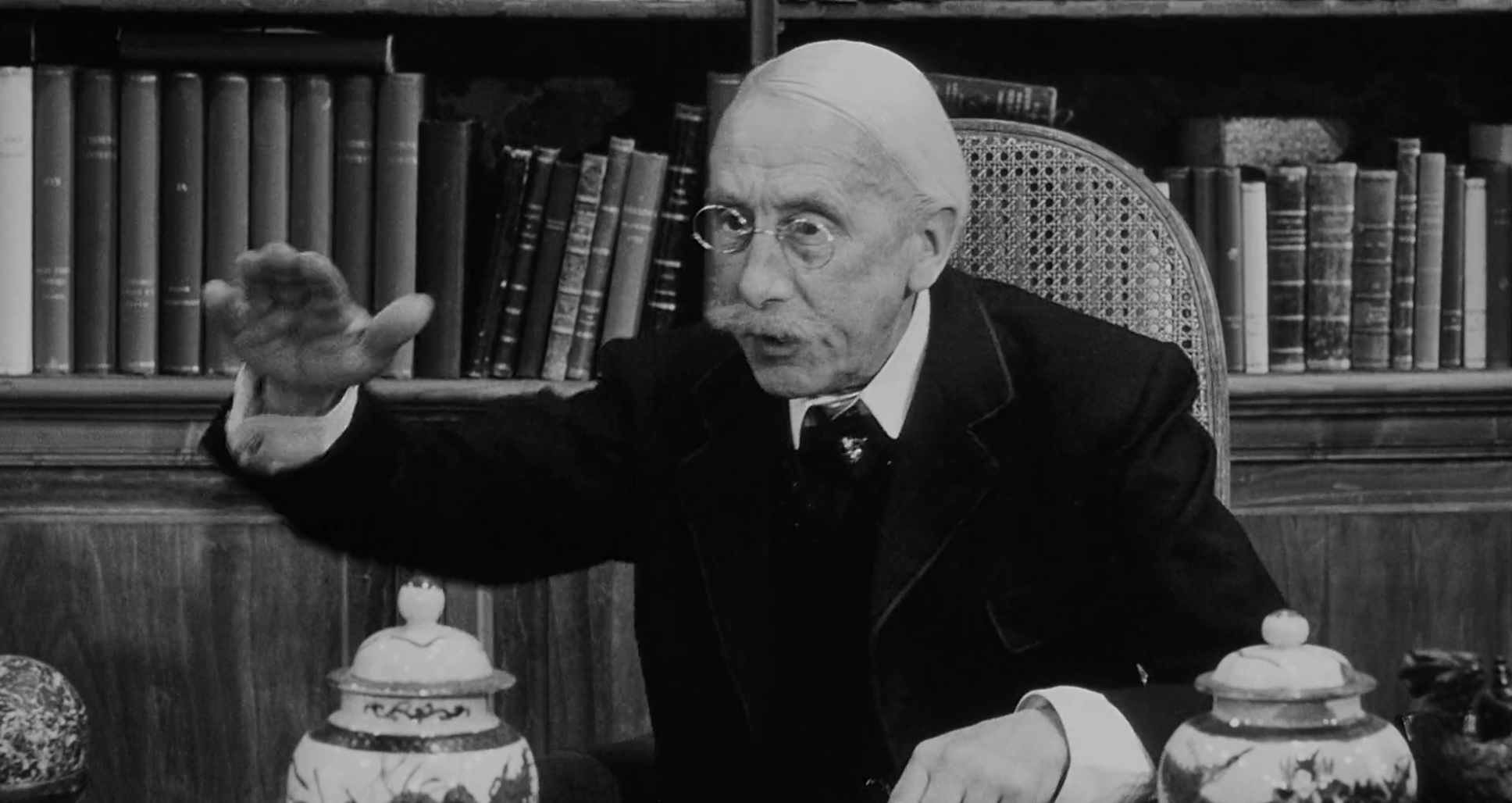

"È arrivata l’ora di svegliarvi, marmotte!" – dice con rabbia – "Se loro hanno degli amici, li abbiamo anche noi, e molto più forti. Tagliamogli i viveri e chiudiamogli tutte le strade. Quando avranno capito chi è che suona la musica" – batte sulla scrivania con le nocche – "allora li chiamiamo e vedrete come diventano più ragionevoli”.

“The time has come to wake up, groundhogs!” he says angrily. “If they have friends, so do we – and much more powerful. Let’s cut off their supplies and block all the ways they have of getting by. When they understand who’s calling the tune” – he raps on the desk with his knuckles –“then we’ll call them and you’ll see how reasonable they become.”

Poi invita Baudet a unirsi a loro alla festa.

"Grazie!" risponde Baudet.

Ma poi il proprietario guarda l'uomo dalla testa ai piedi. Ripensandoci dice: "No, non ha l’abito adatto. Meglio di no".

Baudet si guarda per capire dove ha sbagliato.

Then he invites Baudet to join them at the party.

“Thank you!” Baudet answers.

But then the owner looks the man up and down. Rethinking, he says, “No, you’re not properly dressed. Better not.”

Baudet looks down at himself to see where he went wrong.

Omero si affretta lungo i binari della ferrovia con la figlia di Arrò, Gesummina (Anna Di Silvio). Ha in mano un enorme cesto di vimini.

Omero hurries along the railroad tracks with Arrò’s daughter, Gesummina. He’s holding a huge wicker basket.

"Dove danno il carbone gratis?" chiede lei.

"In un posto che so solamente io. Stai tranquilla".

“Where do they give this free coal?” she asks.

“In a place that only I know. Don’t worry.”

Lungo la strada lei commenta: "Qui non c’è mai il sole!"

Omero risponde: “Allora perché siete qui? Sai come va male il Piemonte da quando ci siete voi siciliani?”

“Mio padre dice che è la Sicilia che va male da quando siete arrivati voi piemontesi!”*

*L'unificazione dell'Italia era appena avvenuta nel 1861, dopo l'annessione della Sicilia da parte del Piemonte. Negli anni seguenti, la resistenza locale, chiamata “brigantaggio”, ha combattuto – invano – contro l'esercito piemontese.

Along the way she comments: “The sun never shines here!”

Omero answers: “So why are you here? Don’t you know how bad Piemonte has been since you Sicilians have come?”

“My dad says it’s Sicily that’s going bad since you Piedmontese arrived!”*

*The unification of Italy had just taken place in 1861 with the annexation of Sicily by Piedmont. In the following years, the local resistance, called “brigandage,” fought – in vain – against the Piedmontese army.

Improvvisamente sentono un grido. "Occhio al carbone!"

Un'alta staccionata di legno attraversa l'immagine: in cima, gli uomini gettano il carbone alle donne che aspettano sotto.

Suddenly they hear a shout. “Look out for the coal!”

A tall wooden fence curves across the image: at the top, men throw coal down to women waiting below.

"Meno male che era un posto che sapevi solo tu!" – dice Gesummina –"Guarda quanta gente c'è!"

Omero alza le spalle. “Boh!”

"Good thing it was a place only you knew about!" says Gesummina. "Look how many people there are!"

Omero shrugs. “I don’t know!”

Tra la folla, Adele chiede: "Il mio papà è dall'altra parte?"

In the crowd, Adele asks, “Is my dad on the other side?

"Attenzione!" urla una voce, e una grande massa nera vola oltre il recinto.

“Look out!” a voice calls out, and a great black mass sails over the fence.

"Eccolo il mio papà!" dice Adele con orgoglio, mentre la massa atterra con uno schianto.

“That’s my pop!” says Adele proudly, as the mass lands with a crash.

Un uomo la aiuta a scalare la recinzione.

A man helps her climb the fence.

Mentre si arrampica sulla cima della recinzione, vediamo grandi cumuli scuri di carbone e un carro merci pieno, dove figure piegate afferrano pezzi da lanciare dall'altra parte. C'è anche Cesarina.

As she scrambles over the top of the fence, we see great dark heaps of coal and a full freight car, where bent figures grab pieces to toss to the other side. There’s Cesarina, too.

Mentre Adele penzola dalla cima del recinto, con la camicetta strappata, Raoul chiede: "Vuoi una mano?"

"No! Vattene!"

Lui si avvicina comunque e la guarda allegramente mentre lotta.

As Adele dangles from the top of the fence, with her blouse ripped, Raoul asks, “Want a hand?”

“No! Go away!”

He comes over anyway and gleefully watches her struggle.

Alla fine lei chiama: "Raoul!"

Lui la aiuta a scendere, afferrandole le gambe sotto la gonna.

At last, she calls, “Raoul!”

He helps her down, grabbing her legs under the skirt.

Quando tocca terra, lei si gira e lo schiaffeggia.

"Oh, sei matta!" – dice lui – "Prima mi mandi via, poi mi chiami, poi mi dai uno schiaffo!" Lei ride mentre lui se ne va arrabbiato.

When she gets down, she turns and slaps him.

“Oh, you’re crazy!” he says. “First you send me away, then you call me over, then you slap me!” She laughs as he walks away angrily.

Aiutando suo padre con un enorme trave di legno, Adele chiede, "Non ci sono i guardiani?"

"Stai tranquilla! Il professore sta chiacchierando con uno di loro".

Helping her father with a giant wooden beam, Adele asks, “Aren’t there watchmen?”

“Don’t worry! The Professor is chatting with one of them.”

Pautasso lancia la trave oltre la recinzione.

Pautasso tosses the beam over the fence.

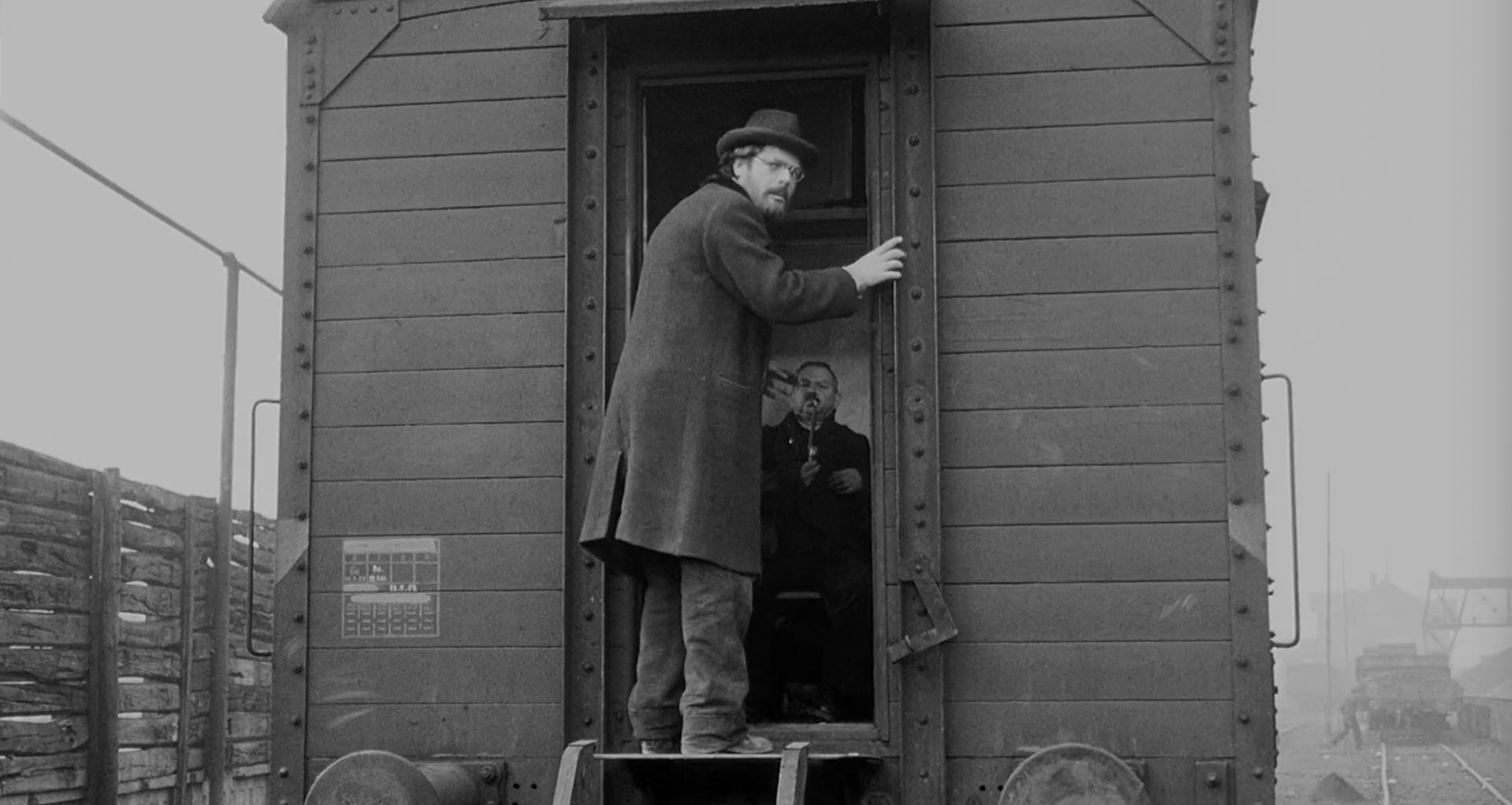

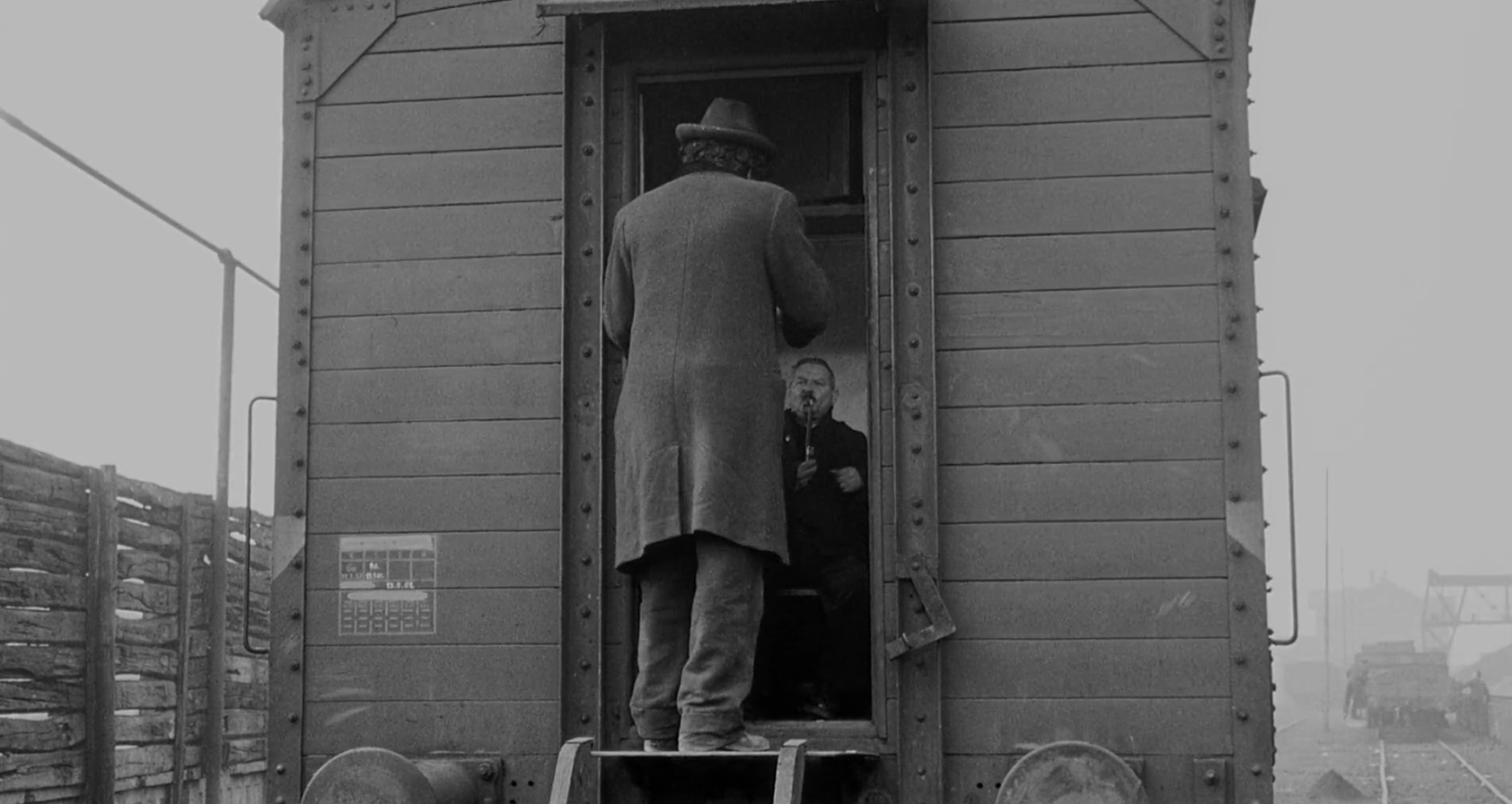

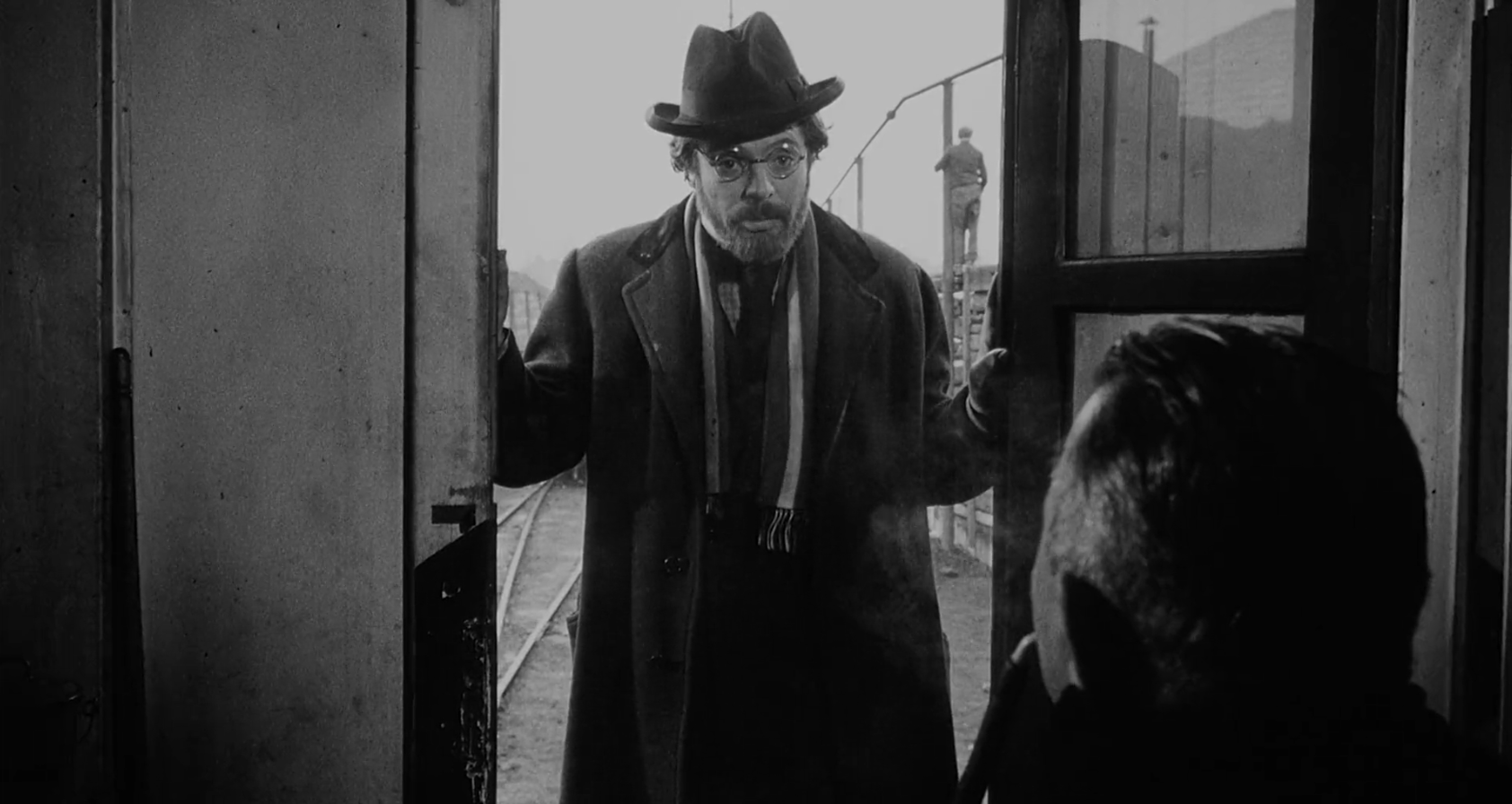

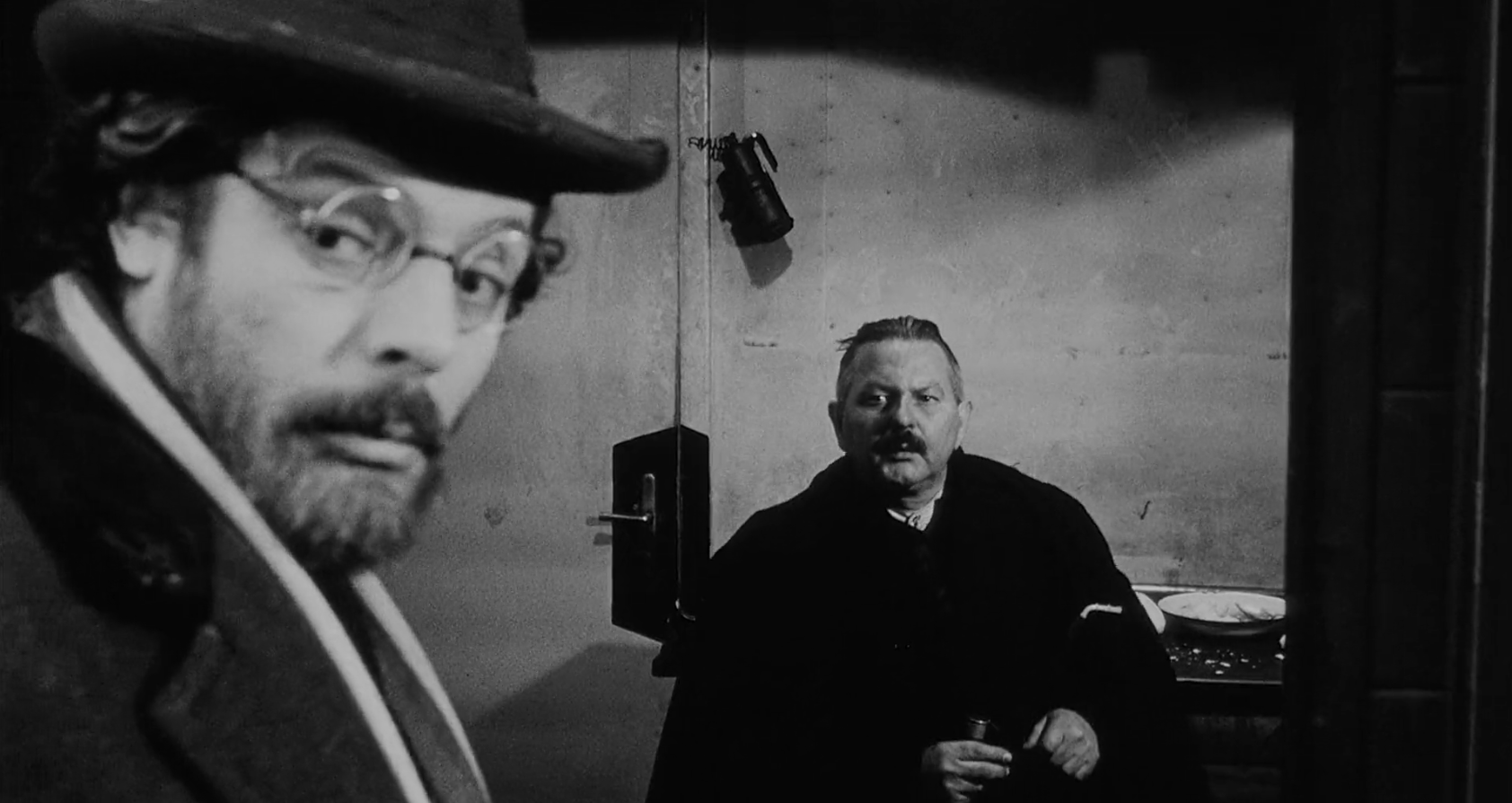

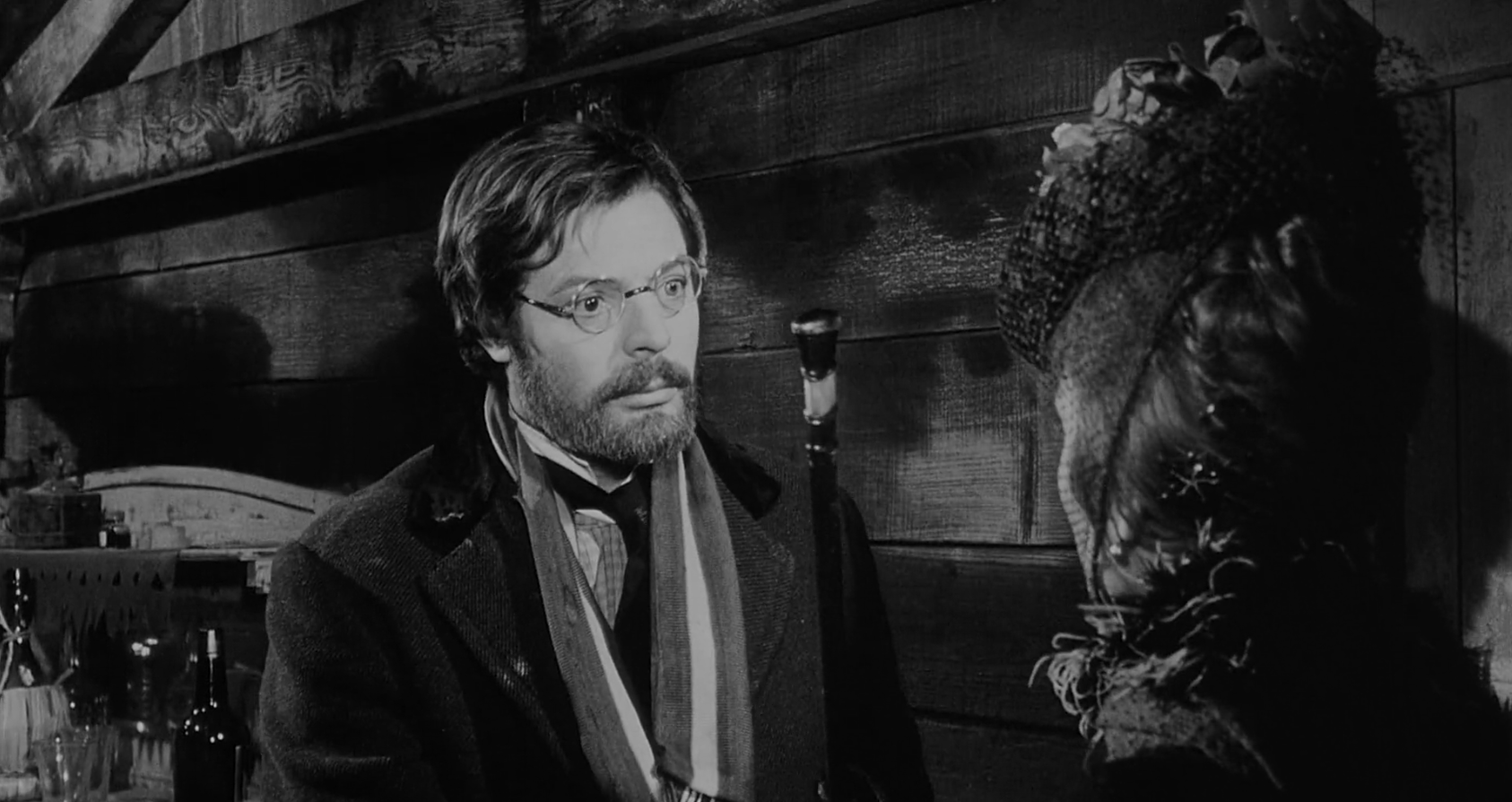

Il forte schianto della trave che atterra fa trasalire il professore, che sta sulla porta di un vagone ferroviario e consiglia pazientemente al guardiano di organizzare i suoi colleghi in un sindacato.

The loud crash as the beam lands startles the Professor, who stands at the door of a rail car, patiently advising the watchman to organize his co-workers into a union.

"Per dimostrare solidarietà con gli scioperanti bisogna scioperare!”

"To show solidarity with the strikers you have to go on strike!"

Il guardiano fa cenno al professore di spostarsi, in modo da poter sputare. Può vedere chiaramente cosa stanno facendo gli operai tessili.

The watchman gestures for the Professor to move aside, so that he can spit. He can clearly see what the textile workers are doing.

Dice al professore: "Tu professore parli per non congelarti la lingua. Sai che i ferrovieri non si possono muovere? Se scioperiamo, mandano le truppe e ci mettono in galera come disertori".

He tells the Professor, “You, Professor, speak to prevent your tongue from freezing. Do you know that railway employees can’t budge? If we strike, they send in troops and we’re jailed as deserters.”

"Allora voi ferrovieri state lì a guardare?"

"Ti sbagli. Non guardiamo niente" – fa notare lui – "Infatti i tuoi compagni stanno rubando il carbone, e io non li vedo".

“So you railway employees just sit there and watch?”

“You’re wrong. No one is watching anything,” he points out. “Your friends are stealing coal, and I don’t see them.”

Fuori dalla caserma dell’esercito si è formata una fila. Davanti, un soldato versa la zuppa nella pentola di latta che ognuno ha portato. Affamate, le persone cominciano a mangiare mentre si allontanano.

Outside the military barracks, a line has formed. At the front, a soldier pours soup into the tin pot that each has brought. Hungry, the people start eating as they walk away.

Un ufficiale appare e spinge il soldato da parte. "Siamo in un ristorante? Andatevene!" Afferra la pentola più vicina e non la lascia andare, anche se la donna – Bianca, la sorella di Omero – lotta con lui.

An officer appears and pushes the soldier aside. “Are we a restaurant? Get out of here!” He grabs the nearest pot and won’t let go, although the woman – Bianca, Omero’s sister – struggles with him.

Agli ordini dell'ufficiale, i soldati spingono via la folla e chiudono il cancello.

At the officer’s orders, soldiers push the crowd away and slam shut the gate.

Fuori, la folla batte sul cancello, gridando. Alla fine si dirigono verso casa, abbattuti.

Outside, the crowd pounds on the gate, shouting. At last, they head home, downcast.

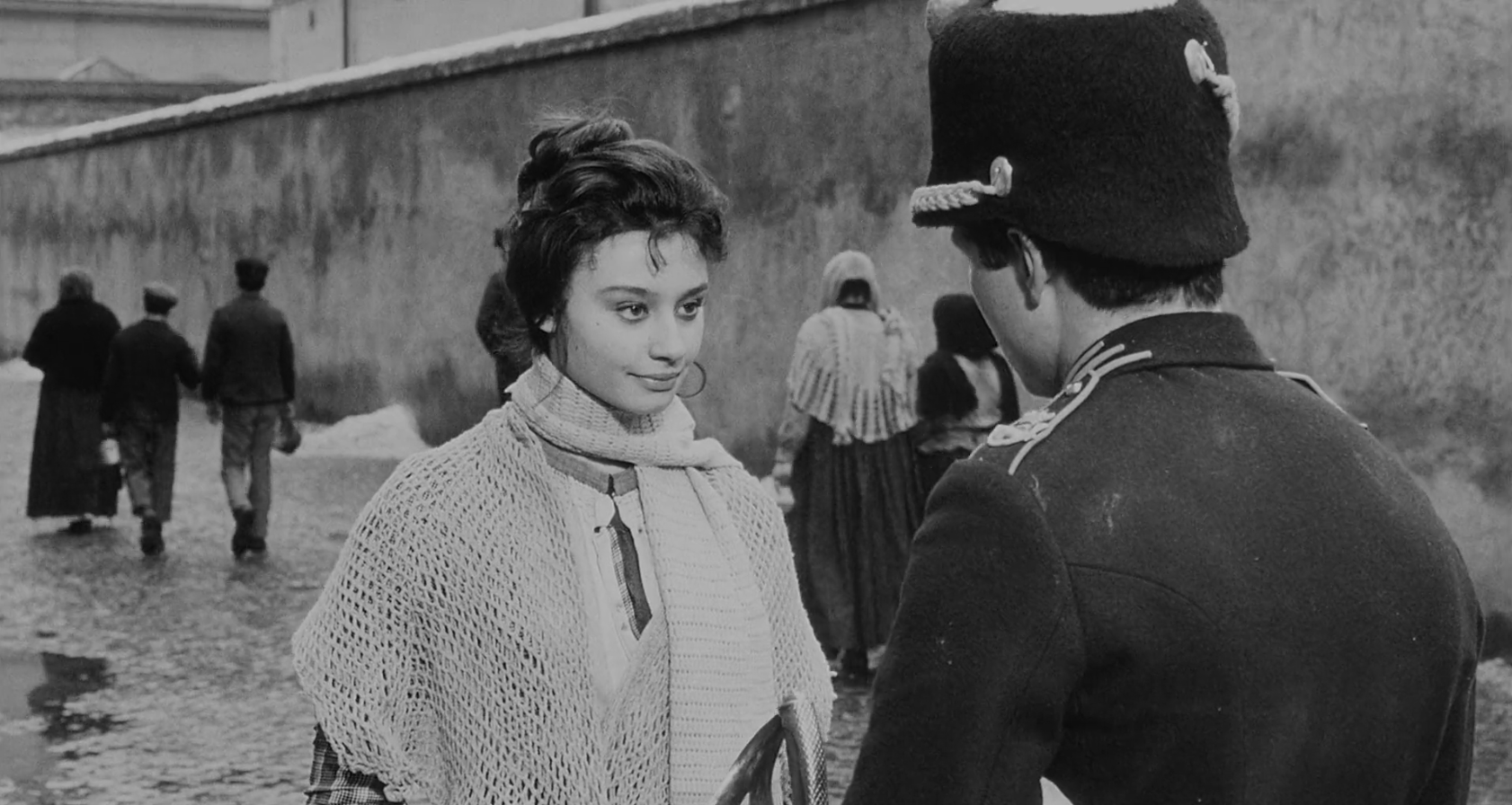

Vediamo Bianca allontanarsi, senza la sua pentola. Dietro di lei il cancello si apre e un soldato (Enzo Casini) corre per raggiungerla.

We see Bianca walk away, without her bowl. Behind her the gate opens, and a soldier runs to catch up with her.

Lei si gira quando lui la chiama a bassa voce: "Ehi, signorina!"

She turns around when he calls her quietly, “Hey, Miss!”

Mentre sono uno di fronte all’altra, una musica dolce suona da fuori campo. Lui è molto giovane, una pentola piena in una mano e una spada nell'altra.

"Mi ha mandato il caporale e questa è la tua zuppa. È dentro la tua pentola".

As they face each other, sweet music plays from off-screen. He’s very young, a full pot in one hand and a sword in the other.

“The corporal sent me. And this is your soup. It’s in your pot.”

"Meno male!" dice lei.

"E anche questa pagnotta". Lei gliela estrae da sotto il braccio.

"Grazie!"

“Thank God!” she says.

“And this bread too.” She pulls it from under his arm.

“Thank you!”

Un mestolo versa la zuppa in una scodella, mentre delle mani la prendono – le mani del soldato, Antonio. Siede a tavola a casa di Omero e Bianca e le passa la zuppa.

A ladle pours soup into a bowl, as hands reach out for it – the hands of the soldier, Antonio. He sits at the table at Omero and Bianca’s house and passes the soup to her.

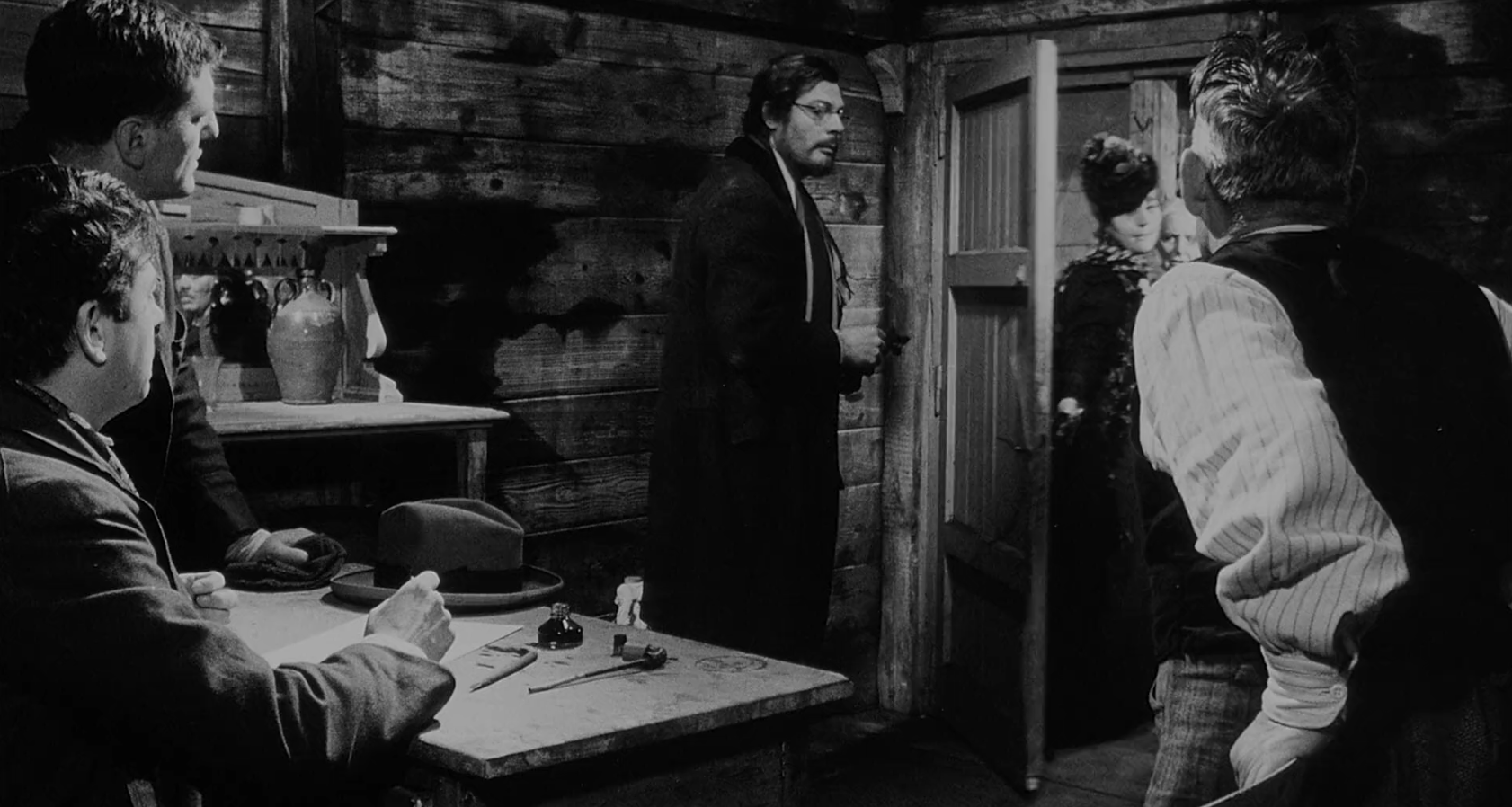

A casa di Giulio, gli operai stanno discutendo le loro richieste ai padroni, che hanno chiesto un incontro.

"Per prima cosa: un turno di tredici ore con un'ora per il pranzo" – dice il professore – "Secondo: revocare l'azione disciplinare contro Pautasso. Terzo: revocare le multe inflitte agli operai". E continua con molte altre richieste.

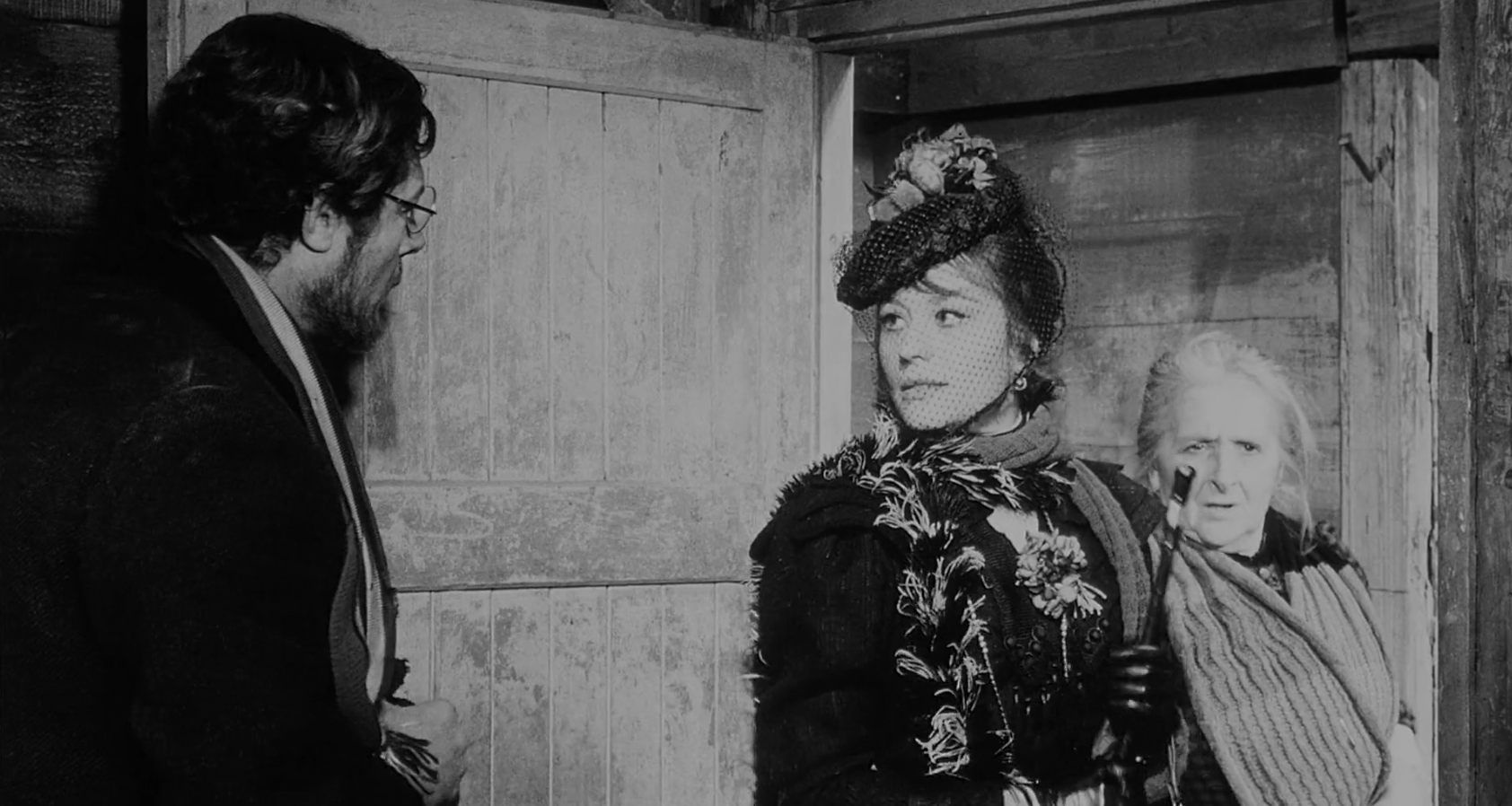

I membri del comitato si sono vestiti bene per la riunione. Cesarina indossa il suo abito della domenica e il suo cappello. Giulio si pettina con cura.

At Giuio’s place, the workers are discussing their demands to the bosses, who have asked for a meeting.

“First: a thirteen-hour shift with an hour for lunch,” says the Professor. “Second: repeal the disciplinary action against Pautasso. Third: repeal the fines imposed on the workers.” He goes on with many more demands.

Committee members have dressed up for the meeting. Cesarina is wearing her Sunday dress and hat. Giulio combs his hair with care.

Gli scioperanti temono di chiedere troppo, quindi l'insegnante, che sta prendendo appunti, li incoraggia.

The strikers worry they are asking for too much, so the schoolteacher, who is taking notes, encourages them.

Il gruppo si volta per un'improvvisa interruzione: "Cosa?!" – urla una donna – "Secondo te dovrei venire qui in segreto per non dare fastidio a quel cretino di mio padre?"

Giulio corre fuori dalla stanza. Sentiamo la sua voce arrabbiata: "Lo dico per l'ultima volta, non devi più entrare in casa mia!"

The group looks over at a sudden interruption: “What?!” a woman yells. “You think I should come here in secret to avoid upsetting my blockhead of a father?”

Giulio runs out of the room. We hear his angry voice: “I’m telling you for the last time, don’t ever set foot in my house again!”

Corre di nuovo dentro e sbatte la porta, con i capelli ora scompigliati. Allora sua figlia, Niobe (Annie Girardot), entra chiedendo: "Chi credi di essere? Me ne sbatto”. È vestita elegantemente, con cappello, velo e sciarpa.

He runs back inside and slams the door, his hair now disarranged. Then his daughter, Niobe, enters asking, “Who do you think you are? I don't give a shit.” She is elegantly dressed, in hat, veil, and scarf.

"Anche se tu morissi, io me ne sbatterei. É per la mamma che sono venuta, non per te.” Aggiunge: "Visto che ti vergogni tanto di me, sissignore, faccio la vita* e vado con chi mi paga. E chi mi vuole mi può trovare al Caffè Corsini".

*Questo è un modo per dire che è una prostituta.

“Even if you can dropped dead, I wouldn’t give a shit. I came to see Mama, not you.” She adds, “Since you’re so ashamed of me, yes sir, I’m in the life* and I go with anyone who pays. And whoever wants me can find me at the Caffè Corsini.”

*In Italian, this phrase is a way of saying that she’s a prostitute.

Lei fa cadere l'ombrello e il professore lo raccoglie. I loro occhi si incontrano.

She drops her umbrella, and the Professor picks it up. Their eyes meet.

"Vai via! Fuori!" grida suo padre, e lei se ne va.

“Get out of here! Out!” her father yells, and she leaves.

Imbarazzato per il suo amico, Pautasso dice: "Forse i padroni ci stanno aspettando".

"Calma, amici. Senza fretta” – dice il professore – "Fateli pure aspettare i padroni".

E il gruppo esce a testa bassa, come se stesse andando in chiesa.

Embarrassed for his friend, Pautasso says, “The bosses might be waiting for us.”

“Relax, friends. Don’t rush,” says the Professor. “Just make the bosses wait.”

And the group leaves, heads bowed, as if on their way to church.

FINE PARTE 6

Ecco the link to Parte 7 of this cineracconto! Subscribe to receive a weekly email newsletter with links to all our new posts.